Learning About Sparrows, Those “Little Brown Birds”

During the 1950s and 1960s, as a young birder in the north of England, I ignored the rather common, drab and inconspicuous-looking birds known as house sparrows and tree sparrows. Both are Old World species, distributed across Europe and Asia, and rarely migrate significant distances. The house sparrow forages for grain and seeds and household scraps, whereas the tree sparrow’s diet includes fruits and invertebrates. There was a third kind of “little brown bird” that I could see furtively skulking among the hedgerow, that I called a hedge sparrow. However, later in life, I was told it was not a member of the sparrow family, and I should call it a dunnock.

Eurasian dunnock (not a hedge sparrow!)

Eurasian dunnock (not a hedge sparrow!)

The house sparrow appears in my novel She Wore a Yellow Dress, in particular in Chapter 23, titled The Cockney Sparrer. Back then, in 1968, I worked at Ford in Dagenham, and the cockney people who I now worked with were supposed to chirp like sparrows and move around in groups like sparrows; hence their nickname of sparrers.

Unfortunately, it seems that these birds suffered due to their closeness to humans. Today, while the house sparrow population has stabilized, during the 1977 to 2006 period, their numbers declined about 70 percent, and the tree sparrow population fell by 93 percent. Agricultural change, pollution, the wider use of pesticides, more cats, less availability of waste food, and maybe even diseases, caused these reductions.

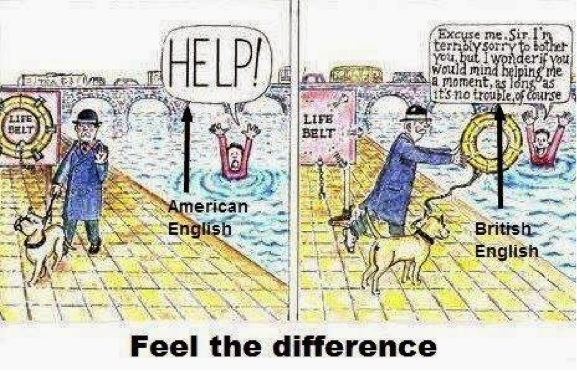

The Great Sparrow Campaign, China in 1958–1961

The Great Sparrow Campaign, China in 1958–1961

Another example of the decline in sparrows happened in China during 1958. The country implemented its Great Sparrow Campaign to cull the tree sparrow population because it was believed the bird was contributing to the declining yield of farmers’ crops. Several million birds were slaughtered. What was not realized was that the tree sparrow eats locusts, and because of the culling of sparrows, these insects multiplied, invaded the fields, ate all the vegetation they could find, and caused an even greater reduction in food supplies. The outcome was the Three Years of Natural Disasters during which tens of millions of Chinese died of starvation.

Once I moved to the United States, there was a dramatic change in the number and varieties of sparrows I could see, although there were still a few Eurasian house sparrows. Th Eurasian species was introduced deliberately into the United States, when eight pairs were released in Brooklyn, New York in the mid-1850s. These birds flourished and rapidly spread across the 48 lower states and parts of Canada. They arrived in California during 1910, and by the 1940s, it was estimated there were about 150 million house sparrows in North America They became regarded as pests because of the food they ate and the displacement of native species that they caused, such as robins, chickadees, and bluebirds. As in Europe, their numbers declined dramatically and the current population is estimated to be around seven million. Even so, the worldwide number of house sparrows is put at close to half-a-billion.

Where have all the sparrows gone?!

Where have all the sparrows gone?!

The highly active Eurasian tree sparrow also made its way to North America but was less effective in broadening its range. It was brought from Germany, with a dozen or so released in St. Louis during 1870. The species took hold but were restricted geographically because of the more aggressive and adaptable house sparrow.

Now I need to comment on North America’s species of native sparrow that I have come to know since moving to the San Francisco area. They comprise some 35 to 50 species, including several that do not carry the sparrow name, but for now, let me focus on the California varieties. Here we have the white-crowned sparrow (resident along the coast but with migrants inland during winter, and recognized by their distinctive zebra-like black and white head feathers ). Then there is the golden-crowned sparrow (a winter visitor with a golden stripe on its crown, bordered by black). Thirdly, there is the resident rufous-crowned sparrow (with a rufous crown, grey face, grey underparts and rust-colored stripes on its back); there is the song sparrow, the most widespread and most common resident in California, typically seen close to water (and usually singing its heart out from a perch); and then there is the chipping sparrow, a summer resident that migrates mostly to Mexico for winter (crisp and cleanly shaped, frosty-colored underparts, bright rusty crown and black line through the eye). Last but not least is the Eurasian house sparrow that I have already mentioned.

Somewhat rarer are the Lincoln sparrow (winter visitor that looks similar to the song sparrow except it has a buffy-colored appearance); the white-throated sparrow (winter visitor, with a white throat and yellow between the eye and bill); the grasshopper sparrow (summer visitor; brown and tan with slight streaking and a species whose population has tumbled 70 percent during the last 50 years, probably due to habitat loss, pesticides, and brood parasitism); the fox sparrow (winter visitor; rust-brown above and grey on the head); and the savannah sparrow (year round; brown above and white below, yellowish stripe over the eye, and crisp streaking). Occasionally, rarer species turn up such as the LeConte’s sparrow, and with so many species you can be excused from recognizing them all.

Just to add to the confusion, there are several species that are not named “sparrow” but belong to this family. Examples, frequently seen in my backyard, are the black-hooded dark-eyed junco, the all-brown California towhee, and the orange and black spotted towhee. All usually forage on or near the ground, and can be seen kicking up food with their feet.

So where does the word “sparrow” come from and why are North American birds given the name when they are not related to the family of Eurasian sparrows? They belong the “bunting” family, and it is presumed that early immigrants saw “little brown birds”, like the ones back home, and adopted the name “sparrow” because it was familiar to them. The English word “sparrow” is derived from the old Anglo-Saxon word “spearwa”, meaning “fluttering”.

Snow bunting

Snow bunting

Just keep things complicated, there are also several species of bunting in Europe. The one I often saw migrating was the snow buntings, and it is one that winters in the United States. Other North America species of bunting include the Lazuli, Lark, Indigo, Painted, and Varied buntings. In the UK, the corn bunting, reed bunting, cirl bunting, Lapland bunting, and yellowhammer (“ammer” means bunting in German) are the family’s representatives.

Inadvertently, we have another Americanism where the American word describes something very different from what it does in the UK. It joins such words as pavement, chips, biscuit, braces, and purse.