Population Decline among Wild Birds, with Special Attention to the Eurasian Skylark and the American Bobolink

It was the summer of 1954 when my childhood hobby of birds’ egg collecting came to an end. The British government implemented the Protection of Birds Act, 1954 that forbid me to take wild birds’ eggs, and at the same time, protected adults and their nests from human interference. The United States had many years earlier, in 1918, introduced similar legislation through its Migratory Bird Treaty Act that applied to approximately 1100 species, but which excluded non-native types such as house sparrows, European starlings, and pigeons.

Where I lived, up until the mid-1950s, it was normal to go “bird nesting” and gather the eggs you found to build up your egg collection. I never thought about the consequences on bird populations. Even after it was illegal, I refused to throw away my assortment of eggs. More about my egg collecting habits can be found in my two novels Unplanned and She Wore a Yellow Dress.

With these strict new controls, you would have expected bird populations to boom, but this has not always been the case. The reasons are complicated and below I try to describe some of the important aspects of avian demographics. At the end of this paper, I illustrate the decline using the European skylark and North America bobolink.

A. Background data

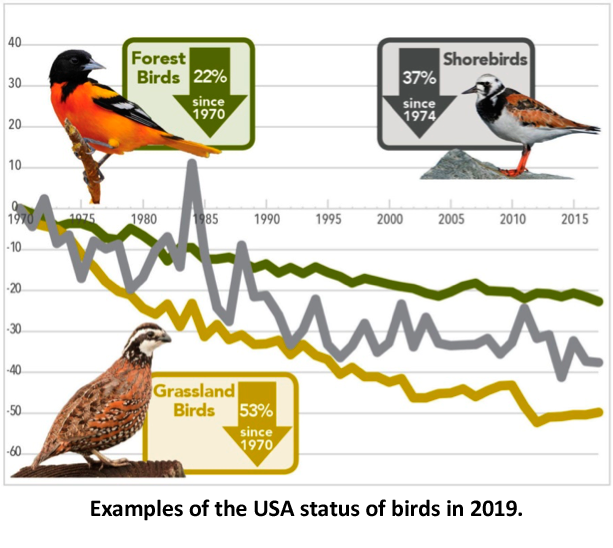

- A recent survey of 529 bird species in North America found a net decline in population of nearly 3 billion birds since 1970. Today the current bird population is 29 percent lower than it was. The impact is different by species and by the habitat they prefer, and the changes affect common species such as meadowlarks (a member of the blackbird family), horned larks, and red-winged blackbirds, as well as rarer species. There are also birds whose population has moved in the opposite direction. For example, bald eagles show a gain of 15 million birds, falcon populations have increased by a third, and there are 34 million more waterfowl (ducks and geese).

- Many birds that migrate are affected by this overall decline. Current US radar data indicates a 14 percent decrease in nocturnal spring-migration during the past decade.

- Europe is suffering from a similar situation of increases and decreases. Wintering waterfowl in the UK have more than doubled, and species such as the jackdaw, wood pigeon, great spotted woodpecker, and nuthatch show a several-fold increase. Conversely, species such as the song thrush, turtle dove, nightingale, cuckoo, swift and fieldfare show alarming declines.

- There are about 83 million pairs of birds nesting in the UK, down 19 million compared with the late 1960s, but the total bird population seems to have stayed fairly constant since the 1990s. Not included in these numbers are the estimated 6 million captive red-legged partridges and 47 million pheasants that are released annually for shoots.

- A new study released by the University of New South Wales estimates a worldwide median number of wild birds of 50 billion, or six birds for every human on the planet, but is cautious about the accuracy of its calculations. Reliable comparative historical data is missing because there has been no consistent methodology used to establish these counts. The global number of wild bird species is currently in the range of 11,000 to 18,000, and there are around 1,200 species that have fewer than 5,000 individuals worldwide.

- Avian decline is usually attributed to habitat loss (e.g. caused by new farm practices, urbanization, and drainage, etc.), the use of pesticides, hunting and killing, and climate change.

- Some species remain common and widespread, with four species qualifying for the worldwide “billion birds” club; these are the house sparrow (1.6 billion), the European starling (1.3 billion), the ring-billed gull (1.2 billion), and the barn swallow (1.1 billion).

- At the same time, several bird species are now extinct. In North America, the dusky seaside sparrow that lived on the east coast of Florida was last seen alive during the 1980s, and the Bachman’s warbler that bred in the south-east and mid-western states of the US, and wintered in Cuba, is believed to have become extinct in the second half of the 1900s.

- In Europe, the pied raven (a genetic color morph of the common raven), only found on the Faroe Islands, was last spotted during the 1940s, and in summary, since the year 1500, it is estimated about 180 bird species have become extinct worldwide .

- So why do these trends matter? The worry is what happens to nature when species that play key roles in pollination and seed dispersal or control the abundance of pests, decline or disappear. The potential effects on society are unclear.

B. The skylark and the bobolink

Two examples of bird species under serious threat are the Eurasian skylark and the American bobolink (named for its bubbling “Bob O’Lincoln” song). The species are not related. The bobolink is a member of the blackbird family and the skylark belongs to the lark group of birds; only its cousin, the horned lark, is native to North America. Both species rely on grassland and farmland, which are the habitats in North America that have suferred the greatest loss of bird population during the past 50 years, with a 53 percent decline and a reduction of half a billion birds.

Both species symbolize the countryside’s return of summer. Males deliver a bubbly, metallic song, often fluttering high above the fields, as they look for mates. Their melody has been associated with joy, freedom and enthusiasm, and has inspired poets such as Emily Dickinson, Shelley, Tennyson and Wordsworth. Both species nest on the ground, but that is where the similarities end.

Their appearance is distinctively different as the illustrations below show.

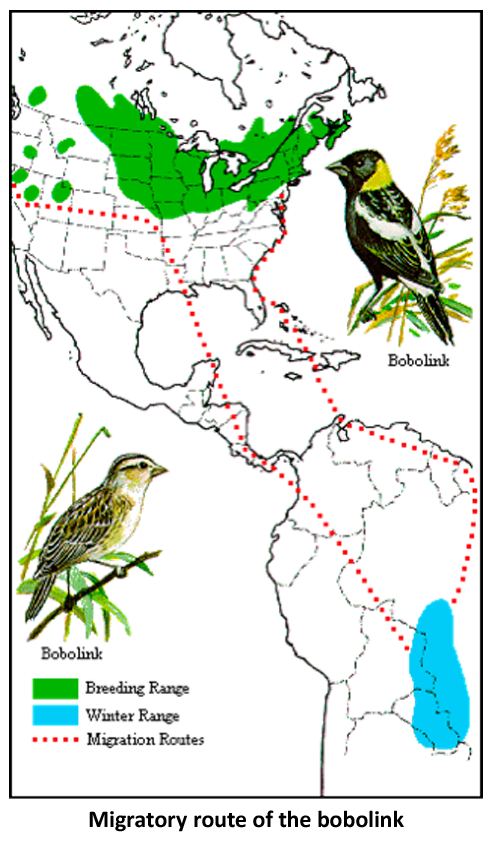

The bobolink migrates between southern Canada and the northern states to southern South America twice a year, a return journey of approximately 12,500 miles (20,000 km). In contrast, skylarks generally do not migrate. However, the two species are known to appear in each other’s territory and both are suffering serious declines in their native habitat.

Skylarks, while still common in the UK with a population of about 1.7 million, are calculated to have experienced a population decline of around 75 percent since the early 1970s. The switch in agriculture from spring to fall sown cereals has interfered with the birds’ food supply; the move from hay to silage has caused nests to be destroyed by machinery due to earlier harvesting; and on grasslands, intensified stock grazing exposes nests to trampling and makes them more accessible to predators. Efforts to reverse this trend are underway and include more organic farming, providing incentives for sowing spring crops, and implementing standards to prevent nest destruction. Indications at the present time are that these steps are stabilizing the population of skylarks

The plight of the bobolink is similar that of the skylark, with its population having declined around 65 percent since 1970. Even so, it is fairly common, with a breeding population of around eight million, of which 28 percent breed in Canada and 72 percent in the United States. Habitat destruction is the main cause for their loss of breeding territory, and it has to contend with dangerous pesticides in its wintering locations and is often treated as an agricultural pest. While on migration, it is hunted as food in places such as Jamaica.

Efforts are underway to control these interferences, with bans on dangerous pesticides, encouraging working farms to establish additional grassland, maintaining larger fields that apparently are preferred by the bobolink, and probably, most important of all, incentivizing farmers to mow hay fields outside the breeding season.