Sabine’s Gull

Photo Credit – eBird

On a recent pelagic birding cruise out of Ventura, CA., I spotted my first Sabine’s Gull, a small, delicate seagull Sir Edward Sabine first described in 1818. Unlike most seagulls, these are readily identified but rarely seen because they migrate well offshore. Sabine’s Gulls are one of about 50 seagull species worldwide, and identification includes long-pointed wings, a slightly forked tail, a charcoal grey head (which disappears in winter), a geometric pattern on its wings and back, and a tern-like flight pattern. Its legs are black, and the dark bill has a yellow tip.

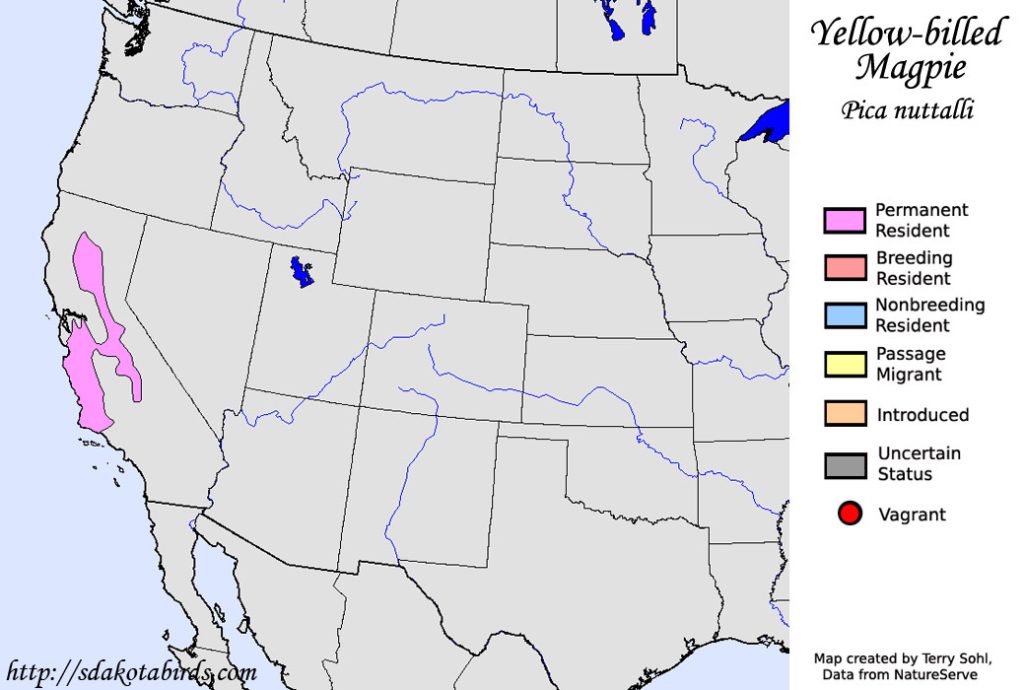

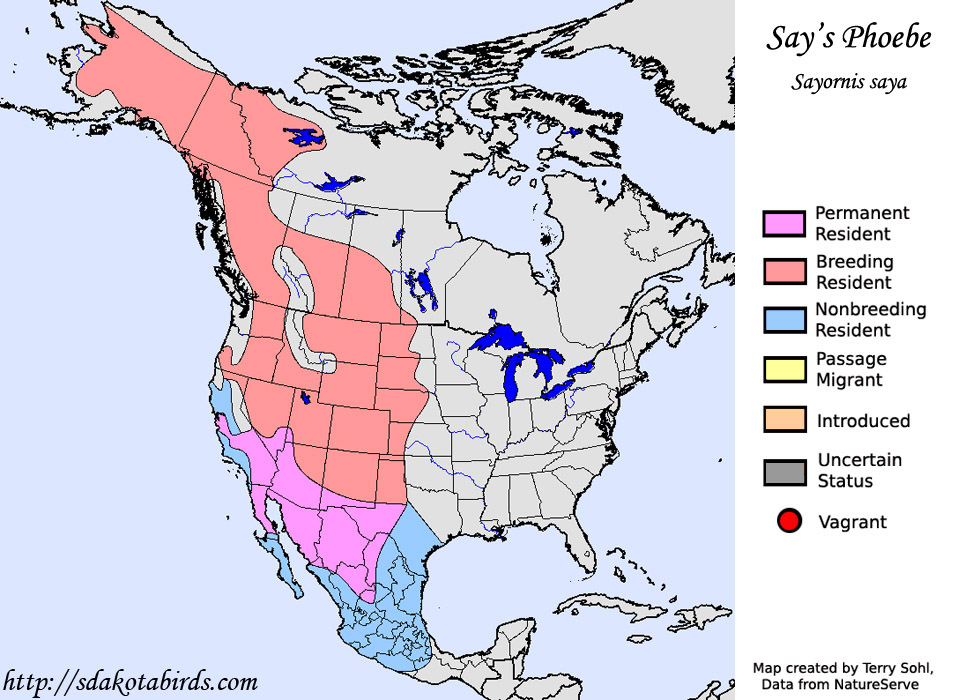

The Sabine’s Gull’s range is global. However, breeding habitat is restricted to the marshy arctic tundra from Siberia, Alaska, across Canada, to Greenland, and once nesting is over, they fly south along the coastlines, either to South America (mainly Peru) or to the west coast of South Africa, a return journey of about 22,000 miles (35,000 km). They winter offshore in waters a few miles off the coast. Typically, you see them during their migration from May and August through October. Their global population is around 340,000, and vagrants appear in most parts of the world. However, I never saw one in my early bird-spotting days in the UK.

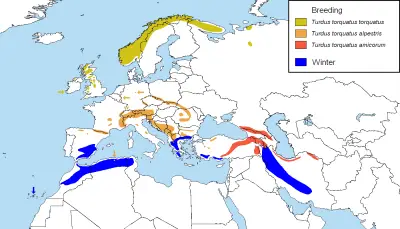

Sabine’s Gull Range Map

Photo Credit – Semantic Scholar

(blue=winter; purple = breeding)

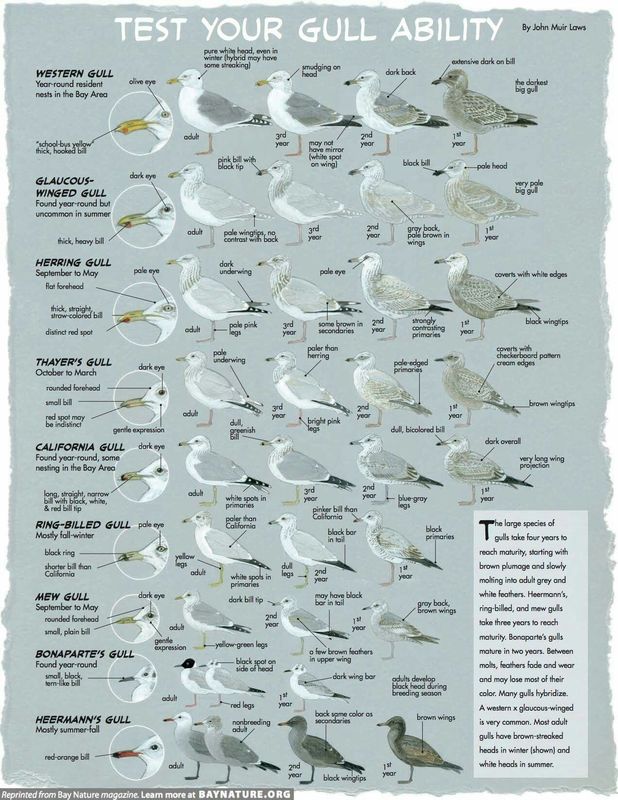

The new sighting resurrects the problem of identifying seagulls. You see these birds most of the time, but often, they look alike except for their size. Here are some ideas that may help you distinguish between various species. My examples focus on varieties in California and the United Kingdom, although I acknowledge many other species elsewhere. My past bird blogs have included the Great Black-backed Gull and Western Gull in April 2020, and in February 2020, I published a story about the Northern Fulmar. Fulmars look like seagulls but are related to petrels.

Below are species you will likely see in California and the United Kingdom; some are present year-round, and others visit during winter. I have excluded rare migrants:

CALIFORNIA: California Gull, Western Gull, Glaucous-winged Gull, Heermann’s Gull, Ring-billed Gull, Bonaparte’s Gull, Herring Gull, Yellow-footed Gull, Short-billed (formerly Mew) Gull, Sabine’s Gull, Iceland (formerly Thayer’s) Gull, and Black-legged Kittiwake.

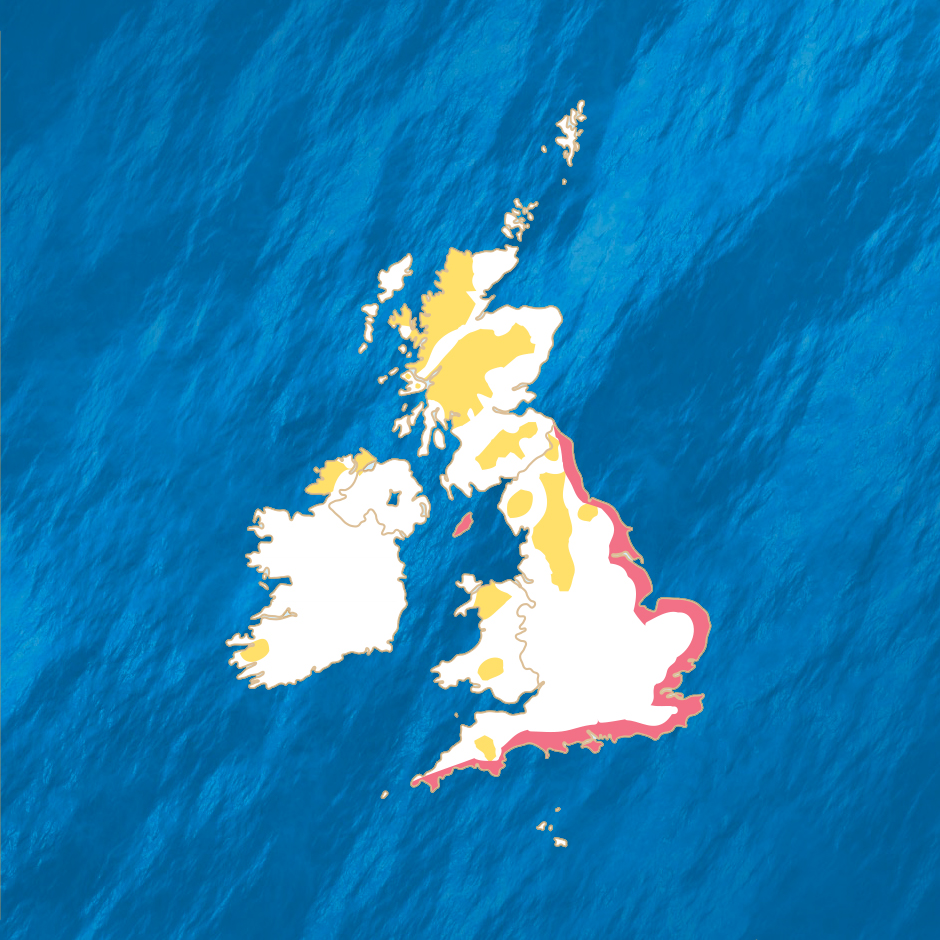

UNITED KINGDOM: Herring Gull, Kittiwake, Black-headed Gull, Lesser Black-backed Gull, Common Gull, Greater Black-backed Gull, Yellow-legged Gull (separated from Herring Gull 2005), and Mediterranean Gull.

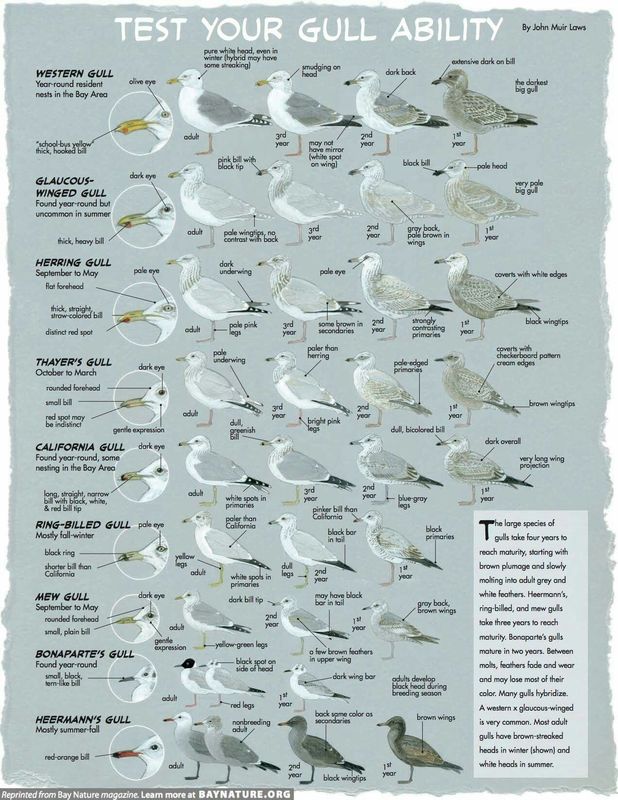

Identification of California Seagulls

Photo Credit – BAYNATURE.ORG

Note: Mew Gull was renamed Short-billed Gull in 2021.

Given the large numbers of seagulls and the fact that many species look alike, it is helpful to have a process to assist in identification. Avoid trying to identify juveniles and look for adult birds. Adult plumage takes two to five years to develop. Also, some gulls hybridize with other species, such as both the Herring Gull and the Western Gull, with Glaucous-winged Gulls. The former crossbreed is known as the “Cook Inlet Gull” (named after an inlet in Alaska where large breeding colonies exist), and the latter is the “Olympic Gull” (a reference to Puget Sound in northwestern Washington).

Set Your Expectations: Research the area you visit and consider the time of year to determine what you will likely see. Know which birds are common, such as Western Gulls and California Gulls in California, and Herring Gulls and Black-headed Gulls in the UK. However, seagull spotting is problematic from a distance, and many of the features I list are only discernible through strong binoculars or expensive telephoto lenses.

Size of the Seagull: This may be tricky if all the birds you see are the same species and, therefore, the same size; if not, how large is the one you are trying to identify? Large Gulls include the Western Gull, the Greater and Lesser Black-backed Gulls, the Herring Gull, the Yellow-footed Gull and the Glaucous-winged Gull. Representatives of small gulls include Bonaparte’s Gull, Black-legged Kittiwake, and Short-billed Gull.

Habitat: Although most gulls choose coastal environments, a few spend time at sea, such as the Sabine’s Gull and the Black-legged Kittiwake, and others venture inland, including in North America, the California Gull, Herring Gull and Ring-billed Gull; the latter is the one you will most likely see far from the ocean. Others, like the Bonaparte’s Gull, will visit inland waters such as lakes, wetlands, sewage ponds, creeks, and river mouths. Expect to see Herring Gulls in the UK and the Ring-billed Gull in North America at refuse dumps.

Plumage: This is critical; look at the color of the seagull’s back. Is it pale silver gray, slate gray, dark gray, or black? Are its wing tips black, such as the Herring Gull, Kittiwake (Europe), Lesser Black-backed Gull, or dark grey, like the Glaucous-winged Gull? The California Gull has the most extensive black wing tips. The Western Gull’s dark tips are the same color as the rest of its back. Also, is the gull black-headed or white-headed, especially during the breeding season?

Bill Color and Shape: Western Gulls have yellow bills with red spots, and adult California Gulls have yellow bills with a small black ring and red spot on the lower mandible. Adult gulls have a red spot on their bills to stimulate the regurgitation of food for the chicks. Herring Gulls are yellow-billed, a color that is common among gulls. Other colors include scarlet for Mediterranean Gulls (Europe), reddish-orange for Heermann’s Gulls, dark red for Black-headed Gulls (Europe), and small black bills for Bonaparte’s Gulls.

Leg Color (if the bird is standing): The Geater Black-backed Gull (Europe) has pale pink legs, while the Lesser (Europe) legs are bright yellow. Other colors include dark red for Black-headed Gulls (Europe) and Bonaparte’s Gull, scarlet for Mediterranean Gulls (Europe), and black for Heermann’s Gull and Black-legged Kittiwake.

Eye Color: For adults, the color may be dark brown/black (California Gull, Glaucous-winged Gull, Short-billed Gull (formerly Mew), Common Gull (Europe)), Heermann’s Gull, or pale yellow (Herring Gull); the Western Gull has orange around its olive eyes, and the Iceland (Thayer’s) Gull has a red ring. The Black-headed Gull (Europe) possesses dark eyes but with a white crescent behind its eyes.

Behavior: Many gulls are comfortable among humans; they might try to seize your food or attack you. Heermann’s Gulls enjoy taking fish from other birds, especially Brown Pelicans. The Bonaparte’s Gull is the only gull that nests in trees (others nest on the ground, rooftops or rocky outcrops). California Gulls chase and catch brine flies across the mud, and Western Gulls eat starfish. All are noisy and devour just about anything.

UK Seagulls

Photo Credit – Integrum Services

Black-headed Gull (summer)

Photo Credit – Cornell Lab of Ornithology

Mediterranean Gull (summer)

Photo Credit – eBird

Corn Crake Range

Corn Crake Range Corn Crake Nest

Corn Crake Nest Silage

Silage Female Common Pheasant

Female Common Pheasant Grey Partridge

Grey Partridge