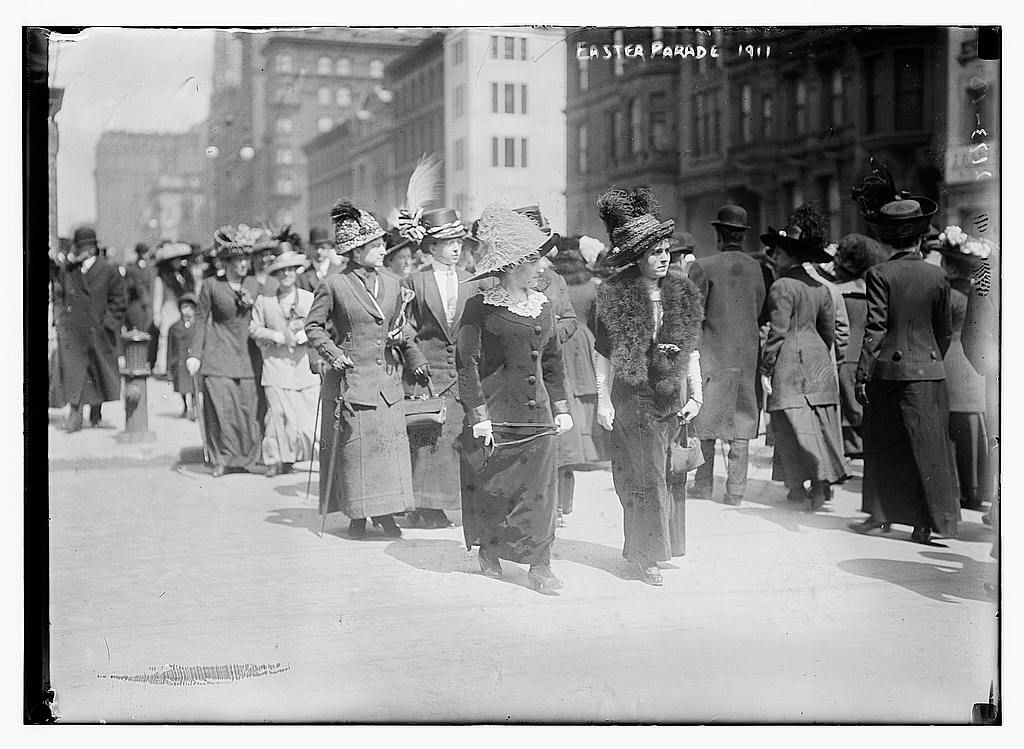

Feathers in Fashion, Easter Parade 1911 New York City

Photo Credit – Library of Congress

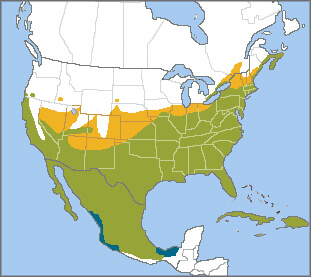

At the turn of the nineteenth century, in North America and Britain, birds were hunted for sport and food, and their feathers used for fashion. Ornithologists killed birds to examine them. Feathers made ladies’ hats, hunting supplied meat, and eggs were for consumption and collection. Birds seized included swans, geese, ducks, shorebirds, raptors, gamebirds and even small to medium-sized songbirds. Some were taxidermied and displayed in cases or kept in cages. My childhood bedroom featured a Red-backed Shrike shot and stuffed in the 1890s. The history of birdwatching was waiting to begin.

Since then, the history of birdwatching has depended on human curiosity, the arrival of optical equipment and field guides, and the impact of Artificial Intelligence.

There were exceptions to the hobby’s late beginnings. Natural History Clubs flourished earlier in the British public school system, and I had connections with one of these schools in York, England, during the 1950s. As early as 1834, the school produced a hand-written magazine called “The Ornithologist”. Schoolboys recorded their bird sightings and consolidated and published their observations. Admittedly, only the well-to-do participated.

The following paragraphs examine the history of birdwatching in Britain and North America.

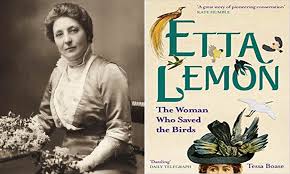

Etta Lemon, Founder Fur, Fin and Feather Folk 1889

Photo Credit – Daily Mail

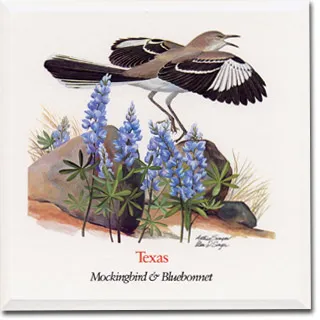

Efforts to end the feather trade and protect birds in Britain began during the late 1880s when women’s advocacy groups were formed. The Society for the Protection of Birds, SPB (first known as the Plumage League) was created in 1889 and two years later amalgamated with the Fur, Fin and Feather Folk. Queen Victoria supported its purpose and, in 1899, ordered army regiments to stop wearing osprey plumes. Osprey plumes at the time were upright millinery ornaments made from the wispy breeding plumage of the Great and Snowy Egrets and not from the Osprey. In 1904, the organization received Royal Assent and became known as the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds, and it exists today with around 1.2 million members. In 1921, the Importation of Plumage (Prohibition) Act prohibited the sale of imported plumes in Britain.

Snowy Egret

Photo Credit – US Fish and Wildlife Service

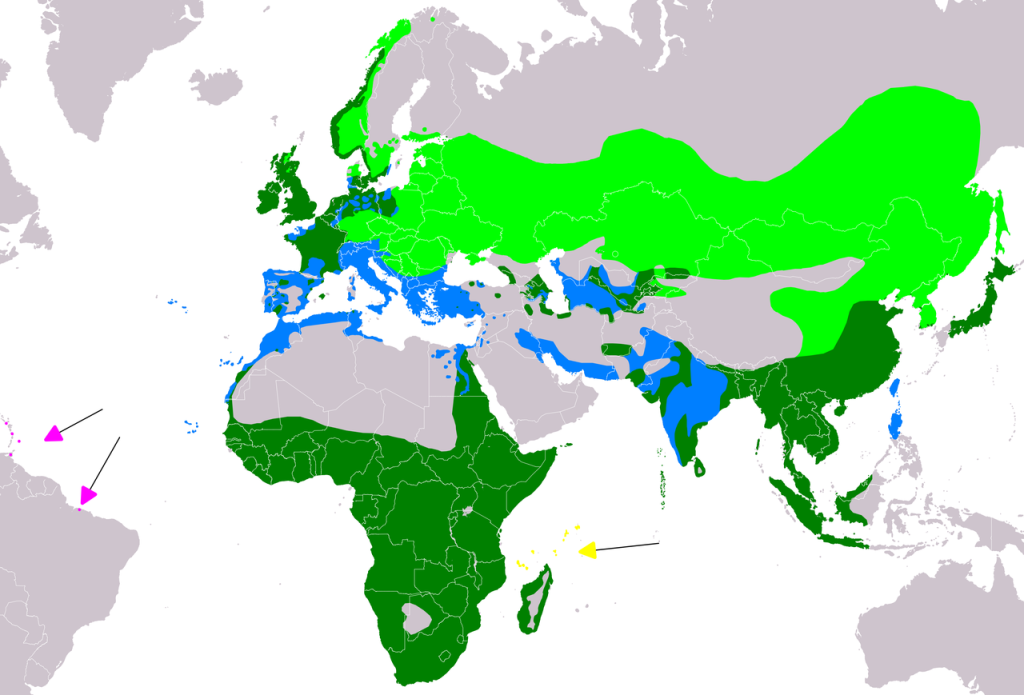

In the United States, in 1896, Harriet Hemenway and Minna Hall established the first Audubon Society in Massachusetts (named after naturalist, ornithologist and artist John James Audubon 1785-1851) with the purpose of ending the slaughter of wild birds to make women’s hats. By 1905, a national organization had formed, and persistent advocacy led, in 1913, to the Weeks-McLean Act. The law outlawed the plume trade, prohibited spring hunting of migratory birds, and banned the import of wild bird feathers. The Secretary of Agriculture was allowed to establish exemptions when specified bird species could be taken during an approved hunting season. Previously, egrets had become almost extinct, with over five million killed annually by the start of the 20th century. The general protection of all wild birds did not arrive in the United States until the 1918 Migratory Bird Treaty Act. Today, there are approximately two million members of 610 Audubon chapters.

Lapwing (aka Peewit)

Lapwing (aka Peewit)

Photo Credit – British Trust for Ornithology

UK protection for wild birds was selective, and conservation focused on breeding seasons only. One of the earliest regulations was the 1831 Game Act, applicable to grouse, pheasant and partridge, which protected these birds during specified nesting periods (the close season). The 1869 Sea Birds Preservation Act protected 35 named species of sea birds and their eggs from sports hunters during their breeding season. In 1880, a law was passed to protect annually a long list of wild bird species from April 1st to August 1st, although it did not ban the collection of eggs. An 1896 law permitted English counties to add species or specific conservation areas to the list, and a 1902 law allowed for the confiscation of stolen birds. These laws were consolidated in the 1908 Wild Birds Protection Act, which gave flexibility to administrative areas (usually counties) to add or delete protected species, outlaw specific methods of capturing birds, permit the creation of bird sanctuaries, and allow flexibility in determining the period of protection.

The UK took far longer than the United States to introduce comprehensive laws to protect all wild birds and their eggs. This did not occur until 1954, when the Protection of Birds Act was passed, ending my childhood hobby of bird nesting.

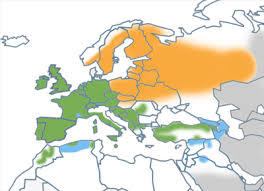

An exception to the British lack of protection was Lapwings. In 1926, Britain introduced national regulations to protect the birds and their eggs annually from March to August because the population had dramatically declined. Birds were killed for meat, and eggs were taken for sale as delicacies in nearby cities.

In 1918, the United States passed the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, which protected 1,100 species from being killed, captured, sold, traded, and transported unless the government authorized an exemption. A few non-native species, such as House Sparrows, European Starlings, and Rock Pigeons, were excluded because they had been introduced with human assistance. Protection included the birds’ eggs.

Simultaneously, Canada passed its 1918 Migratory Bird Treaty Act, which protected approximately 450 species of birds and stopped their indiscriminate slaughter. The Act prohibited taking any part of a bird, including its feathers, effectively shutting down the ornamental feather trade in Canada.

Early Carl Zeiss Binoculars

Photo Credit – allbinos.com

Out of these early beginnings around the history of birdwatching, the hobby of birdwatching has emerged. It was made possible by the advances in optics, especially the invention of Carl Zeiss’s binoculars at the start of the 20th century. These “double microscopes” removed the need to shoot birds to identify them. Ornithologists could observe them from a distance and study their behavior. They were light enough for hobbyists to carry them in the field. However, the pastime was available to a limited few. It was not until after World War 11, when binoculars became more available and Field Guides were broadly introduced, that it became an everyday recreational activity. At first, it was adopted in only developed countries, but it has since spread globally.

Quetzal in Costa Rica 2020 taken with mobile phone on scope

Photo Credit – Author

Another invention, essential to the history of birdwatching, was the telescope (spotting scope). This device appeared at about the same time as binoculars. It was heavy and less portable, and its high magnification exposed it to image disturbance when touched or knocked. This led to the invention of fixed platforms. Today’s advantage of spotting scopes is that you can attach your smartphone and take photos of what you see, as I did in Costa Rica five years ago with the Quetzal. Another option is combining a camera with a telephoto lens. This offers an opportunity to document your rare sightings and, at the same time, mix the hobbies of birdwatching and photography. Today’s scopes are much lighter and have improved low-light performance and enhanced optical performance.

Mist Net, Jerusalem 2023

Mist Net, Jerusalem 2023

Photo Credit – Author

In the 1950s, the term “twitcher” was introduced in Britain. Birdwatchers passed information about rare bird sightings, and some colleagues would instantly travel to wherever the bird was seen. It was a way of adding species to “life lists”. The nickname “a twitch” or “twitcher” came from the excitement and tension shown by some of these early bird travelers. “Chaser” is the equivalent term used in the United States.

Mist nets and trapping birds are other features of birdwatching that have developed since the 1950s. The idea of mist nets was brought to the United States from Japan in the late 1940s, where, for centuries, the technique had been used to catch small birds for local consumption and sale. Nets constructed of fine black netting strung up in sections between poles were introduced to catch birds and bats. At Spurn Point, at the start of the 1960s, I participated in mist netting to band, measure, and release birds. Records show me fitting numbered bands to species such as Redstarts, Pied Flycatchers, Whitethroats, Greenfinches, Redwings and Goldcrests. In the United States, it is estimated that over one million new birds are banded yearly, and a similar number is achieved in Britain.

The Jerusalem photo above was taken at the Jerusalem Bird Observatory, where mist netting occurs four days a week, except in spring when it is daily. In spring, 500 million birds fly over Israel, migrating back from Africa and elsewhere to their Northern Hemisphere breeding grounds.

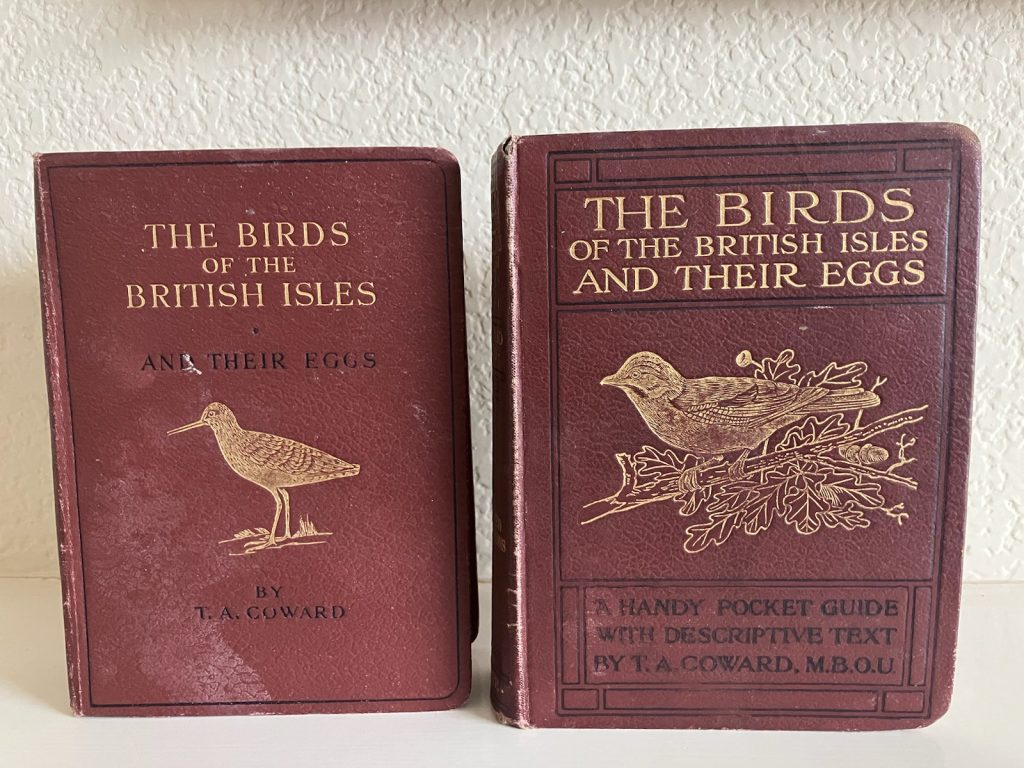

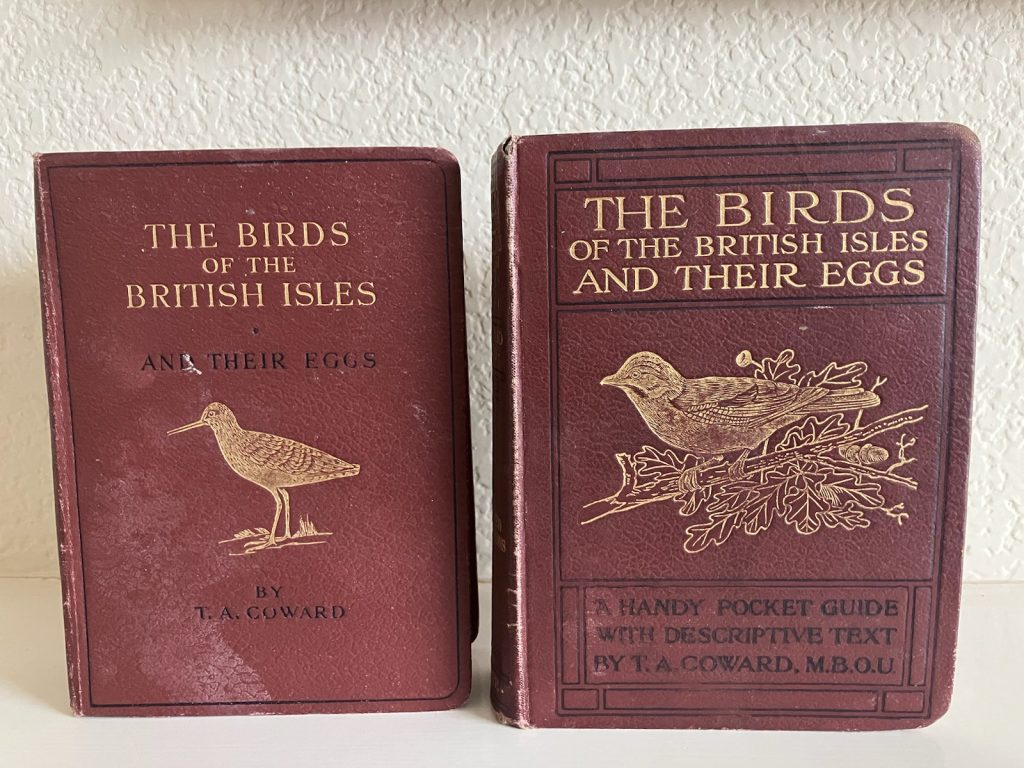

Field Bird Books 1920s

Field Bird Books 1920s

Photo Credit – Author

Another significant development in the history of birdwatching was the availability of field guides to assist birdwatchers in identifying what they saw. Field guides have been published from the early 20th century. At first, the illustrations were black and white or hand-colored with limited details for identification. As time passed, color illustrations became standard, identification features were spelt out, and range maps were provided.

My spouse’s mother used T.A. Coward’s The Birds of the British Isles and Their Eggs, published from 1920 to 1925, during her childhood birdwatching. T.A. Coward was her local ornithologist living in Cheshire, England. My field guide was the Birds of Britain and Europe (Revised 1958) by Peterson, Mountfort and Hollom, and included pages where I recorded my Life List.

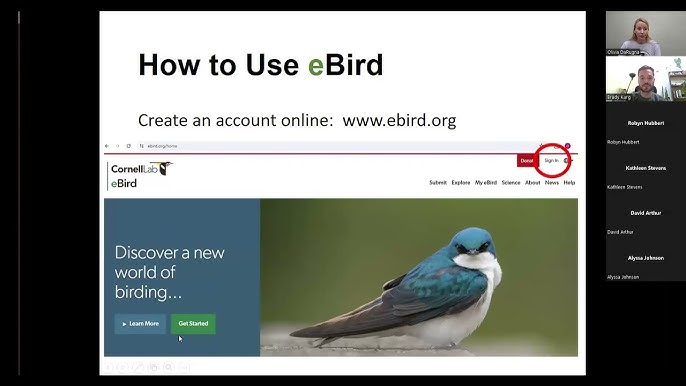

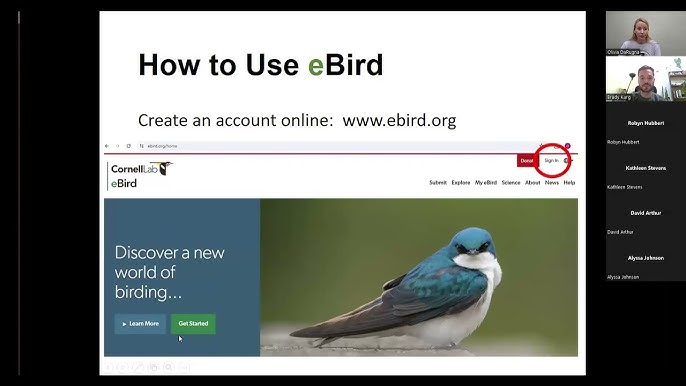

How to use eBird

Photo Credit – Cornel Lab of eBird

Identifying birds from field guides is not easy. It is hard to keep the bird in sight while you find the relevant page in your book. Identifying the bird from memory can be satisfying, but it takes time to reach that standard. That is changing today. The field guide has become an app on your mobile phone, with platforms such as eBird offering checklists of birds, their location, numbers, and dates when they are seen. The Cornell Lab of Ornithology and the National Audubon Society launched the app in 2002. Today, 85 percent of the world’s land surface is covered by eBird, from Papua New Guinea to Greenland, with over 60 million checklists and a billion observations.

This information is now provided by apps that instantly tell you what you are looking at so long as you can take a photo or audio record the bird using your smartphone. Apps include Merlin Bird ID, BirdNET, and Picture Bird in North America; and Birda, Collins British Bird Guide, Smart Bird ID (UK and Europe), Birds of Britain Pro, Warbl, and Merlin Bird ID in Britain. Some are free; some you pay for.

Rare Bird Alert, Blue Rock Thrush, San Francisco

Photo Credit – American Birding Association

Another challenge for birdwatchers has been verifying rare bird sightings. In Britain in 1959, a Rarity Records Committee (later renamed the British Birds Rarities Committee (BBRC)) was established to approve each sighting. Today, 250 species are considered “rare.” The British Trust for Ornithology maintains an internet application called Bird Track, the British equivalent of eBird. National and regional lists are updated nightly, and the site prompts birdwatchers when they must follow the BBRC process. About 85 percent of submissions are accepted.

In North America, rare bird reports usually go via eBird to the Audubon chapter responsible for the location or through some other ornithological group. They are then submitted to the North American Rare Bird Alert under the control of the American Birding Association. Non-rare bird species are listed on eBird. However, the spotter listing the observation may find themselves challenged by other eBird subscribers if the species they report are unusual or unrealistic.

Birdwatchers are also unlikely to run out of new species to spot. Global birding allows birders to travel internationally to add to their “Life List,” and with a global population of 11,145 species, it is doubtful that someone will see one of everything. Adding to this challenge is the annual addition of new species based on bird morphology and genetic advances. For example, in 2024, there was a net gain of 128 species.

New technologies continue to speed up and simplify bird identification, making birdwatching more convenient, satisfying, and participative. Here are a few examples.

- Swarovski Optik has introduced AI-powered AX Visio binoculars with a built-in camera and Merlin Bird that identifies 9,000 bird species while you are actively birdwatching.

- Live streaming birds, such as nesting albatrosses and raptors, brings birds into your living room.

- Spotting scopes continue to improve, including more light and camera attachments.

- Smartphones that identify species (including bird vocalization) are increasingly available. I use Picture Bird in North America, which offers free and subscription versions. Smartphone cameras capture photos that these applications identify.

- Camera advances include fast autofocus, shutter speeds, eye detection, and continuous shooting rates. A camera or mobile phone can be used with a spotting scope to capture evidence of the birds you saw.

- Haiku Acoustic monitors bird sounds outdoors and alerts smartphones for unusual species. An alternative is BirdWeather.

Bird Buddy

Bird Buddy

Photo Credit: Kickstarter

- Bird feeders come with cameras linked to smartphones. Bird Buddy uses AI technology to take photos, identify the species and provide alerts to your phone.

- Drones with high-resolution cameras can access remote areas to spot birds.

- Social networks and digital media provide birders with platforms to record and share sightings. Birdwatchers obtain a preview of what they might see by looking at recent inventories of birds in the location they will visit.

- AI is used to predict the presence of bird species based on environmental data and bird tracking reports using GPS tags.

California Condor

California Condor

Photo Credit – Defenders of Wildlife

- Applications exist for wind turbines to shut down when birds (especially scarce species) are spotted. An example is the protection of the California Condor.

In summary, the history of birdwatching has transformed several times over the past 120 years. Today, the hobby is soaring in popularity, with an estimated three million adults in the UK who annually go birdwatching, 96 million estimated from a 2022 survey (three out of ten adults) in the United States, most of whom are backyard birdwatchers, and eight million in Canada. The term birdwatcher is often reserved for those observing birds coming to them, whereas birder is used for people who actively and seriously search for birds.

As identification becomes more immediate and straightforward, more people will adopt the hobby. The COVID pandemic began the process. I wish you success if you are already a birdwatcher, and I encourage those who have yet to start to start. As a beginner, obtain a decent pair of binoculars and set up your identification method (smartphone recognition is probably the best). Add a reference book at home for more details and a notepad to write down what you see and where.

Birdwatching is also a social activity. Join a bird or ornithological society (county bird clubs and RSPB or British Trust for Ornithology in Britain; Audubon or American Birding Association in North America). Participate in organized bird walks, visit bird sanctuaries, and volunteer to participate in local bird population surveys. These have been conducted since the late 1960s when the pesticide DDT affected population numbers in North America. Britain’s Bird Breeding Survey also originated in the 1960s. There are also annual Garden/ Backyard Bird Counts in many countries in which to participate. May the hobby continue to thrive.

Lapwing (aka Peewit)

Lapwing (aka Peewit)

Mist Net, Jerusalem 2023

Mist Net, Jerusalem 2023 Field Bird Books 1920s

Field Bird Books 1920s

Bird Buddy

Bird Buddy California Condor

California Condor