Download as PDF

4. The Vienna Connection

The trip to Dresden took over three hours on another bright and warm day, and the tour participants arrived at their destination during early afternoon. On the way, the tour guide lectured them on the present-day economy, culture, education, and politics of a unified Germany. After checking in at the Hotel Martha, the tourists walked over the river bridge to observe the reconstruction of a city that was in rubble after the Second World War. They visited such places as the Church of our Lord, the Zinger Palace, Opera House, and the Furstenzug Mural, before everyone was released to spend time on their own.

The following morning, the group departed for Prague, stopping on the way at the fortified town of Terezin that had been converted into a concentration camp during 1941. It seemed to Hilda that wherever she went, she could not avoid the history her parents lived through and survived.

During dinner in Prague, Hilda captivated fellow travelers with her stories from Berlin. They wanted to know more about the family connections with Vienna. She told them her father was born and grew up in the Austrian capital, was imprisoned for about eighteen months during the late 1930s, and after his release from prison, organized an escape to Shanghai for himself and Hilda’s mother at the beginning of 1941. It had been a harrowing time for her parents. They were required to visit the Central Office for Jewish Emigration, organized by Adolf Eichmann, to secure exit permits, and received them only weeks before the Nazi government banned all Jewish emigration. Her mother talked about being chased around a table by an expatriation official, but never knew what he wanted.

Hilda told her audience how her grandmother chose Vienna as the place to move to during late 1937, believing it was safer than Berlin and that it would allow her son-in-law to open a bookstore. Although he had a young wife and two infant daughters, there were other members of his family living in Vienna, and they would help take care of the four-year-old and the baby who had just turned one. At first, the family lived comfortably, pawning valuables they brought from their home in Berlin, but after Hitler invaded on March 12, 1938, these resources were quickly exhausted, and the son-in-law was detained in prison for selling illegal books. Anti-Semitism flourished in Vienna once Hitler arrived, as its citizens sought to destroy Jewish prosperity and force Jews to leave the country. The son-in-law’s family returned to Berlin with some of its relatives about a year later, leaving him in prison. Hilda’s grandmother and mother stayed in Austria.

During October 1938, Hilda’s father, Walter, was required to replace his Austrian passport with a German one, printed with a red “J” for Jew on the cover, alongside a swastika and a German eagle. According to Walter’s wife, he always refused to wear the yellow Star of David, and escaped to Shanghai before wearing it in public became compulsory.

About the same time in Vienna, Ellen received an invitation from her cousin, Gertrud, who she had played with as a child, offering to sponsor a visa for Ellen to move abroad to Britain. She declined, preferring to wait for her fiancé to be released from prison. As funds ran out, she moved to a Jewish orphanage where she lived and worked. At the same time, her mother was lodged in a care home and forced to scrub the streets of the city. She died penniless, grief-stricken, and broken-hearted on May 1, 1940, the same day that Ellen’s husband was released from jail.

Thereafter, Ellen lost contact with her cousin until after the war, when she learned Gertrud was living in London. Gertrud told Ellen that her own mother and an aunt and uncle had been deported during the war from Berlin to the Riga ghetto in Latvia, where they perished.

Hilda’s father was imprisoned for eighteen months but always said he was well looked after. The family speculated he received special attention from the guards because his deceased father was a well-known doctor who treated patients who could not afford to pay. During November 1939, prison officials accompanied Walter to City Hall where he married Hilda’s mother. Afterwards, Ellen returned to the orphanage and he went back to jail.

The reason why Hilda’s father was imprisoned was never announced. Allegedly he tried to smuggle valuables out of the country to help his mother relocate to New York after she remarried. Her new husband had relatives living in America who sponsored their visas. But charges were never filed. Hilda’s father was also a Jew and a journalist, both individually good reasons for imprisonment.

“He must have hated his home country?” someone asked.

“No, he didn’t,” answered Hilda. “In fact, he disappointed my mother by always loving his Austrian heritage. She hated Vienna and never forgave the people there for their treatment of Jews. She said it was a very sad time in her life and she cried a lot.”

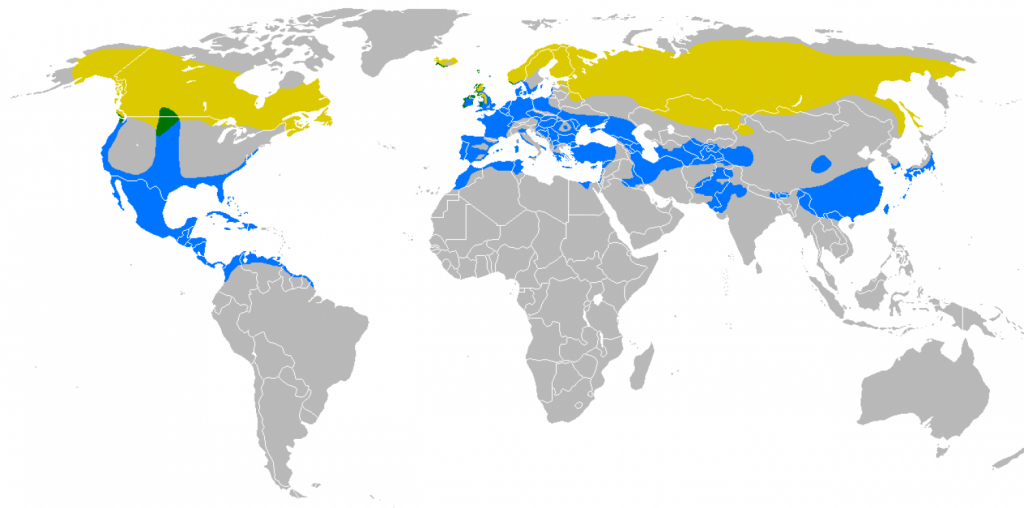

The conversation by now had turned somber, and the tour guide intervened to redirect the discussion to the topic he had assigned the group during the bus journey from Berlin to Dresden. He paired each person with a “buddy” and asked everyone to discover three things of interest about their partner. Two would be true and one false. Each person was asked to present, and members of the group would try to identify the story that was false. Hilda volunteered herself as a dancer, dog lover, and cosmetics salesperson; the last activity was not true. John put forward bird watching, architect and author, with the middle one made up. It was late in the evening before the quiz was over.

As Hilda returned to her bedroom, a travel colleague asked what had happened to her grandmother’s other siblings. “I’m not sure,” she replied. “I believe a brother died due to medical conditions, a sister disappeared and turned up in the United States after the war, and the youngest child, a brother, escaped to Shanghai.”

A few days later, after an overnight stay in the Czech town of Cesky Krumlov, the tour group arrived in Vienna. As with Berlin, it was Hilda’s second visit to the city, the first being with her mother during the early 1990s. She was shown the city but could not remember much about it. She knew from her parents’ passports that they left Austria during early February 1941, with travel visas allowing them to pass through Germany, Poland, Lithuania, the Soviet Union, Mongolia, Manchuria, Japan, and curiously, into Santa Domingo, the capital of the Dominican Republic. There was a currency stamp in her father’s document permitting him to carry a small amount of German Reichsmark.

Her parents never told Hilda why they ended their journey in Shanghai. Travel papers suggested their ultimate destination was the Dominican Republic. The Asian route was far safer than sailing across the Atlantic with its U-boat risks. Maybe they met people in Shanghai they knew. Whatever their reason, their departure from Austria was just in time. Hilda read about the mass railway deportations from Vienna that began a few days after her parents left the country. Within eighteen months, forty-five thousand Jewish men and women were deported to ghettos, extermination camps, and killing sites. Hilda’s mother heard after she left Austria that the children in her orphanage were killed.

Hilda recalled that the most memorable event from her first visit to Vienna was while traveling with her mother on a trolley bus. Several elderly passengers started to scold a group of misbehaving children. Her mother scowled and whispered to Hilda that it was the adults who should be scolded and be ashamed of their treatment of Jews many years earlier.

Hilda enjoyed the sightseeing during the two days in Vienna. With her travel colleagues, she visited the Vienna State Opera House, the Museumsquartier, Belvedere Palace, St. Stephens Cathedral, and Schoenbrunn Palace. At the end of the two days, it was time to say farewell. Her friends wished her success with the investigations, and a Canadian collected everyone’s email with the promise to circulate the list after he returned home. Unfortunately, the list never arrived. Hilda booked an extra three nights in the hotel and resumed her family inquiries.

Her first goal was to locate the apartments her father and mother had lived in before they were married. Addresses were on their marriage certificate and she was surprised how easy it was to find them. They were drab buildings with unremarkable architecture. There seemed no point in trying to enter.

The following day, she visited several research organizations to see if she could discover records about her father’s family. She had no success. No one seemed interested. It was as if the people she spoke to had forgotten what happened during the Second World War in Vienna, and were not eager to be reminded.

On the final day of the vacation, Hilda and John took the train to Salzburg to hear about another Jewish family who had been displaced just before the war, the von Trapp family. The difference was these people had reached the United States, not Shanghai, and were given care and protection. It was the best day of Hilda’s stay. The scenery was fabulous, the town of Salzburg charming, and the local Sound of Music landmarks exhilarating. She even enjoyed the sing-along on the tour bus with the escort dressed in his lederhosen.

But now it was time to return to San Francisco. The sightseeing had been enjoyable, celebrating her birthday at the Vienna Opera was memorable, and discovering the winery on the outskirts of Vienna that she thought her mother took her to visit many years earlier was unforgettable. She was disappointed the Austrian people generally acted aloof, and appeared uncaring and unwilling to admit their country’s involvement in National Socialism. To them, it apparently never happened. They were “occupied” by the Germans, and like many other parts of Europe, claimed they were not guilty of anti-Semitism.

By contrast, the Berliners acknowledged the actions of their ancestors and consistently tried to be helpful. Her confidence speaking German had improved, she had learned how to prepare the wiener schnitzel that her mother cooked for her, and she created several new friendships among the tour group. Most importantly, she was confident that the lady at the Charlottenburg Land Register would deliver on her promise. She would be patient; it was only two weeks since the visit to the District Court, and soon she would learn about the years her family owned the property that she had gazed at in Berlin.

European kestrel

European kestrel Sparrow hawk

Sparrow hawk Merlin eggs

Merlin eggs