Identifying Shorebirds

Across North America, there are about 50 native species of shorebirds, not including occasional rare visitors, and in Europe these birds are called “waders” because that is what they do. I first saw waders as a teenager at Spurn Point in the north of England during April 1961 when I recorded bar-tailed godwits, red knots, sanderlings, dunlins, redshanks, and a turnstone. Some of these same species or their relatives are now seen by me here in California. More about my adolescent bird watching is included my novel She Wore a Yellow Dress.

As you might expect, shorebirds populate the seashore and coastal and inland wetlands. They are represented by four families – sandpipers, plovers, oystercatchers, and avocets/stilts. Other birds that mix with shorebirds, such as waterfowl, seagulls, herons, and grebes are not part of this agenda.

The sandpiper family includes small birds (length 4.5 to 9 inches/11.5 to 23 cm) that are called sandpipers (nicknamed “peeps”), as well as many similar-sized to larger relatives, with names such as sanderling, dunlin, red knot, Wilson’s snipe, wandering tattler, dowitchers, surfbird, three species of phalarope, and ruddy and black turnstones. Wilson’s snipe and the American woodcock occupy inland marshes and forest thickets. There are also species of large sandpiper that include the long-billed curlew, whimbrel, several types of godwit, willet, and a bird with the title of yellowlegs.

Within California, a few shorebirds live year-round along the coast and on wetlands, but the population increases dramatically during fall when large numbers of shorebirds arrive or pass through on their way to wintering grounds elsewhere. They return to their northerly breeding sites in spring. The least sandpiper, the smallest shorebird in the world, and the slightly larger western sandpiper, are the common representatives here in California during fall and winter. Additionally, the Baird’s, spotted, stilt, and solitary sandpipers are regular visitors. and rarer varieties show up periodically such as the sharp-tailed sandpiper, buff-breasted, Terek, and upland varieties.

Most shorebirds arrive from mid-July to mid-November and leave for their breeding grounds during late March to mid-May. Deciding which species of sandpiper you are looking at can be difficult because many species replace their bright summer feathers with rather drab, similar-looking plumage during the fall and winter. To identify the six species of sandpiper most likely to be spotted in California, the following may help:

- Least: a streaked brown back; smudge-brown breast; yellowish legs; slightly drooped, black bill; prefers muddy habitats; flock size usually limited to dozens; length around 4.5 to 6 inches/11.5 to 15 cm

- Western: longish, slightly drooped black bill; dark legs; crown and upper back grayish in winter; white undersides; found on beaches, mudflats, and near lakes; migrates in large flocks of hundreds and thousands; length around 6.5 inches/16 cm

- Baird’s: slender/elegant bird; wing tips extend beyond tail; fairly short black bill; scaled gray-brown upperparts; spotted buff breast; dark legs; shuffles when feeding; travels to and from southern South America; length around 7 inches/18 cm

- Spotted: nicknamed “spotty” but breast not spotted in winter; back, wings, neck, and crown olive brown; white undersides; dull yellow legs; bill is pale yellow; white stripe on wings in flight; bobs tail up and down as it walks; widespread across North America; length 7 to 8 inches/18 to 20 cm

- Stilt: migrates to inland South America; grayish plumage on upperparts; whitish below; dusty gray breast; long yellow legs; prominent white eyebrow; dark, slightly drooped bill; prefers freshwater wetlands; length 8 to 9 inches/20 to 23 cm

- Solitary: migrates to central South America; travels alone or in small groups; prefers freshwater ponds and streams; speckled dark brown/green back; grayish breast and white underparts; olive-green legs and bill; bill is straight, thin, and of medium length; prominent white eye ring; length 7.5 to 9 inches/19 to 23 cm

Least sandpiper

Western sandpiper

Baird’s sandpiper

Spotted sandpiper

Stilt sandpiper

Solitary sandpiper

The nickname of “peep” is used by ornithologists to describe this group of small sandpipers that utter a “peeping” call. Their call is a short, thin, and often high-pitched piping cry made during flight or when the birds are running along the sand or mud.

The ubiquitous ruddy turnstone, about 8 inches/20 cm in length, also belongs to the sandpiper family though its appearance is more like a plover. It has a short, dark bill that is slightly upturned at the end. Its similar-sized relative, the black turnstone, has a much more restricted range, and only winters along the rocky shores of the Pacific Coast. Both species have a distinctive white wing pattern that can be seen in flight. In Europe, the ruddy turnstone is simply called the turnstone since its cousin is not present.

Ruddy turnstone

Black turnstone

Ruddy turnstone in flight

In Europe, small sandpipers are called stints, and during the 1960s I would often watch little stints pass through Spurn Point during the fall, following their breeding season in the Arctic. During those early years, I also spotted greenshanks and redshanks belonging to the sandpiper family but they are not common in North America. If you want to know why I became a birdwatcher, read my novel Unplanned.

Little stint on Spurn wetlands

Easier to distinguish are the larger members of the sandpiper family. They typically possess long bills, some with a slight upward curve like godwits and yellowlegs, and others with bills curved down such as the long-billed curlew and whimbrel. In the case of the willet, the bill is long and straight. One of the most challenging identifications is distinguishing between willets and the similar sized sandpiper species known as the dowitchers. Two varieties of dowitcher can be seen, the long-billed and the short-billed. Willets are heavier, have plain gray-brown plumage with no markings underneath, and display a distinctive white wing-band in flight. Dowitchers are dull gray, some spotting or barring on the side of their flanks, a white eyebrow stripe, and sometimes can be distinguished by their method of feeding – they probe in the mud with a rapid up and down motion like that of a sewing machine needle.

Willet in the front, short-billed dowitcher behind

There is also the Wilson’s snipe, a member of the sandpiper family and the only species of snipe native to North America. It is typically a winter visitor in California, although a few do hang around the Central Valley for summer. They are secretive and coy shorebirds that use their coloring for camouflage. When flushed, they appear using a very rapid zigzag flight and utter a harsh cry.

Wilson’s snipe

Identification of shorebirds is further complicated by the plover family whose members can superficially look like sandpipers in winter, and forage in the same habitats. They are plump-breasted birds, about 6 to 12 inches/15 to 30 cm in length, with rounded heads and short, stubby bills. They can be distinguished by the color of their bill and legs, and often have a full or partial black collar or breast band. The species commonly found on the California coast are the snowy plover, semipalmated plover, the killdeer (named after its warning cry of “kill-de kill-de), and the black-bellied plover. There are also several infrequent winter visitors to California such as the lesser sand-plover, Pacific golden plover, and piping plover.

Unlike most other shorebirds, they forage by sight. After spotting their food, they run towards it, stop, and then catch it. Most other shorebirds probe and peck in the sand or mud using the sensitive tip at the end of their bills to locate their prey.

Snowy plover

Semipalmated plover

Killdeer

Black-bellied plover, winter plumage

Shorebirds belonging to the oystercatcher and avocet/stilt families are the least difficult to identify, as illustrated below. There are two species of oystercatcher in North America, both around 16 to 18 inches in length (40.5 to 45.5 cm). The American oystercatcher has black and white plumage and a distinctive long, bright orange bill, and is found on the Atlantic and Gulf coasts, as well as along the shores of the Pacific. The black oystercatcher is found only along the Pacific coast, and both species are mainly permanent residents. In the UK, I would occasionally spot the European oystercatcher that is a separate species and has black and white plumage similar to the American oystercatcher.

American oystercatcher

Black oystercatcher

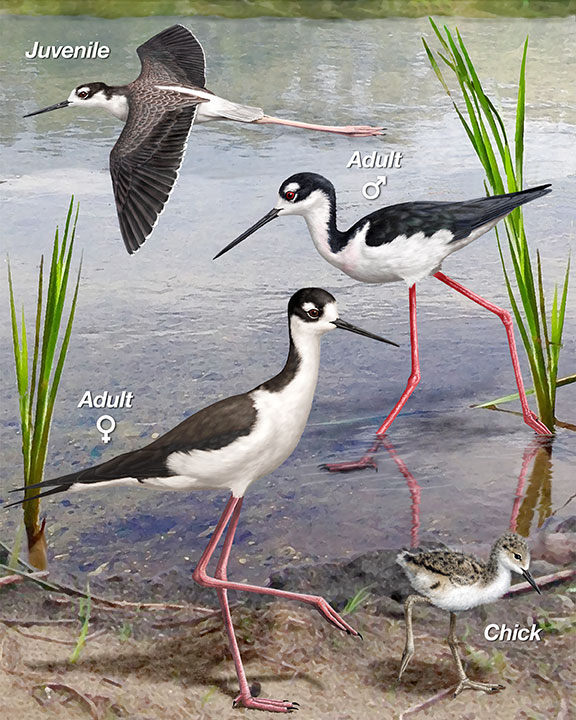

Finally, with regard to the avocet/stilt family, the American avocet and black-necked stilt are its representatives in North America.

American avocet winter plumage

My earliest effort with this bird family was to try and spot a European “pied” avocet during a visit to Minsmere Nature Reserve on the east coast of England during 1968. Unfortunately it was a failure, as I describe in Chapter 22 of my novel She Wore a Yellow Dress. At the time, the species had just returned to Britain after 100 years of absence, attracted by new habitat created through the intentional flooding of the shoreline that occurred during World War Two to defend Britain against a possible German attack. It is now well-established in Britain and has become the symbol of conservation success, being used as the emblem for the British Society for the Protection of Birds.

Black-necked stilt

Unfortunately, it would take too long to describe every species of shorebird in North America and Europe, and how to identify each one. Instead, I will provide a general guide for identifying shorebirds, and will end the paper by introducing you to my favorite of all shorebirds, the black-necked stilt.

First, let me digress and feature the marbled and the bar-tailed godwits, two species of large sandpiper that are fairly easy to identify. They have a long, slightly upturned bill and long pointed wings that enable them to migrate non-stop thousands of miles each year. They are named after the call they make.

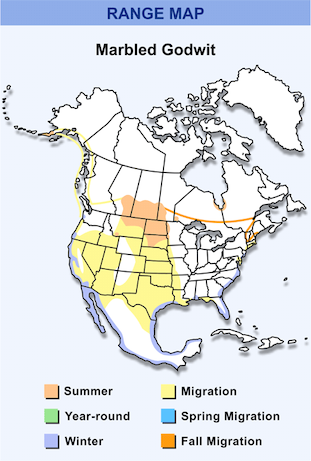

Marbled godwits are regular visitors to California in winter, arriving after breeding on the Great Plains. They are medium-sized and often can be seen congregating in small flocks on coastal mudflats and along estuaries. Some will continue onwards as far south as Mexico and the Caribbean. They can be identified by their mottled cinnamon and black coloring on their upper parts, and the rusty cinnamon plumage that is displayed during flight. They look a little like whimbrels but extend their feet beyond their tail feathers during flight.

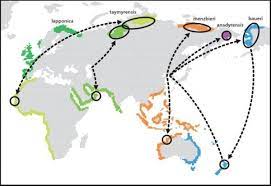

It is this species’ cousin, the bar-tailed godwit that holds the record for the longest non-stop flight of any bird. A few years ago, several of these birds were tracked traveling from New Zealand to the Yellow Sea, making the unbroken journey in nine days, a distance of 6,800 miles (11,000 km). They then carried on to Alaska. Others have been tracked flying from Alaska to southern Australia, a distance of 6,900 miles, in ten days. Although breeding in Alaska, the bar-tailed godwit typically crosses the Pacific for the winter rather than traveling south down the West Coast of the Pacific. Thus they are only rare vagrants in California, with most sightings in the north of the state.

In Europe, the species breed in the Scandinavian Arctic and Siberia, and hundreds of thousands pass through the UK on their way south, with an estimated 40,000 stopping to winter in Britain, especially along river estuaries such as the Thames, Humber, Dee, and Forth. As I mentioned earlier, I was fortunate to see this bird traveling past Spurn Point.

North American marbled godwit

Marbled godwit – Migration map

Bar-tailed godwit – Alaska/Eurasia

Bar-tailed godwit – Migration map

Godwits are an example of how size, physical features and call help with a bird’s identification, but this often does not help with smaller shorebirds, especially during non-breeding.

For example, the dunlin, a medium-sized, chunky sandpiper, with a length of about 8.5 inches/22 cm and slightly smaller than an American robin, has a distinctive black belly and a vivid mottled rusty back during spring and summer, but for the rest of the year it molts into a mousy gray-brown and the black stomach patch disappears. In profile, it is round-backed and hunched, has a medium-length drooped bill, and forages using its bill like the needle of a sewing machine (similar to dowitchers).

Dunlin – spring/summer plumage

Dunlin in winter

You will find recording bill length and curvature to be very helpful for many shorebirds, and leg color will also helps identify some species. For example, greater and lesser yellowlegs have long legs that are colored bright yellow, oystercatchers possess pale pink legs, and avocets stand on long, spindly blue/gray ones.

If you see the bird in flight, try to see if it has any form of white wing stripe like a willet, turnstone, sanderling, or oystercatcher. Similarly, some species exhibit a white rump.

Another important method is noting the bird’s behavior. How does it feed? Does it run and grab its food like a plover, walk steadily and keep its head down like small sandpipers, or rapidly peck in the mud as if its bill is a sewing machine needle like dowitchers and dunlins? Flocks of sanderling forage on the beach rather than mudflats, and they can be seen chasing the waves backwards and forwards to find food within the narrow inter-tidal band.

Sanderlings

Bird calls are also distinctive. Does the bird whistle like a plover, oystercatcher, or dowitcher, or do they call loudly like a yellowlegs? Maybe it chips and peeps like many small sandpipers?

Finally, look at the habitat in which you see the bird. Oystercatchers, turnstones, tattlers, and surfbirds prefer intertidal rocky seashores. Others, like sanderlings and some plovers prefer the beach. Several types of plover, such as the killdeer, forage in grassy areas, whereas many sandpipers rely on intertidal mudflats, estuaries, and pond edges; several species choose to forage in shallow water like avocets, dowitchers, and yellowlegs, and salt-loving phalaropes spend time at sea or on saltwater lakes such as Mono Lake in California.

These ways of differentiating may seem complex, but if you study a bird carefully you can usually come up with a satisfactory identification. Consider using the checklist below:

Shorebirds Identification Guide

- Size, shape, and general appearance

- Single bird, or in small groups, or in flocks

- Plumage color pattern, including wing stripes/white rump

- Size, shape, color of bill

- Length and color of legs

- Behavior while feeding and in flight

- Bird call

- Habitat in which foraging

- When and where it was seen

Now let me shift to the black-necked stilt to illustrate how the above guide can work. It is a species named after its black and white plumage and the long, thin, pale pink legs. Also, it is the only stilt native to North America, and became a favorite of mine because there is nothing like it in the UK. It is small, about 14 inches/36 cm in length, has an unusually long neck for a shorebird, and walks slowly and deliberately as it forages for food. Its bill is black and needle-like, and its call is a distinctive and loud “yap” or “keek”, often given in a series when alarmed. The species is fairly abundant in wetlands and coastal areas of California, and using the above guide, I would summarize the stilts I see on the Corte Madera Creek as follows:

Black-necked stilt

- Tall and lanky with delicate-looking body and long neck

- Seen in small groups or pairs

- White below, black wings and back; black extends from back along the neck to end as a black cap covering the head from just below the eye; tail feathers white with some gray banding

- Long, needle-like bill

- Long, rosy pink legs

- Wanders/pecks at food at edge of the mud close to the water/also occasionally sweeps bill through water, and in flight, pink legs are stretched behind its body; it usually flies low over the water

- Produces a noisy, sharp “yap”; high-pitched and the call is repeated

- Seen on mud flats and at the water’s edge in tidal areas

- Seen all the year round in northern California wetlands

Black-necked stilts at Corte Madera Creek, CA

Since the mid-1960s, the global population of black-necked stilts has remained fairly constant, although in California the numbers have been impacted by a substantial loss of natural wetlands. Of the stilts that breed in California, 70 percent nest in the Sacramento Valley.

Black-necked stilts are their most noisy during the breeding season and adopt different methods to frighten away potential predators. One is known as the “popcorn display” where several adults circle a potential predator, and jump, hop, and flap their wings, calling loudly to frighten the threat away. There is also the “false incubation” when the adult crouches as if incubating eggs and then moves on to another spot to repeat the process. Finally there is the “broken wing” distraction when the bird feigns injury to persuade the predator to follow it.

Most definitely, the black-necked stilt is my bird of the month.

Shorebirds in general have managed to preserve robust populations, in part because so many breed on the northern Arctic tundra. However, that appears to be under threat because of habitat deterioration and increased nest predation. Climate change is interfering with food and nest availability, such as early summer cold spells, and shifts in animal population is causing a higher proportion of egg and chick losses. More research needs to be done to develop appropriate conservation actions.

I have a bird that has confused some experts. I live in Australia and I believe it may be a vagrant from North America but am not really sure. I would like to upload the photo for identification.