The “Booming” Bittern

North American Bittern, Petaluma, CA May 2025

Photo Credit – Author

The first North American Bittern I ever saw was a few weeks ago at Shollenberger Park in Petaluma. This solitary bird was stealthily hunting its prey. It stood motionless alongside the tall grasses at the edge of the wetland, waiting for its quarry to appear. My excitement grew as I realized it was a new species, and it showed no signs of leaving. It’s not every day you spot a variety of birds for the first time. It was not “booming” as male North American Bitterns do during their breeding season from March to May, especially at dawn and dusk. They use their windpipe muscle cords and transform their gullet into an echo chamber to produce a call like a foghorn. It’s a unique bird call.

Bitterns are waders belonging to the heron family. They primarily forage for fish but also consume frogs, aquatic insects, salamanders, water snakes, crayfish, and small rodents. Their name originates from the French word “butor”, meaning bittern, and its Latin name, Botaurus, adds the word “taurus” because ornithologists at the time considered the bird’s call to sound like a bellowing bull.

Eurasian or Great Bittern

Photo Credit – Birdfact

There are three other species of large bitterns: the Great or Eurasian Bittern, found in Eurasia and Africa; the Pinnated or South American Bittern, found in Central and South America; and the Australasian Bittern, found in parts of Australia, New Zealand and New Caledonia. The Eurasian Bittern differs from the North American one by being slightly larger and having brown plumage that is vertically barred rather than speckled. The Australasian variety exhibits a more strongly patterned plumage, and cryptic patterning is characteristic of the Pinnated Bittern.

All large bitterns have brown plumage, with buff and black markings and some white. They camouflage themselves into their environment and are typically heard rather than seen. When a predator approaches, the bird freezes and stretches its neck and bill upwards to disguise its presence among the tall vegetation. Nests are built by the female, typically floating in shallow water or on the ground, and she incubates the eggs and tends to the young. The male defends the territory using his “booming” calls and may mate with two or three females. Bitterns have a lifespan estimated by some to be about four years.

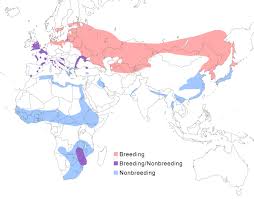

Eurasian/Great Bittern Range

Photo Credit – HeronConservation

North American Bittern Range

Photo Credit – HeronConservation

The breeding range of the Eurasian Bittern extends across Europe, Asia, and the northern coast of Africa, with occasional sightings south of the Sahara. A subspecies is endemic to southern Africa. The North American Bittern breeds in south-east Alaska and Washington, across Canada, and south through the United States as far as California in the west and Ohio, Pennsylvania and West Virginia in the east. The South American Bittern’s territory ranges from southern Mexico to northern Argentina. Like their North American cousins, all large bitterns “boom” during the breeding season.

Above are “booming” bitterns, courtesy of the UK Royal Society for the Protection of Birds.

Some North American and Eurasian Bitterns are long-distance migrants, although those breeding in warm climates, such as California, may be permanent residents. In North America, migrants spend their winters in the southern United States and along the Gulf Coast. In Eurasia, most birds migrate to Africa, the Middle East, India and South China. They typically travel at night singly or in small flocks. By contrast, Australasian Bitterns are usually sedentary, and there is little evidence of migratory movement among South American Bitterns.

Estimating populations for bitterns is challenging due to the nature of their habitat and secretive behavior. Reports suggest their numbers are declining due to the loss and degradation of wetlands. Organizations usually calculate their numbers by counting “booming” males, due to the birds’ secretive habits. The “boom” may be heard up to three miles away. Evidence suggests that climate change, such as increased evaporation demand due to higher temperatures, is also affecting the number of North American Bitterns. Even so, their numbers are large enough to keep them off the “threatened” list.

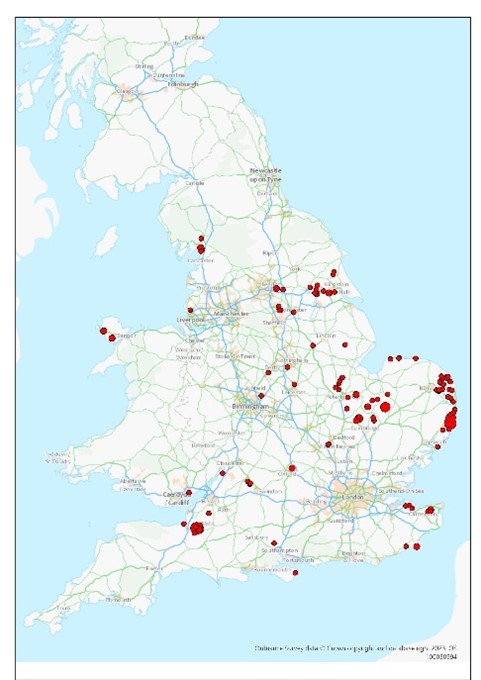

Eurasian Bittern presence in the UK during 2023

Photo Credit – The RSPB Community

The conservation situation involving the Eurasian Bittern in the UK is different. After becoming extinct in the late 1800s, these birds began to return in the 1950s, taking advantage of the flooding in the Norfolk Broads during World War II, which was caused by the need to defend against a potential German invasion. Its numbers again declined in the late 1900s. Unfortunately, I never saw one in my native Yorkshire during my bird-watching years of the 1950s and 1960s.

The 2024 annual “booming” count of males in the UK places the total number of males at 283, with a broadening distribution across England and Wales. Hopefully, numbers will continue to rise. The British Trust for Ornithology places the species on the Amber List of UK Birds of Conservation Concern.

So far, I have presented information on the larger-sized bitterns. However, there are several species of smaller bitterns. These birds go by various names, typically inhabit freshwater habitats, blend in with their surroundings, climb rather than walk among the reeds, and freeze in place at the hint of danger. They do not “boom”. Their calls range from a clicking sound to a low-frequency barking or croaking noise.

Least Bittern

Photo Credit – Cornell Lab of Ornithology

In North America, the representative is the tiny Least Bittern. They are only slightly larger than a Red-winged Blackbird, and they have a buff underpart, a white throat, and yellow-brown on the sides of the neck. They breed in low-lying areas from southeastern Canada through the eastern and central United States to Mexico and Costa Rica. There are also a few residents on the West Coast. In California, the species breeds in the marshes of the Central Valley and southern areas of the State. Birds move south in winter to the coastal slopes of southern California and the Salton Sea, but I have yet to see one.

In Eurasia and Africa, birdwatchers name the small bittern as the Little Bittern, but the species is a scarce spring migrant to the UK. There have been a handful of breeding attempts, for example, in Somerset and South Yorkshire, but the bird remains a rare vagrant. In South America, the Stripe-backed Bittern represents the small bitterns. In Australia, they are known as Australian Little Bitterns, whereas in sub-Saharan Africa, they are referred to as Dwarf Bitterns. New Zealand used to have a population of New Zealand Little Bitterns (known as Kaorik in Māori), but the last recorded sighting was in the 1890s. Other small bitterns are present in Asia, such as the Yellow, Cinnamon, and Von Schrenck’s Bitterns.

Least Bittern Range

Photo Credit – sdakotabirds.com

In summary, bitterns are aquatic birds, but birdwatchers rarely encounter them due to their lifestyle. Preserving their breeding environment and food sources is crucial for their future. “Draining the swamp” threatens their survival, and “climate change” affects where and when they breed.

We will learn from New Zealand’s experience. Not only is the New Zealand small bittern extinct, but its Australasian Bittern population has declined to between 250 and 1000 individuals. Wetland drainage, habitat clearance, and predation were the causes. Additionally, during the 1900s, bittern feathers in New Zealand were used to make trout lures because they resembled whitebait when trailed through water. Matuku-hurepo, as bitterns were known to the Māori, also served as a food source and featured in ritual celebrations. The country has taken steps to reverse this trend.

“The Genius of the Bog” is the description given by the American writer Henry David Thoreau during the 19th century to the North American Bittern. Hopefully, these bitterns will continue to justify their nickname.

The Australasian Bittern in New Zealand

Photo Credit – theforestbridgetrust