The Persecuted Family of Cormorants (Muckle Scarf)

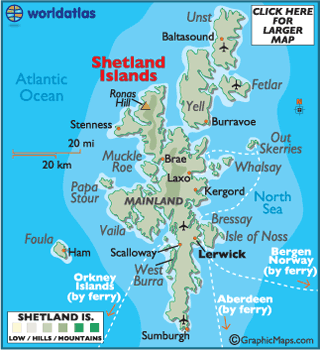

As my daughter leaves for a vacation on the Shetland Islands, I am featuring the long-time persecuted family of cormorants on my bird blog for this month. The Shetland Islands are a birders paradise, and both the sleek great cormorant (simply called the cormorant in the UK), and the European shag (a member of the cormorant family), breed here. The Shetlands are located about 130 miles (210 km) north, off Scotland’s north coast, and are an archipelago of about 100 islands, of which 15 are inhabited. This aquatic group of birds is superbly adapted to catch fish but for this reason, for centuries, has been slaughtered by vigilante-style hunters and, more recently, “culled” as part of government-sponsored wildlife programs.

There is no continent on which cormorants are not represented by at least one species, including Antarctica, where the distinctive white-breasted imperial shag lives. Worldwide, an estimated 35 to 40 cormorant species exist. Typically, they socialize and hunt in groups, nest in colonies, catch their prey underwater, and several species inhabit inland water sites as well as coastal areas.

Great cormorant – adult

Great cormorant – juvenile

Muckle scarf is the name given in the Shetlands to the great cormorant, and as best I can determine, the title is constructed out of muckle for large amount, and scarf for eating voraciously. The European shag is simply called the scarf on the Shetlands. Shag appears to be derived from the Old Norse words skegg, meaning “beard” and/or skag “to protrude”. The word refers to the bird’s tufted, forward-curving crest of feathers that appears at the front of its crown during the mating season.

Adult breeding European shag

Over the centuries, cormorants have built a reputation for greed and gluttony, and as a result, have suffered a long history of hostility and destruction by humans. As early as 700 BC, the Bible mentions cormorants as an “abomination” of birds not to be eaten, and Chaucer, in the 14th century, calls the bird a glutton. Shakespeare uses the cormorant in several of his plays to represent voraciousness, and in China and Japan, the bird is trained to catch fish for humans.

The word cormorant was first used during the 1300s based on the Middle English name “curmeraunt”, originating from the earlier Latin name of corvus marinus (“sea crow” or “sea raven”).

Both the great cormorant and the European shag were seen by me during my adolescent birdwatching years in the 1960s, but along the coast of Yorkshire, not on the Shetland Islands. The European shag is restricted to marine environments whereas the great cormorant can be found on all kinds of water, including inland lakes, reservoirs, and large river systems.

From a distance, the great cormorant appears primitive and malevolent, with black plumage, a long snake-like neck, large upright size, and a long hooked bill. In more detail, its feathers display a green-blue sheen bordered with black, and there is a patch of yellowish-orange skin on its face. Males and females are identical, and during courtship, they develop white patches on their flanks and hair-like white feathers on their head. Young cormorants are more brownish, and many have a whitish breast. Yet, like most cormorants, they look evil, hostile, and destructive.

Cormorants frequently are seen resting on perches, with their wings held out to dry. This is because a cormorant’s feathers turn wet while fishing and their wings have to dry to allow them to fly safely. This lack of waterproofing is in fact an advantage. While fishing, it allows them to trap water in their outer layer of feathers and achieve the same body density as the water in which they are diving. Their inner layer of feathers retains a thin coating of air around the skin to reduce heat loss. This balance between buoyancy and insulation enables the bird to swim like a penguin and dive like a seal, and to pursue fish in a broad range of temperatures and water depths.

Cormorants at Corte Madera Creek, CA – Wing-drying time

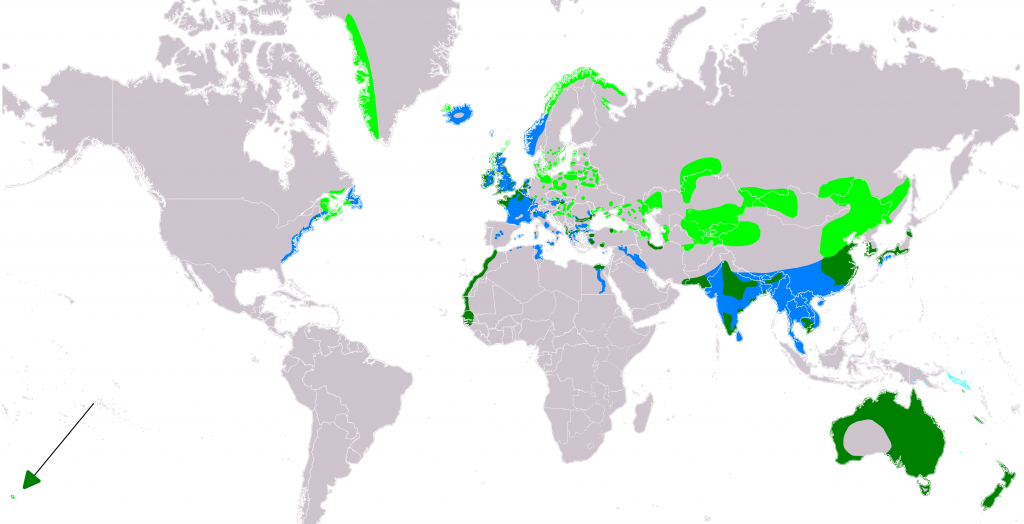

The great cormorant has achieved a wide global distribution, extending from the north Atlantic coast of North America, across the whole of Europe and Asia to Australia, and from Greenland south down to South Africa. The only continents on which the species is not present are South America and Antarctica. As you might imagine, they have established a large population estimated at around 2.1 million. Half that number is found in Europe.

Range map – great cormorant (dark green resident; light green breeding; light blue passage; dark blue non-breeding)

The European shag (or simply shag in Britain) is goose-sized and smaller and slimmer than a great cormorant. It has a bottle-green glossy plumage, a more delicate bill, a longer tail, and less yellow around its face. In some places it is called the green cormorant. It possesses the unusual habit of leaping out of the water before it dives. European shags prefer to be solitary, restrict themselves to coastal habitats, and nest on steep cliffs. It is nonetheless regarded as a pest because of its fish consumption, but is less harmful to the environment than the more common species of cormorant.

About half the world’s European shag population lives in the UK (110,000), and an estimated 6000 pair breed on the Shetland Islands. Adults usually stay close to their breeding grounds so the species is one of the most common birds seen along the Shetland Islands coastlines during winter. It is not present in North America.

Shag diving

Shag hunting

European shag range map (green breeding; blue non-breeding)

In North America, in addition to the great cormorant, there are five other native species. These are the double-breasted cormorant (the most common and found only in North America), Brandt’s cormorant, the pelagic cormorant, the red-faced cormorant, and the neo-tropic species that inhabits Central and South America but makes its way north during summer to central and northern Texas and other nearby states. All are similar in appearance, with mostly black plumage.

I have seen several neo-tropic cormorants in Costa Rica but none in the United States. Also, in Costa Rica, I have seen the anhinga, or snake-bird as it is sometimes called, that looks like a cormorant but is identified by a straight pointed beak that is used to spear prey, instead of using a long hooked bill like a cormorant. The North America distribution of red-faced cormorants is limited to Alaska where they are resident and nest on the Aleutian Islands.

Anhinga

Thus I have three species for me to spot here in California – the Brandt’s, pelagic, and double-crested cormorants – all of which I have seen. The Brandt’s cormorant, like the European shag, is strictly a marine bird, and ranges along the Pacific Coast from Alaska to the Gulf of California. In winter, those breeding north of Vancouver Island move south. At about three feet in height (91 cm), it is the largest cormorant on the West Coast and is characterized by its black plumage and the greenish iridescence on its back. The feathers at the base of its bill are pale buff, and during courtship it displays a vivid blue throat and eyes. About 100,000 birds are estimated to inhabit the Pacific Coast, with the largest colony (approximately 12,000 birds) on the Farallon Islands.

Brandt’s cormorant

Pelagic cormorants populate marine environments similar to the Brandt’s cormorant, but enjoy a slightly more northerly range, and their habitat includes bays and bodies of water connected to the sea. They are usually seen on their own or in pairs. The name of the species is misleading. While pelagic means “living on open oceans”, these birds rarely stray more than a few miles away from land. Their population is estimated at about 25,000, of which 60 percent live in California, and most winter close to their nesting site. Standing about two feet high (60 cm), they are the smallest cormorant in North America. Their plumage is violet-green and they have a coral-red patch on their throat, and white patches on the flanks.

The population of these and Brand’s cormorants appear to be more affected by the availability of the fish that they forage (anchovy and rock fish) than their relationship with humans.

Pelagic cormorant

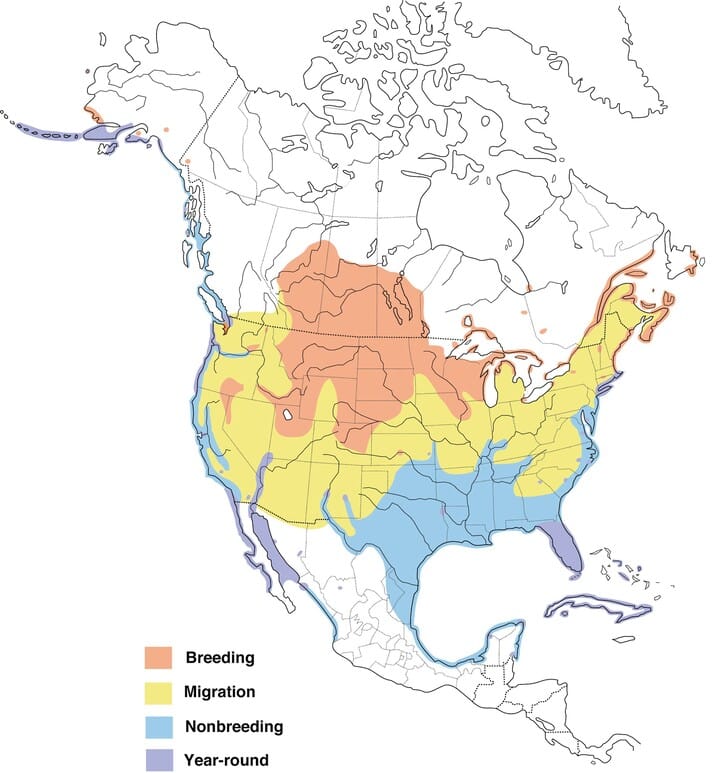

The larger double-crested cormorant, at two and a half feet in length (75 cm), is by far the most common in North America, and is the only species that is found across the continent. It ranges from the Aleutian Islands in Alaska down to Mexico, and from the north-eastern states down to Florida, the Gulf Coast, and Caribbean. Interior breeding birds migrate for winter to the south and south-eastern United States, and the western population moves to the Pacific Coast. Population estimates are hard to find, but their numbers (approximate calculations suggest up to two million) have increased during recent decades, renewing human dislike for cormorants and resurrecting actions to reduce their numbers.

This is the species I usually encounter along the Corte Madera Creek just north of San Francisco. The birds are usually flying low over the water, or are out fishing, or are perched on rocks drying their wings. My advice for identification is not to look for their double crest. These tufts of short feathers above the eyes appear only during the breeding season, and are the same color as the head feathers. Additionally, they are usually wet and slicked back against the bird’s regular plumage.

Double-crested cormorant

Range map

At a distance, double-crested cormorants are iridescent dark birds with snake-long necks. The color of their plumage is either deep brown or black with a bronze or greenish sheen, and their wing feathers are margined with a darker black. Closer too, you may see the distinctive orange-yellow naked skin on their face and throat, and also their aquamarine eyelids. The latter disappear during winter.

In summer, these birds breed in large colonies, often in trees, and build conspicuous nests made of sticks and other material, sometimes becoming unwelcome guests because of the acidic guano they produce. As well as foul-smelling, it can harm the soil, affect the vegetation, and also is a health risk for people and poultry.

Double-crested cormorants nesting

In the past, human interaction with cormorants has varied widely between regions and cultures. In some places, cormorants are welcome as a positive omen because they indicate the presence of fish whereas elsewhere they are despised because of their competition for the same food as humans. In Peru, deposits of cormorant guano are mined as fertilizer to grow food for humans. In China and Japan, cormorant fishing is used as a tourist attraction as well as for catching fish for human consumption. Unfortunately, in many other places, cormorants are subject to less tolerant relationships.

Cormorants lack natural enemies, and once the use of the pesticide DDT was banned during the 1970s, their numbers began to rapidly increase. Global warming has added to this trend by opening up new territories for breeding and feeding. Once again, cormorants are regarded as overabundant, and persecution has renewed because of the fish they take and the mess that they make during breeding. Estimates are that each cormorant eats one to one-and-a-half pounds of fish a day (500 grams), or around 10,000 pounds (4,500 kilos) in its lifetime.

While cormorants are legally protected in many countries in Europe and North America, exceptions have been introduced to allow for their culling in circumstances where they are allegedly causing a nuisance. Methods to reduce the population include trapping and shooting, introducing frightening devices, installing protective nets around fisheries, destroying nests and nesting habitat, oiling eggs (coated with oil) to kill the embryo, killing the young, habitat modification, and forced relocations. As a result, more than one hundred thousand cormorants are destroyed each year, not including the tens of thousands of eggs that are oiled.

Much has been written about this negative relationship and I have no intention of duplicating these stories. Should you be interested in understanding more about how humans and cormorants interact, I suggest you read the following books: The Double-Crested Cormorant – Plight of a Feathered Pariah by Linda Wires, and the Devil’s Cormorant by Richard King.

Cormorant hunting season

Hopefully, governments in future will use more humane, non-lethal solutions to control the growth in cormorant populations, such as restricting their habitat, improving fisheries management, relocating excess birds, and fertility management.

Meantime, I wish my daughter a pleasant vacation in the Shetland Islands and hope she will see some of the other Shetland breeding species that appear in California. Examples include the red-throated divers (loons over here), fulmars, puffins, red-necked phalaropes, arctic terns, whimbrels, and goldeneye ducks.

Thank you for reading this article.

Bird watching on the Shetlands