Eurasian Siskin Male

There were not many birds I could see in the UK growing up that are also here in California. The siskin is an exception. It is a small finch, about the size of a sparrow, with a sharp pointed bill, pointed wing tips, and a notched tail. The two species, the Eurasian siskin and the North America pine siskin are similar in size and structure but differ in appearance.

Eurasian Siskin Female

The North American siskin is brown and streaky with subtle yellow edgings on its wings and tail. The Eurasian male is much more brightly colored, with bright gray-green plumage, dark cap, black wings with conspicuous yellow wing bars, a black tail with yellow sides, and an unstreaked yellow throat and breast. The female is more drab and may look like a pine siskin. It is possible that the Eurasian bird is the ancestor of the North American one, having reached North America, both via Greenland from the east, and along the Aleutian Islands into Alaska from the west.

North America Pine Siskin

The Eurasian siskin came on to my Life List after a visit to Spurn Point during 1962 when I saw several birds migrating. Around York, the species was only seen during winter when it appeared in small flocks along local river banks. Its UK breeding range was restricted to the upland wooded parts of Scotland, Wales, and the extreme north of England where its habitat was coniferous forest like its North American cousin. Siskins feed on seeds, especially from spruce and pine trees.

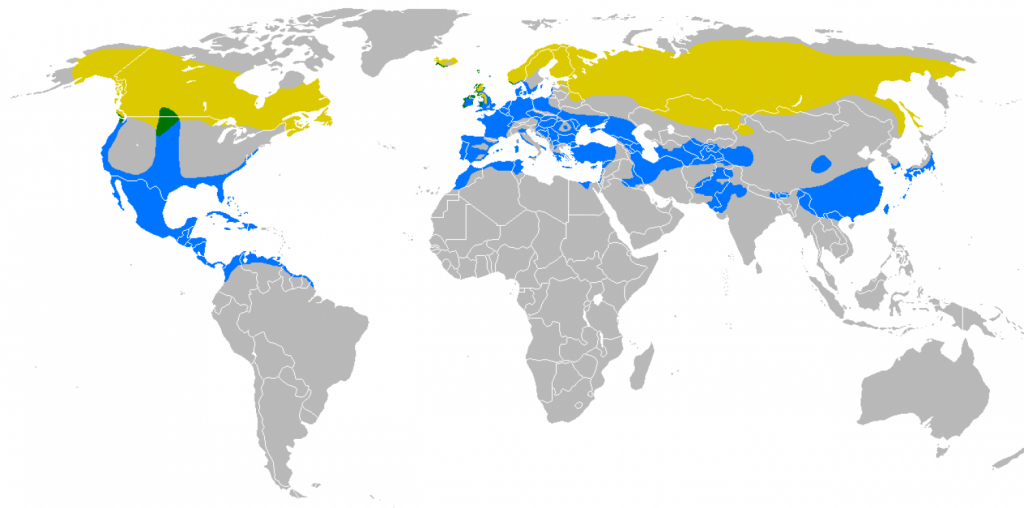

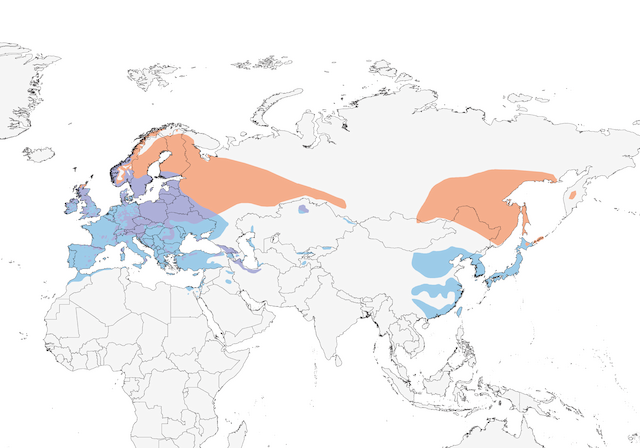

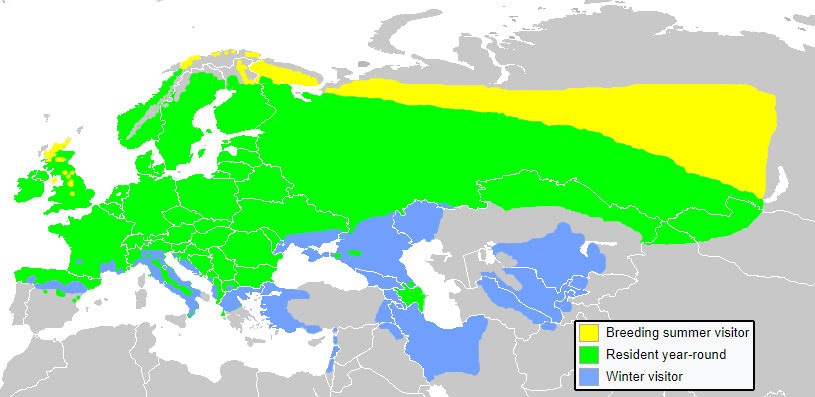

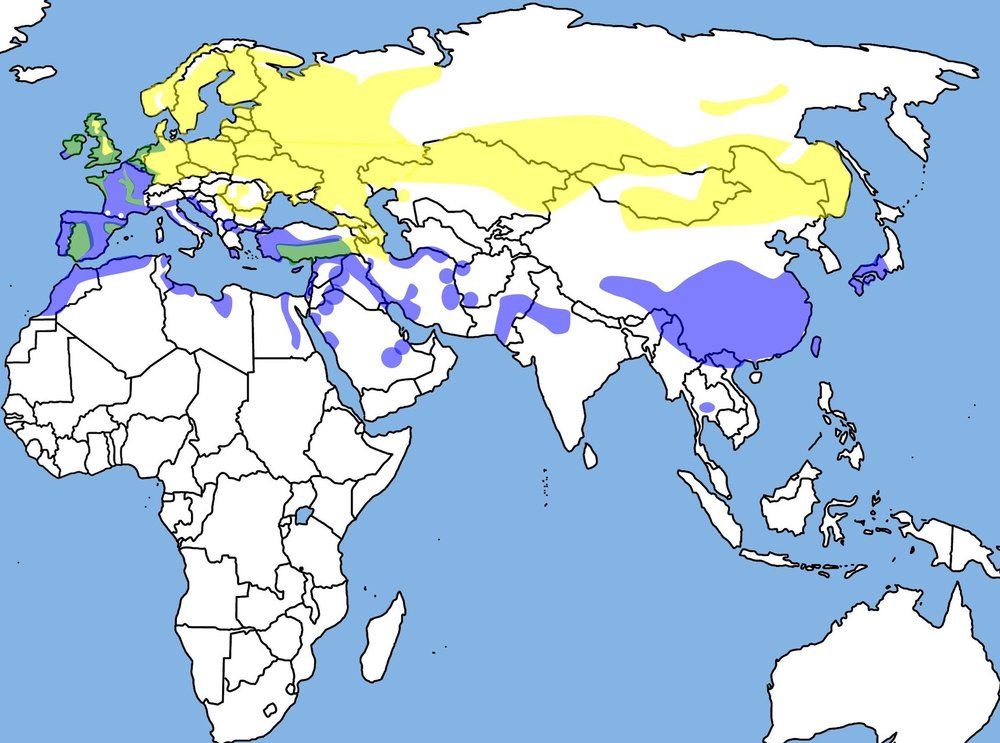

Globally, the Eurasian siskin ranges across large parts of Europe and Asia where they are often semi-permanent residents that only wander in search of food. Others, especially those breeding in northern Europe, may move south for the winter. A few vagrant Eurasian siskins have made it onto both coasts of North America.

Eurasian siskin Range Map: orange – breeding; purple – year-round; blue – non-breeding

Eurasian siskin Range Map: orange – breeding; purple – year-round; blue – non-breeding

Today the UK breeding situation has changed. There are now approximately an estimated 400,000 nesting pairs in Britain and they are spread broadly across the country. Indeed, by the late 1960s, the siskin was breeding as far south as the New Forest in southern England, as I mention in my novel She Wore a Yellow Dress, and from 1995 to 2015 their numbers rose 61 percent. In winter, they roam more broadly across the country in search of food and are joined by colleagues from Scandanavia. They even show up at garden bird feeders, especially during hard frosts.

It is noteworthy that while some bird species in the UK have registered dramatic declines in numbers over recent decades – such as the turtle dove, lapwing, cuckoo, and yellow hammer – others, like the siskin, have benefited from garden feeders and the increase in coniferous commercial plantations.

The siskin is named after the Swedish word sidsken and the Danish word siska, and in the past, in some parts of the UK, the birds were nicknamed aberdevines, at a time when they were kept in captivity. The origin of the word aberdevines is obscure. In North America, the related species of pine siskin has the nickname of pine chirper due to its habit of singing from the tops of conifer trees during the breeding season.

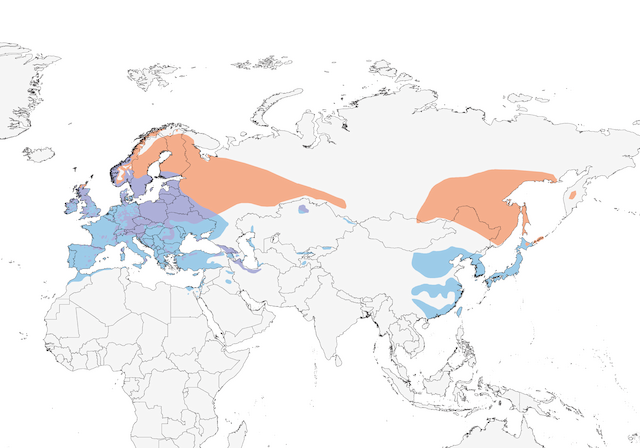

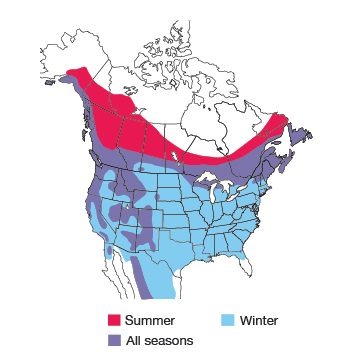

Like its Eurasian cousin, the North American pine siskin enjoys a wide range, with its breeding area spread across almost the entirety of Canada, Alaska, and the northern parts and western mountains of the United States. Its winter movements are erratic and sporadic, probably influenced by the availability of food, with large numbers moving south every other year. Its estimated population is 22 million birds. I enjoy their arrival at my bird feeders during winter where they compete for food with house finches, goldfinches, chickadees, and various other species.

North American pine siskin Range Map

North American pine siskin Range Map

Because field markings are not as striking, siskins may be confused with other types of finch and sparrows, especially the house finch, similar and related to the linnet in the UK, and named by the French for the habit of eating flax seed (from which linen is made). The female and juvenile house finches do not have red markings on the breast and forehead as displayed by the adult male, and can cause confusion when identifying a pine siskin.

North America House Finch

Eurasian Linnet Male

Both species of siskin travel in small and large flocks, sometimes in the 100’s or even 1000’s, especially outside the breeding season, and occasionally with other finches and similar-sized birds. They display a rapid, undulating flight pattern; also, siskins can hover and transit sideways while feeding, and you will see them spread their tails and wings to frighten off other birds while at the bird feeder. The species also forages in trees and on the ground for seeds, and during summer will catch insects for their young.

Eurasian Linnet Female

In many ways, the Eurasian and North American species behave similarly:

- Usually nest in conifer trees and high up.

- Move in large flocks outside the breeding season, twittering and making lots of noise in flight, sometimes traveling with other finches.

- Display the phenomenon of “irrupting”, by only moving southwards in large numbers some years, when there is a shortage of food in their home range.

- Have adjusted to changing habitats and appear not to be threatened by global warming.

- They are more likely to appear at garden feeders on wet days, when the seed cones on trees are closed.

Both species of siskin appear to have been highly successful in adapting to human intervention and have benefited from increases in commercial forestry and the availability of garden food supplies. Both are of Least Concern from a Conservation perspective.

Eurasian siskin Range Map: orange – breeding; purple – year-round; blue – non-breeding

Eurasian siskin Range Map: orange – breeding; purple – year-round; blue – non-breeding North American pine siskin Range Map

North American pine siskin Range Map

Yellowhammer nest

Yellowhammer nest Yellowhammer range map

Yellowhammer range map

Lapwing nest and eggs

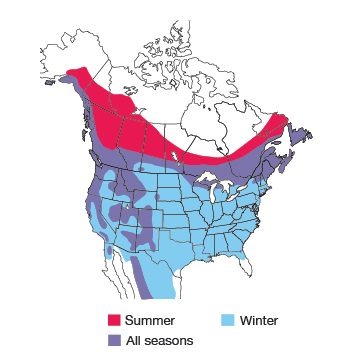

Lapwing nest and eggs Lapwing range map: yellow – breeding; green – year round; purple – winter

Lapwing range map: yellow – breeding; green – year round; purple – winter Lapwings in winter

Lapwings in winter Southern lapwing

Southern lapwing Californian killdeer

Californian killdeer Cute lapwings

Cute lapwings

Bempton Cliffs

Bempton Cliffs Gannets at Bempton

Gannets at Bempton Fulmar tubenose

Fulmar tubenose Fulmar range map: yellow – breeding; blue – wintering

Fulmar range map: yellow – breeding; blue – wintering Pacific dark morph fulmar

Pacific dark morph fulmar

European kestrel

European kestrel Sparrow hawk

Sparrow hawk Merlin eggs

Merlin eggs