Blue-crowned mot mot

The first resplendent quetzal I ever saw was on April 5, 1998 in the Monteverde Cloud Forest, Costa Rica. The species is considered by many to represent the most beautiful bird in the world, and although it was partially obscured by the dark forest canopy, it was sufficient to cause one of my companions to burst into tears. “It’s my wife” he said. “Her greatest ambition was to see one of these birds, but she died last year of cancer”.

I had been much more impressed by the several blue-crowned motmots we had stopped to photograph during our minibus journey from San Jose to Monteverde. However, my opinion was to change later.

This was my first dedicated overseas trip for birding although I had followed the hobby of bird watching in England during the late 1950s and 1960s. Each of the first 35 chapters of my “coming-of-age” novel She Wore a Yellow Dress is dedicated to a bird that influenced my early life, and the last chapter is given as a special tribute to my deceased wife who supported my love of birding. Only the hoopoe, from chapter nine of the book, deserves a special mention at this time, although it does not make my top ten.

22 years later, when I was back in Costa Rica, I came across a pair of quetzals during a hike I was taking along the Savegre river valley. The birds were out searching for their favorite food – wild avocados – which they swallow whole before regurgitating the pips. That magnificent sighting took them to the top of “my most beautiful birds” that I have ever seen.

A pair of quetzals in the Savegre national forest.

It also prompted the task of trying to select the top ten species of bird that I consider to be the most beautiful birds in the world, even though I may not have seen them. What follows are the results of my efforts and descriptions of the birds I have selected. I used plumage, visual presentation, and my desire to represent all 7 Continents to create this list.

Here comes number one.

1. Green-headed tanager (South America)

A striking, multi-colored songbird (with several different opalescent colors) that is endemic to the Brazilian Atlantic Forest (only about 10 percent of the original forest survives today). The species’ territory includes south-east Brazil, parts of Paraquay, and north-east Argentina. Surprisingly, the bird’s flashy coloring is used as camouflage while it forages among the forest canopy to find its diet of fruit and insects. The Portugese name for the bird is “Saira-seta-coras”, meaning seven-colored tanager.

Its breeding season is November to February in Brazil; November and December in Paraquay; and November in Argentina. Its population is unknown but the number appears stable, and although abiding in the same area most of the time, some may undertake small seasonal migrations between the forest and semi-open habitats.

2. Keel-billed toucan (Central/South America)

A species noted for its unmistakable, large, rainbow-colored bill, often considered one of the most beautiful birds in the world. Despite the bill’s appearance, it is hollow, made of keratin, with thin rods of bone for support, and therefore is not heavy. The bird’s plumage is mainly black, with a yellow neck and chest, and the bird is heard more than it is seen because of its preference for living in the tops of forest canopies; it moves between trees by hopping due to its limited flying abilities, and is found from Southern Mexico to Venezuela and Colombia; it is the national bird of Belize and the global population is estimated at up to 500,000.

3. Bee hummingbird (Cuba – North America)

This is the smallest bird in the world at 2.4 inches (6.1 cm) long, and weighs under 0.1 ounce (2.6 grams). It is found exclusively in the Cuban archipelago and is sometimes mistaken for a bumble bee since, as well as its smallness, the bird makes a buzzing noise when it flies. The male displays an iridescent red head and throat, black tips to its wings, grey-white underparts, and the remainder is bluish-green. The birds are sedentary, often living alone, but play a vital role in the ecosystem by picking up pollen on their bill and head, and passing it on as they fly from flower to flower. In a day, a bird may visit 1,500 flowers.

The species occupies the rain forest and forest edges where there are bushes and lianas. Its nest is about the size of a quarter and its eggs the size of a coffee bean. The bird has the ability to fly straight up and straight down, backwards and even upside down. Its population size is unknown, but the species is believed to be in decline.

4. Wilson’s bird-of-paradise (West Papua, Indonesia – Asia)

This species of bird-of-paradise, out of an estimated 42 types, exhibits more colors than any other bird in the family. Birds-of-paradise are extraordinary creatures, not only for the colors of their plumage, but their lacey feathers that they wear arranged into disks, flags, ribbons or wires, and that they use in dances and mating displays. In the circumstances of the Wilson’s bird-of-paradise, its teal crown is actually bare skin. The species occurs within a small range, limited to the islands of Waigeo and Batanta off the West Papua coast. Their mating ritual includes the male flashing its brilliant green fluorescent collar and calling out to the female. Supposedly, with all birds-of-paradise, the female is the one that selects her partner and chooses the one with the “sexiest” display. So long as this process continues, we can expect incredible colors and decorative feathers among this family of birds.

5. European bee-eater (Europe)

One of Europe’s most colorful birds, with an estimated breeding population of 3 to 5 million pairs. It occurs as a rare vagrant and infrequently breeds in the United Kingdom, preferring to inhabit the warmer climates of southern Europe and North Africa. Its plumage is highly distinctive with a yellow throat, rusty brown upperparts and turquoise underneath. Its diet makes it unique. As the name suggests, bees are its preferred food, although it will take butterflies, dragonflies, flying ants, and even wasps. To avoid being stung by its prey it will return to its perch and repeatedly thrash the insect against a branch to release the sting. It may catch up to 250 bees a day.

6. Grey-crowned crane (Africa)

You are more likely to see this species in a zoo than out in the wild. Its size and form, as well as its plumage, qualify it for a place on my list of most beautiful birds. Today, there are about 30,000 grey-crowned cranes living in the wild. Their usual territory is wetland/grassland in eastern and southern Africa, especially in Kenya, Uganda (where it is the national bird), Zambia and South Africa. These majestic long-legged birds stand 3.3 feet (100cm) tall, have grey bodies, white wings with brown and gold feathers, white cheeks, and a bright red inflatable throat pouch beneath their chin. The most striking feature is a spray of stiff golden feathers forming a crown around their heads. They are non-migratory, although some may move short distances.

They are famous for their elaborate mating display that includes dancing, bowing, running and jumping, while raising their wings and inflating their red throat sacks.

15 species of crane exist worldwide, including the sandhill and whooping cranes in North America, and the common and demoiselle in Europe. Do not confuse cranes with storks. Storks are not closely related, do not vocalize like cranes and are more heavily built, especially in the bill.

7. Bullock’s oriole (North America)

This songbird occupies the west of the United States, whereas a close relative, known as the Baltimore oriole, is the equivalent in the east of the country, and up until 1975, the two species were combined into one, called the Northern oriole. The adult male is medium-sized and has bright orange underparts, a black back, large white wing patches, and a black throat and black line through the eye. They are nimble and highly active birds, searching for caterpillars, and feeding on nectar and fruit. They breed on the western side of North America from southern British Columbia into north Mexico, and winter as far south as Central America. On the Great Plains, their range overlaps with the Baltimore oriole and the two species occasionally hybridize. Both male and female Bullock’s orioles sing, the male more sweetly and the female often more prolifically. A special trait is there determination to resist interference from the brown-headed cowbird that tries to use them as host parents. They are one of the very few species that will puncture and eject brown-headed cowbirds’ eggs laid in their nests.

8. Golden pheasant (China – Asia)

A delightful, timid and beautiful gamebird, native to the forests and mountains of western and central China. Additionally, it has a substantial feral population elsewhere in the world, with birds having been relocated to North America, South America, Europe, Australia and New Zealand. Two thirds of the bird’s length is accounted for by its golden-brown tail, and it sports an unmistakable golden crest and rump, green patches on its back, a bright red body, and its legs and bill are yellow.

Golden pheasants feed on the ground on grain, leaves and invertebrates, but roost high in the trees at night. This very colorful species is commonly seen in zoos, aviaries, on farms and in gardens worldwide, but in the wild, they hide in the dark forest during the daytime and retreat to their tree-top roosts for the night. If startled, they can burst into flight at great speed.

9. Snow petrel (Antarctica)

An odd-one-out among the species I have selected, and its inclusion reflects its pure white plumage, jet-black eyes and beak, and its bravery in breeding as far south as the Geographic South Pole. It lives on krill and has to travel to the open sea to find its food. The name petrel is of unclear origin but is believed to come from the bird’s habit of running on water before taking off. Today, an estimated 4 million birds inhabit the Antarctica Continent and surrounding islands.

10. Gouldian finch (Australia)

These birds are native to the tropical grasslands of northern Australia, are extremely attractive and strikingly colorful, and can morph into different colors on their face while retaining a consistent pattern elsewhere, combining greens, blues, orange and purple. For example, there is the black-headed, red-headed and yellow-headed Gouldians, and a few even have an orange face. The explanation is that they regulate the production of melanin and that different amounts cause the color differences (polymorphism is the technical term). The species was, until the late 1960s, trapped and exported as cage birds, and some estimates suggest that less than 2,500 exist today in the wild.

OTHER BIRDS: I confess there are many other species of beautiful bird that deserve a mention; just a few include the peacock (India), hyacinth macaw (S. America), flamingo (Americas, Africa and parts of Europe and Asia), condors (Americas), scarlet ‘I’ iwi (Hawaii), mandarin duck (Asia), Atlantic puffin (N. America and Europe), yellow-billed cardinal (Central South America), great hornbill (Asia), Victoria-crowned pigeon (New Guinea – Asia), bohemian waxwing (N. America), Adelie penguin (Antarctica), king parrot (Australia), Vulturine guinea fowl (NE. Africa), several species of kingfisher (Americas, Europe, and Asia)), and of course, the bald eagle (N. America).

Hopefully, my top ten and the ones listed above, plus the quetzal and hoopoe, can influence your personal selection.

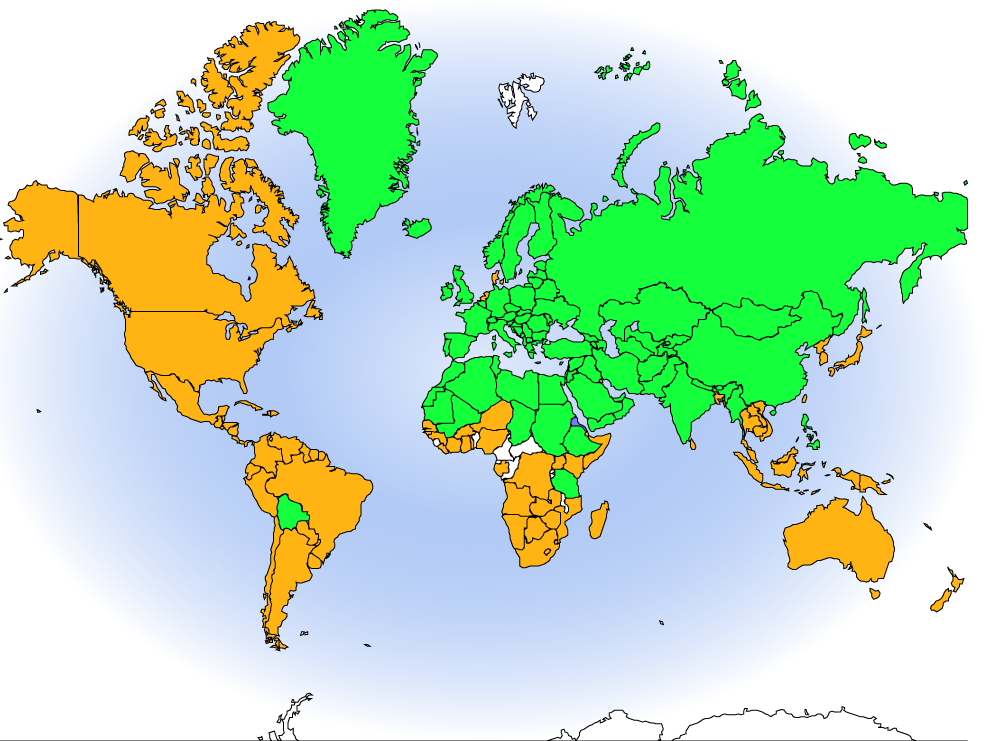

Rock Pigeon (wild and feral) Range Map: green – native and/or nesting: orange – introduced

Rock Pigeon (wild and feral) Range Map: green – native and/or nesting: orange – introduced

Band-tailed pigeon Range Map

Band-tailed pigeon Range Map

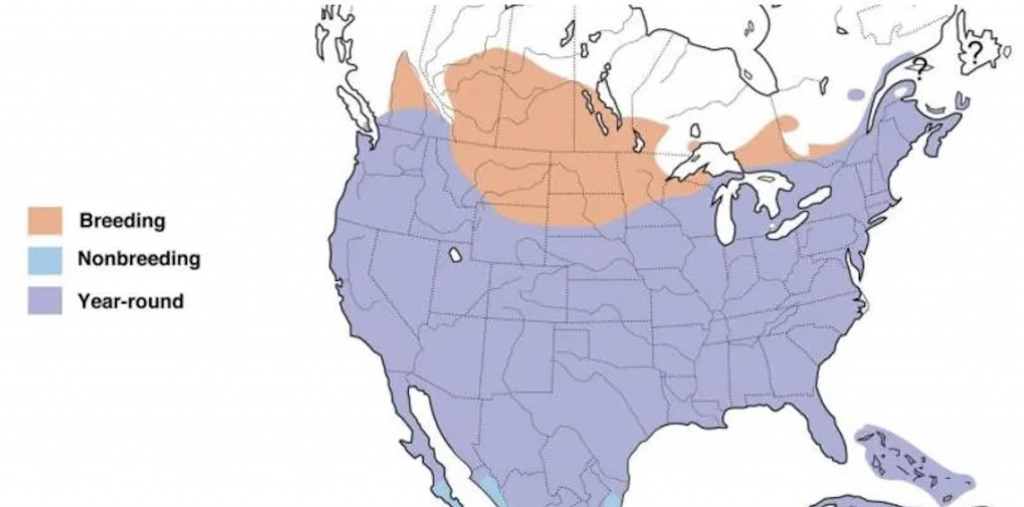

Mourning dove Range Map

Mourning dove Range Map

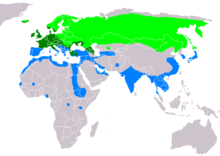

Eurasian common teal Range Map: light green – nesting, dark green – all year round; blue – wintering

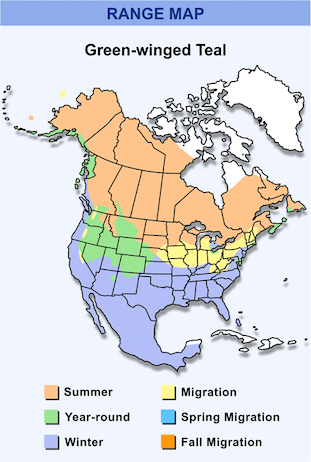

Eurasian common teal Range Map: light green – nesting, dark green – all year round; blue – wintering Green-winged teal Range Map

Green-winged teal Range Map

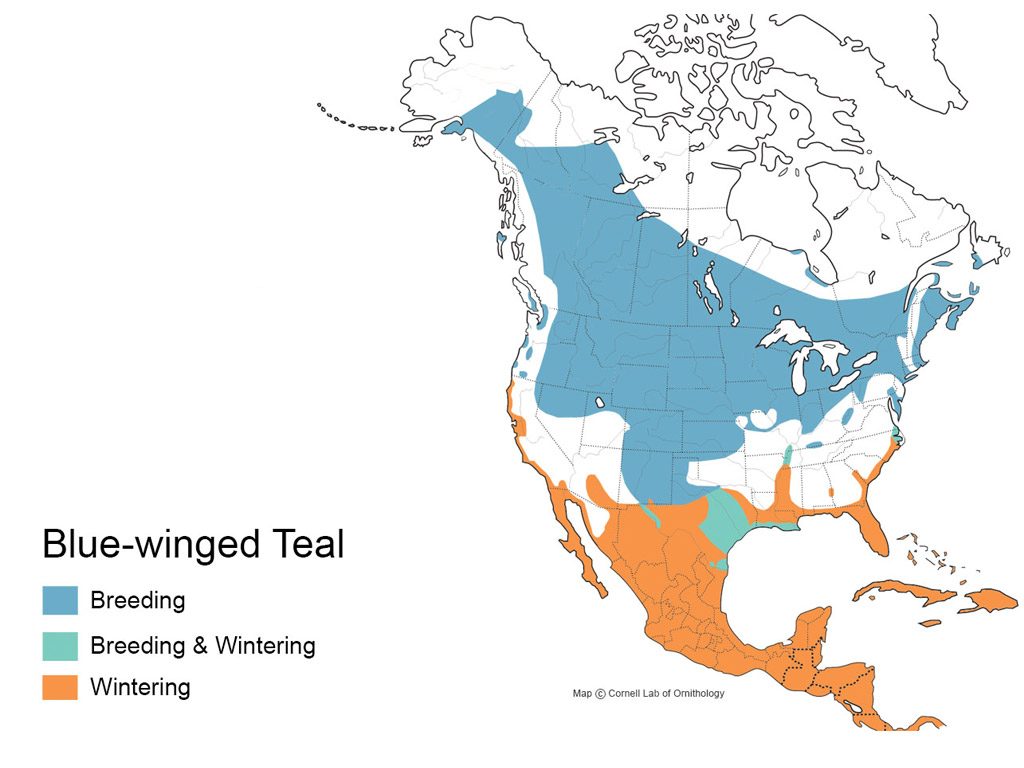

Blue-winged teal Range Map

Blue-winged teal Range Map

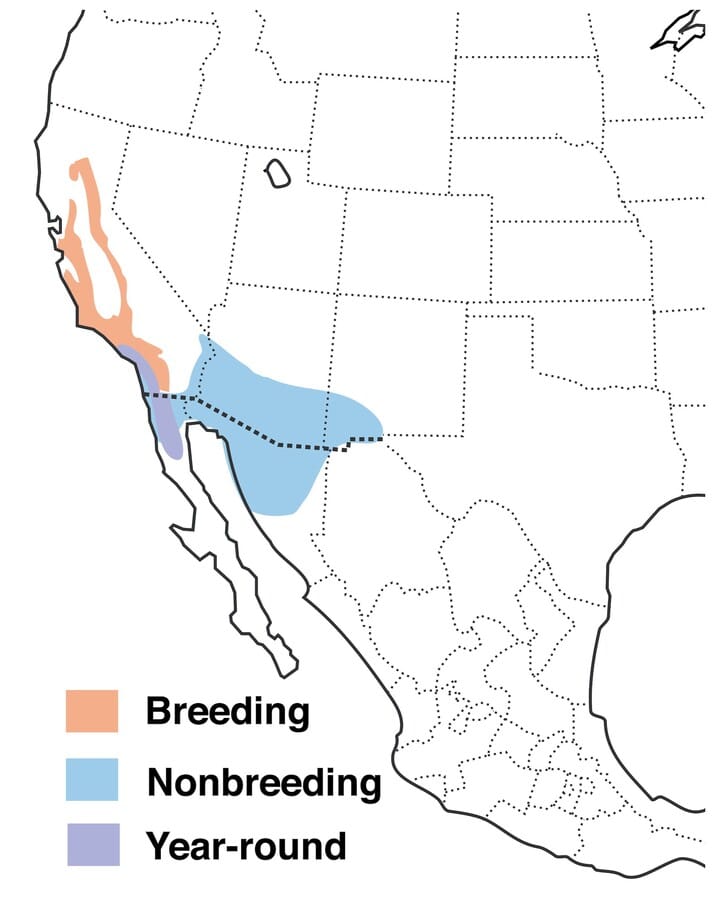

Cinnamon teal Range Map

Cinnamon teal Range Map Canvasback (male and female)\

Canvasback (male and female)\

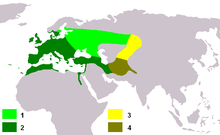

European goldfinch range map: light green – summer; dark green – all year; Himalayan subspecies: yellow – summer; moss green – all year

European goldfinch range map: light green – summer; dark green – all year; Himalayan subspecies: yellow – summer; moss green – all year Himalayan goldfinch

Himalayan goldfinch

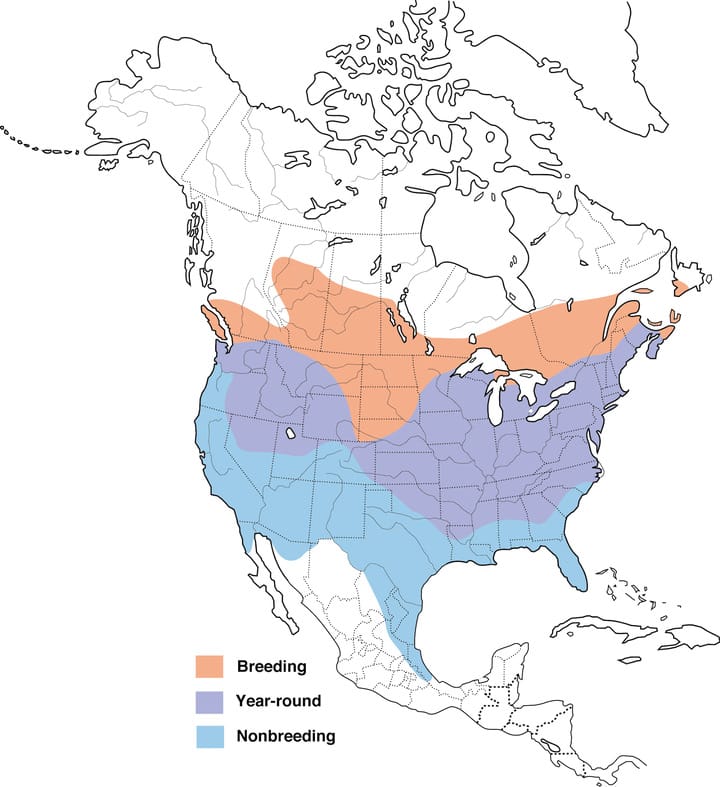

American goldfinch Range Map

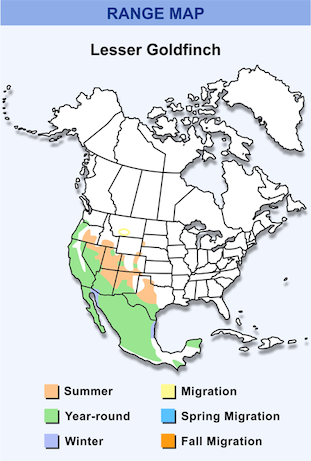

American goldfinch Range Map Lesser goldfinch Range Map

Lesser goldfinch Range Map Lawrence’s goldfinch Range Map

Lawrence’s goldfinch Range Map