Dotterel, a small plover, and a word in Britain used to describe a person easily deceived; why?

As a small wader and member of the plover family of birds, the dotterel is known for its friendly, sweet and trusting behavior towards humans. Consequently, it was hunted for sport, was easily caught, eaten by royalty as a delicacy during English Tudor times, and its brightly-colored feathers were used for fishing lures. Today, in Britain, it receives the highest conservation priority on the UK Red List of most endangered species.

I have never seen one of these medium-sized birds, or at least I have never been able to identify one. Many years ago, I and a friend watched a bird that flew like a plover and displayed the characteristic run-stop-and tilt-forward feeding behavior of species belonging to this bird family, but it did not display the usual plumage we associated with plovers. It was almost certainly a dotterel since I had already seen the more typical types of plover in Britain. I simply scribbled a note describing our sighting but took no further action. In my novel She Wore a Yellow Dress I describe some of my other bird watching disappointments. For example, I failed to see a peregrine falcon during a 1966 outing in Essex (chapter 12).

You can imagine dotterels running among the heath and grass of upland Scotland where today some 500 males incubate and rear their young? They nest on high, dry tundra. The female often ends the relationship with the male once the eggs are laid, leaving the male to take care of the offspring, and sometimes flies off as far away as Norway or Finland to find a new mate.

Dotterel nesting

Dotterel nesting

Dotterels display a colorful plumage, especially during the breeding season, when their reddish/chestnut-colored underparts are at their brightest. Their back is streaked grey and a warm brown, they have a black belly, and possess a broad white eye stripe and white band around their neck. The bill is short and the legs are yellow. They also appear along the British coasts during the spring and autumn migrations as they move between northern Europe and North Africa and the Middle East.

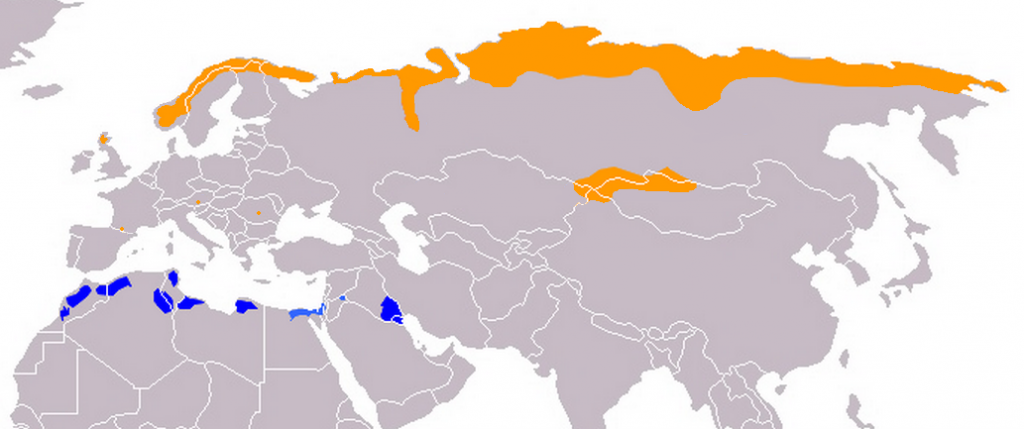

Dotterel Range Map: orange – breeding; blue – wintering

Dotterel Range Map: orange – breeding; blue – wintering

There are very few left breeding in Britain. A population decrease of nearly 60 percent has occurred during the past 30 years due to global warming. Breeding ranges have retreated up hill and the birds’ nesting pattern has altered because of vegetation change and a reduction in snow cover. With a longer season for vegetation growth, some nesting areas have been lost to long grass, and the early disappearance of snow that reduces the availability of insects lessens the areas where the dotterel can feed. Currently, the species nests in parts of Scotland and on occasion in the English Lake District. Not surprisingly, the Scottish Gaelic name for the dotterel translates into “the fool of the moors”.

Killdeer

You only find dotterels in North America as a casual visitor, although a few do make the journey from Siberia to Alaska, and nest in the west of the state. The first recorded sighting in California of a dotterel was on the Farallon Islands, off San Francisco, in September 1974, and every few years additional sightings are reported, including at Point Reyes only a few miles from where I live. So maybe one day I can add this species to my Life List of birds, but in the meantime I accept the abundant and perky, noisy killdeer, as the substitute.

My final comment has to do with climate change. It is not just the dotterel that is affected, but birds generally, and in particular those that migrate. British birds arrive on average 9 days earlier than in the past and are slowly pushing their range northwards. American robins arrive in the Rockies two weeks earlier and before worms and other food are available for their offspring. Some non-migratory birds such as the British great tit nests too late to make use of the abundant caterpillars that emerge earlier because of warmer winters. Plants leaf sooner, that in turn causes leaf-eating larvae to hatch sooner. Rising temperatures, flooding, drought, wildfires, and sea level changes are all affecting the traditional habitat of birds and interfering with their food supplies.