Migrant Birds, Featuring the Barn Swallow

Barn Swallow

Photo Credit – Birds and Blooms Magazine

My local Barn Swallows have arrived and have been constructing mud nests and feeding their offspring under the roof eaves of houses along the Corte Madera Creek near San Francisco. These avians make an annual pilgrimage, often in large groups, during early spring from as far away as Argentina, a journey spanning approximately 5,000 miles (8,000 km). They travel up to 600 miles (1,000 km) daily during daylight, indulging in a mid-air feast as they dart across the sky. Barn swallows eat only insects. Most other migrant birds travel under darkness, resting and feeding during the daytime so as not to be seen by predators. Barn swallows can quickly alter their course and altitude, accelerate when necessary and often soar too high to be pursued by raptors.

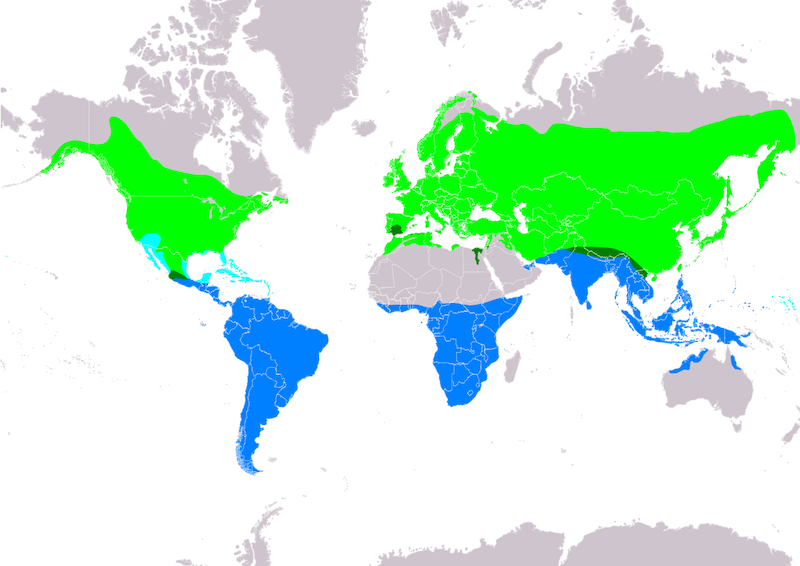

Barn Swallow Range Map

Photo Credit – Wikipedia

Green – breeding; dark green – resident; light blue – migration; blue – non-breeding

The Barn Swallow, a truly cosmopolitan bird, also breeds in northern Europe, northeastern Asia, the Middle East, and northern Africa. As a young bird enthusiast, I would eagerly anticipate their annual arrival at the Yorkshire farm, where they would promptly construct their mud nests in barns, sheds, and under the eaves of buildings. I would call them “the swallows “. They are the world’s most populous and widely dispersed swallow species. Other members of the Hirundinidae family seen during my childhood were the Sand Martins and House Martins. In California, there are these additional representatives:

- Cliff Swallow: Species nests in small colonies among coastal cliffs and highway bridges. It is the legendary swallow mentioned in the Mission San Juan Capistrano.

- Tree Swallow: nests in isolated pairs or small groups in natural and artificial cavities.

- Bank Swallow: This species is the Sand Martin in Eurasia. It excavates nests in burrows along the banks of rivers and streams and lives in large colonies.

- Violet-green Swallow: a fast-flying bird found near open water. Not very social and does not nest in colonies.

- Northern Rough-winged Swallow: common in coastal hills of southern California; nests in burrows excavated by other birds and animals, either singly or in small groups.

- Purple Martin: largest member of the swallow family; restricted to the mountains of California; nests in colonies.

There are approximately 90 Hirundinidae species worldwide. Swifts are unrelated and classified in a separate family, the Apodidae.

Photo Credit – A Way to Garden.com

WHY DO BIRDS MIGRATE?

- It’s in the genes of migrant birds. And it’s needed for new food sources and breeding locations; sometimes, they travel on ancestral routes rather than present-day ones. For example, the Northern Wheaters in eastern Canada, Alaska, and the Yukon do not fly south for winter. Those in the east cross the Atlantic to West Africa, and those in the west travel to Asia and East Africa. Not all birds relocate. Around 4,000 species migrate, about 40 percent of all birds.

- The Arctic Tern undertakes the longest migration, travelling 50,000 miles (80,000 km) each year between the Arctic and Antarctic. The longest “nonstop migrant” is the Bar-tailed Godwit (nearly 7,000 miles/11,000 km), and the fastest is the Great Snipe, traveling 400 miles (650 km) at speeds of up to 60 mph (95 kph). Some birds fly high (above 20,000 feet/6,000 m), including the Mallard, Whooper Swan, and Alpine Chough.

- Studies indicate that migration began millions of years ago and likely started in a north-south direction, maybe in response to glaciation cycles. Challenges during migration include bad weather (causing the arrival of vagrant species), predators, human hunting, human-made obstacles, and the need for food and rest on the journey.

Arctic Tern

Photo Credit – eBird

WHEN DO BIRDS MIGRATE?

- Species do not migrate simultaneously. Most migrant birds travel from late summer through the fall and return to their breeding grounds from late winter through the spring. Dates are not exact and influenced by weather conditions (storms and strong winds), food availability (especially insects), hormonal behavior that causes birds to build body mass before departing, and resource competition.

- Changes in the day’s light length (photoperiod) trigger birds’ travel restlessness and stimulate their genetic and physiological constitution. Temperature change may also influence this. Permanent residents do not migrate; short-distance migrants move from higher to lower elevations; medium-distance migrants relocate several hundred miles; and around 350 North American bird species are long-distance travelers.

- Most migrant birds take flight within an hour of sunset and fly through the night; some fast flyers, such as hummingbirds, finches, swallows, and swifts, travel in daylight, as do birds of prey, pelicans, and herons. Most species flock for migration to enjoy safety in numbers; a few, such as hummingbirds and some sparrows, will travel solo.

Seabird Migration

Photo Credit – World Migratory Bird Day

HOW DO BIRDS FIND THEIR MIGRATION DESTINATION?

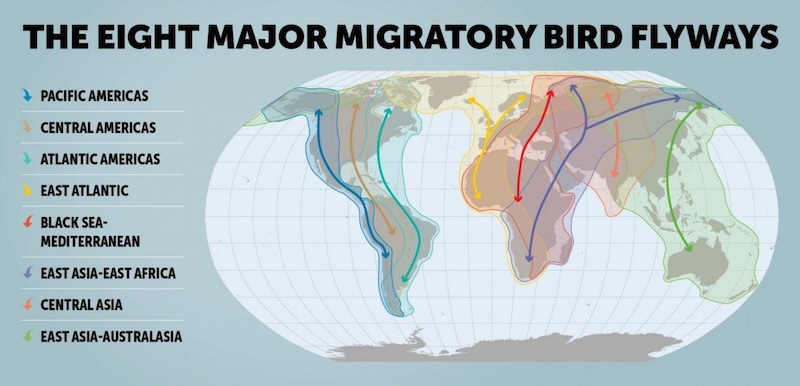

- Most migrant birds follow landmasses and use specific geographic flyways. Globally, there are eight major ones. North America has four: along the Atlantic and Pacific coasts, the Mississippi Valley, and the east side of the Rockies. Britain is dominated by the East Atlantic bird highway from Siberia, Canada, and Greenland, which extends to southern Africa; an estimated 90 million birds use this flyway. Three other highways are the Mediterranean and Black Sea routes, Central Asia, and Eastern Asia/Australia.

- Birds that migrate at night use stars and constellations; the sun is used during the day. Some species can see the earth’s magnetic field photochemically through their eyes, believed to be their navigational aid; others have magnetite-based receptors in their bills. These and in-built compasses allow birds to orient themselves according to magnetic intensity.

- Several species, such as terns, geese, swans, and cranes, escort their young during their first migration to prevent them from getting lost.

Photo Credit: Vermont Institute of Natural Sciences

WHAT IS THE EFFECT OF GLOBAL WARMING ON MIGRATION?

- Destination changes: Birds migrate further north as new territory becomes available and may nest at higher altitudes.

- Physical evolution: some long-distance migrants show signs of evolving smaller bodies, longer wings, and less weight to move further and faster.

- Departure times: some birds leave earlier for their breeding grounds as food supplies become available sooner. An English study of 20 species of migrant birds showed that arrival dates had advanced about eight days over 30 years for 17 of these species. Warming air and sea temperatures in the northern Pacific have a similar effect.

- Rise in Sea Levels: migrant waders will likely experience reduced habitat as mudflats and marshes disappear, and shore nesting sites will be lost.

In summary, there is more to learn about the effects of climate change on birds. There seem to be winners and losers, with some benefiting and increasing in numbers and others hindered and experiencing declining populations.

HOPEFULLY, THIS INFORMATION WAS USEFUL. THERE APPEARS TO BE MUCH MORE TO LEARN ABOUT BIRD MIGRATION AND HOW EACH SPECIES COPE WITH CLIMATE CHANGE.