Bald Eagle in Marin County

(Photo Credit – Elyse Omernick, Marin Living Magazine)

A friend of mine recently sighted a Bald Eagle near Fairfax, CA. an event that was inconceivable a few years ago. The Bald Eagle returned to Marin County, CA. in 2008 after 100 years absence, and its numbers have increased ever since. The trend is consistent with nationwide numbers that show there were only an estimated 450 breeding pairs of Bald Eagles in the continental United States during the 1960s, whereas today the number has increased to over 10,000.

So what is going on? Global warming theoretically should push birds further north, beyond the lower 48 states. Clearly, this is not happening. The end of persecution and the banning of certain pesticides appear to explain the contrary trend.

Bald Eagle in flight

Bald Eagle in flight

(Photo Credit – AP)

In the past, Bald Eagles were hunted for sport, slain because they were believed to be a menace to livestock and fisheries, and destroyed for money by bounty hunters. During the period 1917-52, bounty hunters in Alaska killed more than 100,000 Bald Eagles. The United States Bald Eagle Protection Act, enacted in 1940, made the killing of Bald Eagles illegal, but Alaska was exempt until it accepted statehood in 1959.

The population decline continued after this legal intervention because of the arrival of the pesticide DDT that made the shells of the eagles’ eggs thin and easily broken. It was banned by the United States in 1972, but still the population declined. In 1978 the species was declared endangered by the US government, and as a result of interventions, by the mid1990s, the population in the lower 48 states had increased to 4,500 pairs, and to 6,300 pairs by 2000. Today, lead poising still poses a threat to Bald Eagles. Hunters and anglers leave tons of lead behind each year, and an amount the size of a grain of rice can kill a Bald Eagle within 72 hours. Habitat loss also remains an issue, as do lethal collisions with powerlines and wind turbines.

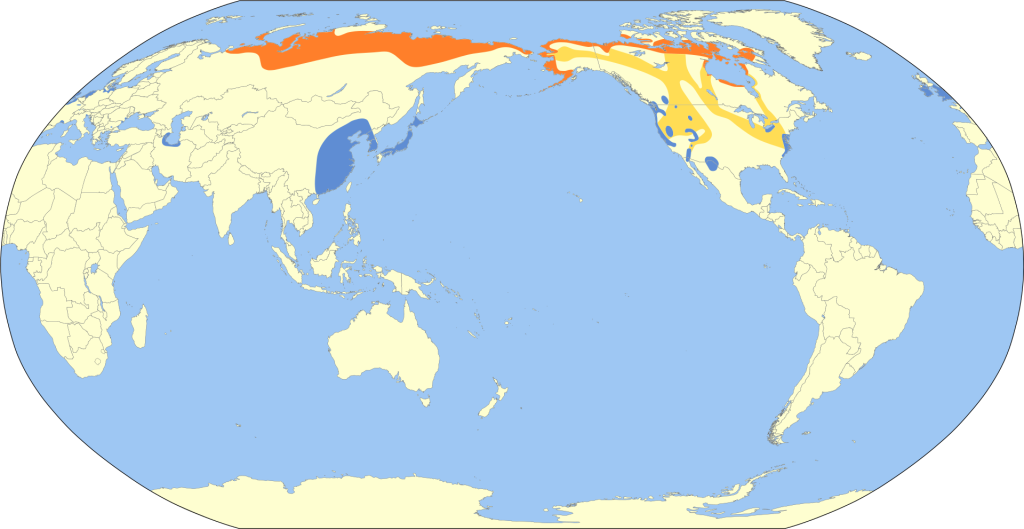

Bald Eagle Range Map

Bald Eagle Range Map

(Photo Credit – Cornell Lab of Ornithology)

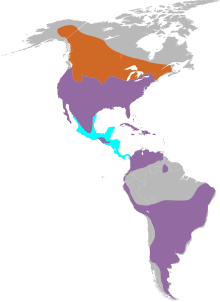

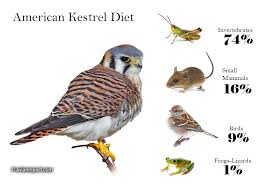

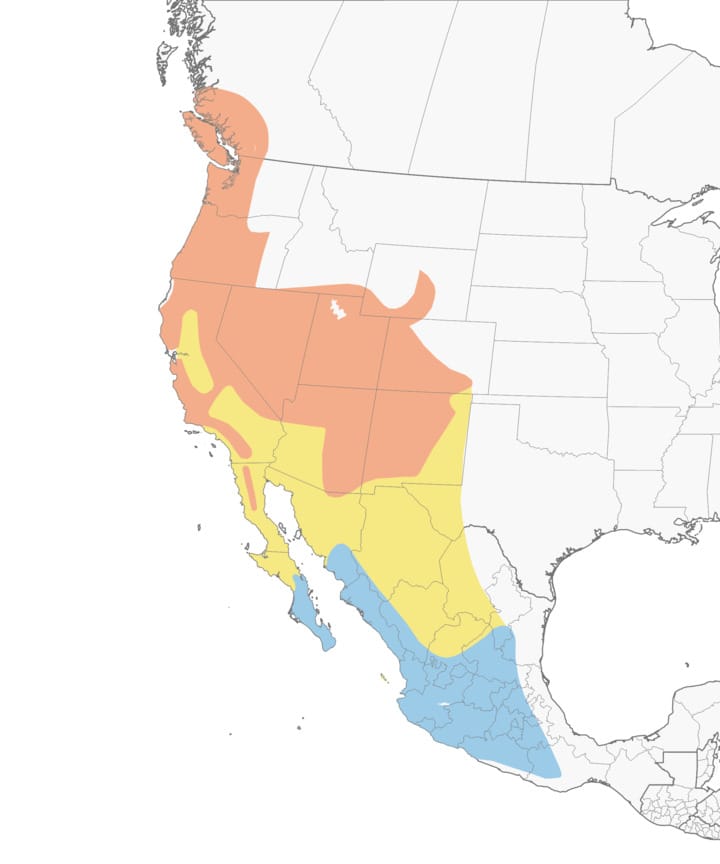

Bald Eagles mostly eat fish, up to 90 percent of their diet. They will also take the occasional waterfowl, seabirds, live animals, such as rabbits and squirrels, and eat carrion. Consequently, their preference is to live close to bodies of water containing fish, and also to have access to stands of tall, old-growth trees for perching, roosting, and nesting. Primary locations are coastal regions and inland where there are large lakes, rivers, or reservoirs. The species is native to North America, and ranges from Alaska through Canada, and as far south as northern Mexico. Southern and west coast birds often remain in their breeding territory all year, whereas northern birds migrate for winter. The best time to see Bald Eagles in California is during winter, mainly from December to March, when hundreds of migrating birds arrive from the north.

I have been fortunate enough to observe Bald Eagles in Alaska and Wyoming, but never during my childhood days in England, as evidenced in my novel She Wore a Yellow Dress. The species fails to appear in Europe except for very rare reports of vagrants in Ireland.

Bald Eagle chasing an Osprey

Bald Eagle chasing an Osprey

(Photo Credit – Phil Lanoue Photograhy)

The arrival of the Bald Eagle brings with it its own risks and consequences. Rather than carrying out their own fishing, Bald Eagles will choose to chase after birds that have already caught fish, and especially Ospreys. They harass the Osprey until it drops its prey in mid-air, and the eagle swoops down to collect it. Bald Eagles have excellent eyesight and can hunt from as high as 10,000 feet (3km). They see three times as far as humans, and have a 340 degree field of vision. Marin County has already experienced declines in its Osprey population. In the area of Kent Lake (reservoir created in 1958), there once were 50 or so Osprey nests; that number is now down to about 10.

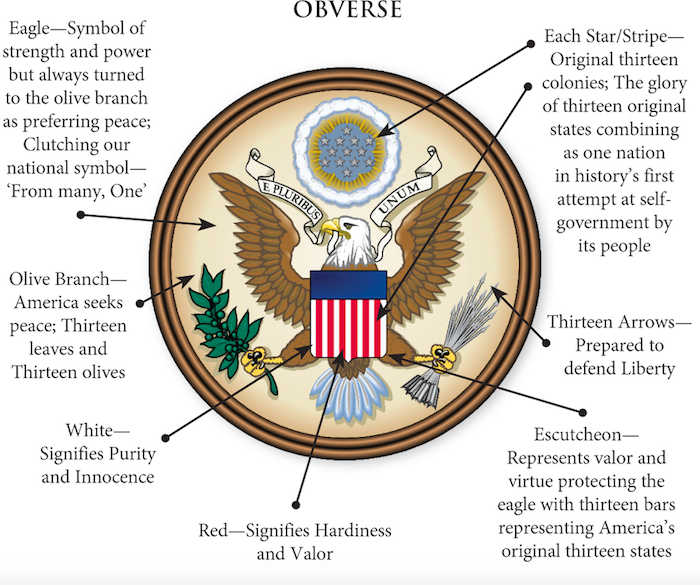

Great Seal of America

Great Seal of America

(Photo Credit – American Heritage Education Foundation)

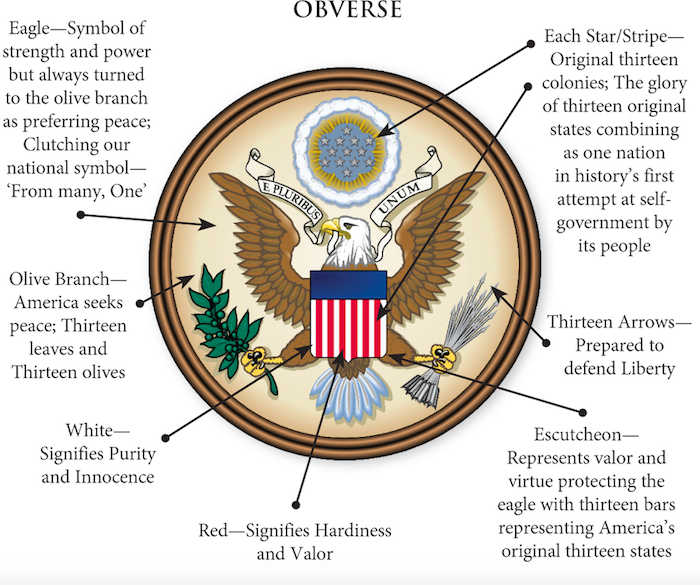

In spite of these behaviors, the Bald Eagle was chosen as the national bird of the United States around 1789, attracting disparagement from the then President Benjamin Franklin who wrote that “the Bald Eagle is a bird of bad moral Character. He does not get his Living honestly…. (he) is too lazy to fish for himself. Besides, he is a rank Coward”.

In 1782, when the design of the Great Seal was approved, the Bald Eagle was adopted because of its fierce beauty, proud independence, and powerful strength.

Adult Bald Eagles are readily recognizable. They are the largest birds of prey in the United States. Their white head and tail with an evenly brown body are distinctive, they soar high in the sky on their long, broad, slightly-rounded wings, their tail is wedge-shaped, and their bill is a bright yellow. The name “Bald” has nothing to do with the absence of feathers on their head. The name derives from the Old English word “piebald”, meaning “white patch”, and is reference to their bright white heads. Males and females look the same, although the female may be up to 25 percent larger than the male.

Bald Eagle Juvenile

Bald Eagle Juvenile

(Photo Credit – Cornell Lab of Ornithology)

Recognizing juvenile Bald Eagles is not so easy. They do not exhibit the characteristic white head and tail until they are about five years old, and instead display dark heads and tails, with brown wings and bodies mottled white. For the first four years of their life they live a nomadic exploration existence.

Bald Eagle Nest

Bald Eagle Nest

(Photo Credit – American Eagle Foundation)

Once Bald Eagles mate, it is for a lifetime relationship, and the typical life span is around 25 years. Their nest is a large platform of sticks, typically built high in a tree, and used repeatedly over many years. The clutch size is one to three eggs, and they are laid relatively early during February.

The question for the future is whether communities will continue to welcome the return of the Bald Eagle, without reservations, or will decide to impose limitations because of the species’ behavior, or to safeguard human interests. For example, 30 year kill permits are now being issued to wind turbine energy developers to allow them to take or incidentally kill Bald Eagles, even though camera systems can be used to spot eagles and trigger shutdown of nearby turbines.

The species is no longer classified as endangered but the requirements of the Bald Eagle and Golden Eagle Protection Act still apply. The 1940 original Act was amended in 1962 to include the Golden Eagle. Criminal penalties may be imposed on any person who “takes, possesses, sells, barters, or offers to sell a Bald Eagle, alive or dead”, and penalties for violations were increased in 1972.

Global warming also threatens the birds’ future by impacting bodies of water and river systems that the Bald Eagle uses as its source of food.

Photo Credit – avianreport.com

Photo Credit – avianreport.com

Turtle Dove

Turtle Dove Eurasian Collared Dove Range Map

Eurasian Collared Dove Range Map Mourning Dove

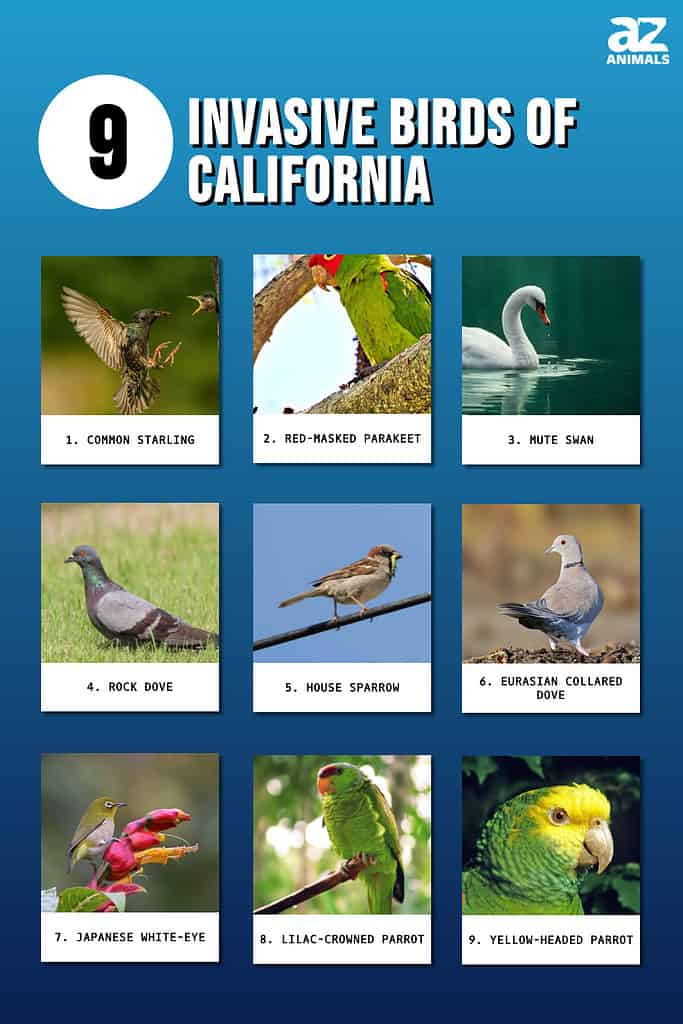

Mourning Dove Nine Invasive Birds of California

Nine Invasive Birds of California

Bald Eagle in flight

Bald Eagle in flight  Bald Eagle Range Map

Bald Eagle Range Map  Bald Eagle chasing an Osprey

Bald Eagle chasing an Osprey  Great Seal of America

Great Seal of America  Bald Eagle Juvenile

Bald Eagle Juvenile  Bald Eagle Nest

Bald Eagle Nest

A “not-so-good” image from Yosemite

A “not-so-good” image from Yosemite  Orange: breeding; yellow: migration; Blue: nonbreeding

Orange: breeding; yellow: migration; Blue: nonbreeding Steller’s Jay

Steller’s Jay  American Robin

American Robin  Dark-eyed Junco

Dark-eyed Junco  Yellow-rumped Warbler

Yellow-rumped Warbler Orange-crowned Warbler

Orange-crowned Warbler  Wilson’s Warbler

Wilson’s Warbler