American Kestrel, Small Falcon with a Large Appetite

Eurasian or Common Kestrel:

Photo Credit – Wikipedia

American Kestrel

Photo Credit – Cornell Lab of Ornithology

Thank you, Sonoma Land Trust, for connecting me with the beautiful American Kestrel, the smallest raptor in North America, during a recent visit to the Sonoma Creek Baylands. Its larger and less attractive cousin, the Eurasian Kestrel, featured throughout my early days of birdwatching in England. I saw them pass through Spurn Point in 1961, and they were common around York in the late 1950s. My earliest sighting was a pair that nested in an abandoned farmhouse near my home, but unlike Billy, in the novel A Kestrel for a Knave by Barry Hines, I never climbed the chimney to inspect the nest. The American Kestrel and Eurasian Kestrel remain common today, although their populations have declined for unclear reasons.

If you wonder about the origins of the word kestrel, no one seems to know with certainty. Maybe it is an Old French or Middle English word used since the 15th century and is most likely related to the bird’s cry.

Eurasian Kestrel Range Map

Photo Credit – CCNAB

Blue: year-round; Red: summer

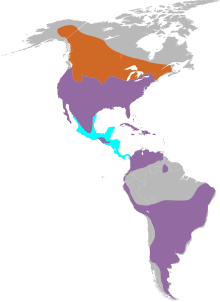

American Kestrel Range Map

Photo Credit – Wikipedia

Purple: year-round; Orange – summer breeding; Blue – winter, non-breeding

The American Kestrel was known as a Sparrow Hawk until the 1960s, and its name officially changed in 1983. It is not a hawk; it does not particularly like sparrows, and looks like and is related to the Eurasian Kestrel. Its life span in the wild is short, frequently less than two years. Its preferred habitat is open grassland, desert, scrub, and enough isolated tall perches to hunt. They are also known for their hovering, preparing to catch their prey. American Kestrels are both residents and long-distance migrants. Those breeding in the north are more likely to migrate, sometimes as far as Central America, but most spend winter in the southern United States. There are records of the Eurasian kestrel in northeast North America, Alaska, and British Columbia, so distinguish the two species carefully if you are in those places.

Their calls are distinctive and often heard as an excited series (three to six) cry of klee or killy.

American Kestrel male and female

Photo Credit – inaturalist

The American Kestrel is about the size of an American Robin and smaller than another North American bird of prey called a Merlin. Their estimated global population is four million, with 2.5 million in the US and Canada. Its Eurasian cousin is larger, closer to the size of a Crow, and bigger than a Merlin. It is less colorful, with male plumage consisting of a chestnut-brown back with darkish spots, a grey head, and a grey tail with a black band near its tip. A population estimate is around five million worldwide and one million in Europe. The current British population is about 65,000.

As seen above, the male possesses slate-blue plumage near the top of its wings, a rufous orange back with black barring, and its tail is the same color with a large black band towards its end. Since you often only see this bird from a distance, be sure in its identification it has pointed wings and a long tail. It will be fast in flight, pumping its tail up and down while perched, and can be noisy.

|

Photo Credit – avianreport.com

Photo Credit – avianreport.com

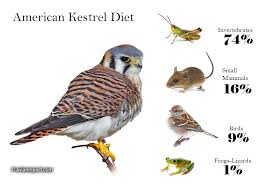

The species’ diet is diverse and changes depending on the time of year. Small mammals comprise a more significant part of the kestrel’s diet in winter, with fewer insects. However, when insects are bountiful, the bird can consume 10 to 20 percent of its body weight daily. Its success in capturing its prey is estimated to be very high for invertebrates, less for rodents, and under 50 per cent for birds. It hunts only in daylight but deters potential attackers using the back of its head. It has two black spots called ocelli (false eyes). They deter would-be attackers and possibly attract a mobbing response from songbirds, allowing the kestrel to catch some of them. It also sees ultraviolet light, permitting it to find food hidden in grass and undergrowth. This includes spotting the bright blue-green glow of mouse urine.

American Kestrels Nesting

Photo Credit – Cornell Lab of Ornithology

American Kestrels rely on natural or man-made cavities for successful nesting and will not breed if a suitable cavity is unavailable. This includes migrating kestrels returning to the same cavity each year. Bird boxes are welcome. However, it should be near the birds’ preferred habitat, away from outdoor pets, and a distance away from busy roads that cause a high rate of nest abandonment. Typically, the female will lay four to five eggs, and incubation becomes her full-time job, while the male brings her food.

Merlin

Photo Credit – Wikipedia

Sharp-shinned Hawk

Photo Credit – Cornell Lab of Ornithology

Above are two other species of raptor that you might confuse with kestrels.

Merlin: the distinctions are its slate grey back (not rusty); short, dark tail (not long and narrow); it rarely hovers; it flies fast with sudden changes in direction (versus the shallow, deliberate wing beats of the kestrel); and chases its prey (rather than hovers or perches before diving on the victim).

Sharp-shinned Hawk, or Sharpies as they are nicknamed: are roughly the size of an American Kestrel but have rounded wings and longer tails; there are heavy markings on their front, and they lack the kestrel’s red-brown on the back; their hunting style is very different; they hunt fast and furious, flying stealthily at low altitudes and aggressively then accelerating to catch their prey. It is also the raptor you might see waiting at the side of your backyard bird feeder. It has occurred in my backyard, but its presence seems more likely to be as an observer than as an assailant.

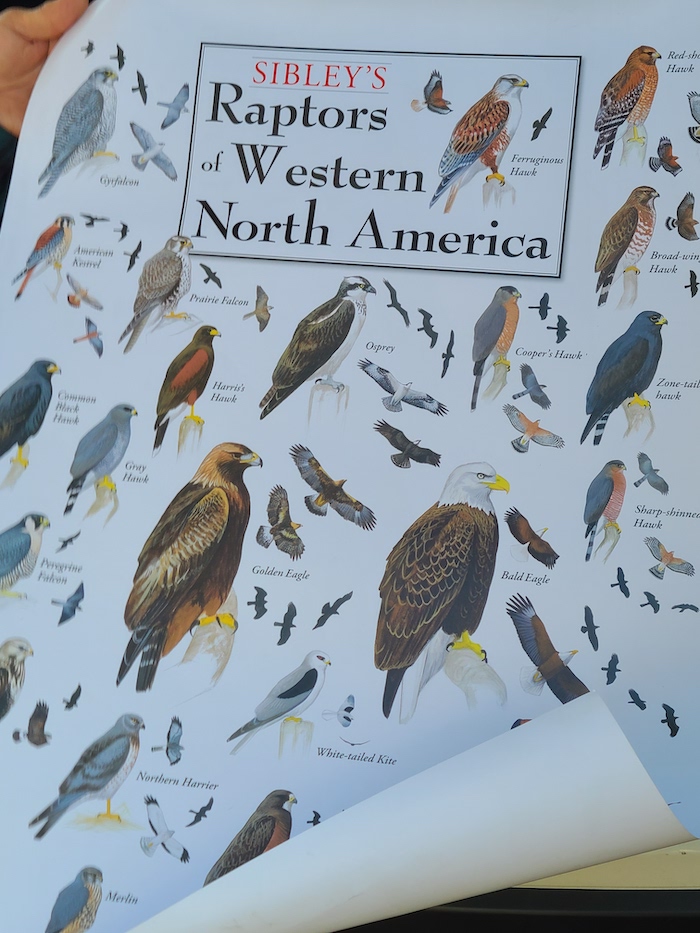

So, again, I thank Sonoma Land Trust for my most recent experience with kestrels. It was a successful day in the wetlands. As well as the American Kestrel, we had sightings of Red-tailed Hawks, Northern Harriers, White-tailed Kites, Sharp-shinned hawks, Peregrine Falcon, and a Merlin.