Ridgway’s Rail

(Photo Credit eBird)

Some people hold the opinion that the saying “As Thin as a Rail” derives from a comparison with the skinny and slender shape of birds known as Rails, including the Ridgway’s Rail. Many of these species have laterally compressed bodies, which from the front make them appear thin, but from the side they look full-bodied. This unusual form permits each bird to pass easily through thick vegetation that grows in freshwater and saltwater marshlands. The alternative opinion is that the maxim refers to the more mundane wooden rail, stick, or bar used in the construction of fences. Etymology suggests that the bird took its name from the Latin and Old French word “rascula” that means “to rail” or “to mock”, and is likely a description of the hoarse vocalizations that these birds make. The Latin word “regula” is probably the source of “As Thin as a Rail” since it translates as “a straight stick”. Whichever is correct, this month’s Bird Blog features representatives of the Rail family of birds, and two species in particular that I am familiar with – the fairly abundant Water Rail in Europe and the very rare California Ridgway’s Rail in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Thin-as-a-Rail

Thin-as-a-Rail

(Photo Credit Lonely Birder)

Back during 1960, I recorded my first sighting of the elusive Water Rail. I do not recall its location but the most likely place was Fairburn Ings in the West Riding of Yorkshire, England. Back then, the site was an enormous slag heap of mining waste overlooking an area of open water and marshland created by ground subsidence caused by underground coal extraction. While the location was not a bird sanctuary until later that decade, I found it accessible for my childhood birdwatching. “Ings” is an Old English word to describe an area of water meadows and marshland.

European Water Rail

European Water Rail

(Photo Credit Encyclopedia Britannica)

Water Rails are hen-sized birds, about 9 to 11 inches (23 to 28cm) long, with chestnut-brown upperparts mottled with a black pattern, gray underparts and face, black-and-white barred flanks, and a mainly reddish- orange, long bill, used to probe mud and shallow water in search of food. The plumage affords excellent camouflage during the breeding season, and in winter, while the birds are potentially more visible, they skulk among the reeds and generally stay hidden. You are more likely to hear them emitting their pig-like grunts and rasping calls, than to see them. Also, as with other species of rail, they are rarely seen in flight preferring to move significant distances only under the cover of darkness.

Currently, it is estimated there are about 4000 breeding pairs in Britain, primarily distributed in the eastern region of England, and in winter they are joined by birds that migrate from Central and Eastern Europe. Western European Water Rails generally are sedentary thanks to the warmer weather. Conservation-wise, the species is considered of “Least Concern”, with a stable population in the UK, although their numbers are at risk due to flooding and freezing, habitat loss, and predation. The Water Rail population in Europe is estimated at around 700,000 birds.

European Water Rail Range Map

European Water Rail Range Map

Green – resident; Blue – winter; Yellow – summer; Orange – passage.

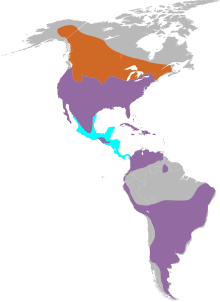

(Photo Credit Bird Field Guide UK)

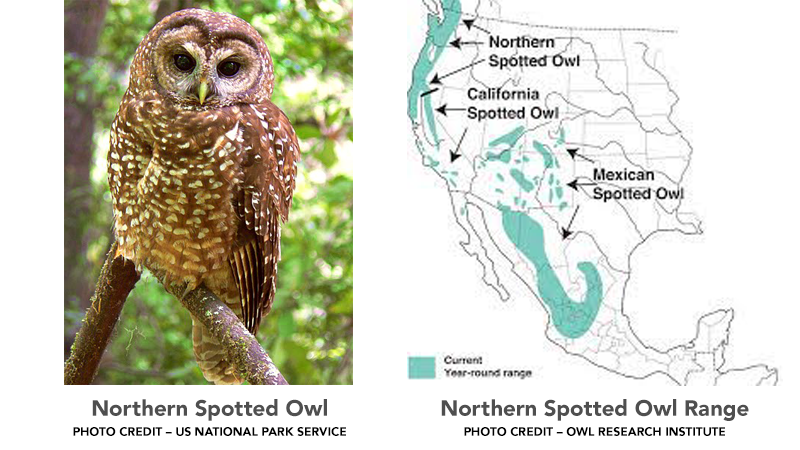

Move the clock forward about 60 years to last month when I had the satisfaction of sighting my first of another type of rail – the California Ridgway’s Rail. Prior to 2014, it was called the Clapper Rail, but following genetic research, this species was split into three regional groups, one known as the Mangrove Rail inhabiting the east coast of South America, the Clapper Rail that inhabits the US East Coast and Caribbean, down to Central America, and the Ridgway’s Rail for those resident in California, Arizona, Nevada, and along the western coast of Mexico. All three species are secretive wetland birds, the size of about a chicken, and are known for their loud rattling and chattering calls. The Ridgway’s Rail has been further separated into three subspecies, with the name of Light-footed Ridgway’s Rail given to birds in Southern California and Mexico, the Yuma Ridgway’s Rail to those found in the lower Colorado River and salty waters of the Salton Sea, and the name of California Ridgway’s Rail to those in the San Francisco Bay Area.

East Coast Clapper Rail

East Coast Clapper Rail

(Photo Credit Audubon)

Mangrove Rail

Mangrove Rail

(Photo Credit iNaturalist)

In addition, there is the King Rail, the largest bird in the rail family, at 15 to 19 inches (38 to 48 cm) in length, and one which is widely distributed throughout the eastern half of the United States. It prefers freshwater habitats. Also, in 2014, the Aztec Rail, about two inches smaller than the King Rail, was spun off from the King Rail as a separate species, and is resident in Mexico’s interior freshwater marshes.

2014 Introduction of new rail species

2014 Introduction of new rail species

(Photo Credit SF Bay Wildlife Society)

King Rail

King Rail

(Photo Credit Cornell Lab. of Ornithology)

Not shown on the above map is the distribution of the smaller rails which are native to North America. There is the Black Rail, a very rare and elusive bird, and difficult to spot because of its color. It is a mouse-sized representative, found in the southeastern coastal parts of the United States and interior sites, plus California. Its population is approximately 50,000, and of these, about 5,000 live in California primarily among the marshes of the northern Bay Area. The Virginia Rail, about 10 inches (25 cm) long, is more widespread and has a presence in northern California, the Central Valley of California, and the San Francisco Bay area. Finally, the scarce Yellow Rail, which is about six inches (15cm) long, breeds in Canada and winters along the Gulf Coast. A small population is present in California during winter, particularly in central California and along the coast.

Black Rail

Black Rail

(Photo Credit Travis Lux)

Virginia Rail

Virginia Rail

(Photo Credit Wikpedia)

Yellow Rail

Yellow Rail

(Photo Credit Cornell Lab. Of Ornithology)

But now let me address the California Ridgway’s Rail. It is 13 to 19 inches (33 to 48 cm) in length and named after Robert Ridgway, an important ornithologist during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, who for 40 years, was the Curator of Birds at the Smithsonian Institution. Among his many accomplishments was describing the taxonomy of the birds that now bear his name.

Like other species, the California Ridgway’s Rail is highly secretive and lives concealed among cordgrass, pickleweed, and saltgrass growing in salty and brackish water along the San Francisco Bay estuary. These birds are non-migratory. Over decades, large segments of the species’ habitat have been lost to urban development and in-filling, and as a result, by the 1970s, the bird was declared “endangered”. Today its population hovers around 1,100, and the majority live in wildlife refuges and ecological reserves, including the newly-restored four acre tidal wetland near my home that is part of the over 200 acres of salt marsh known as the Corte Madera Marsh Ecological Reserve. It is situated across from San Quentin Prison and the Larkspur Ferry Terminal, and during construction, non-native vegetation was replaced with around 17,000 salt-tolerant native seedlings.

Corte Madera Ecological Reserve

Corte Madera Ecological Reserve

(Photo Credit Corte Madera Memories)

On a Sunday during March this year I was walking along the loop trail at low tide when a flock of what appeared to be Western Meadowlarks flew in and settled in the grass, maybe 20 yards (18 meters) away from me. I wanted to confirm the identification through my binoculars. As I looked, there was no sign of the Meadowlarks, but suddenly a larger bird’s head and body popped up above the grass, giving the appearance on wanting to know “what is happening around here?”. By the time I comprehended what I was looking at, it had vanished into the grass, and I lost the opportunity to take a photo. It was a hansom grey bird, with a pinkish breast, and a whitish rump patch that was not visible to me. The shape was what you would expect, and its long, prominent bill was clearly seen.

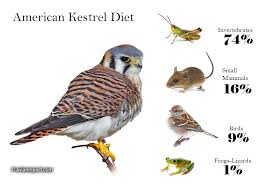

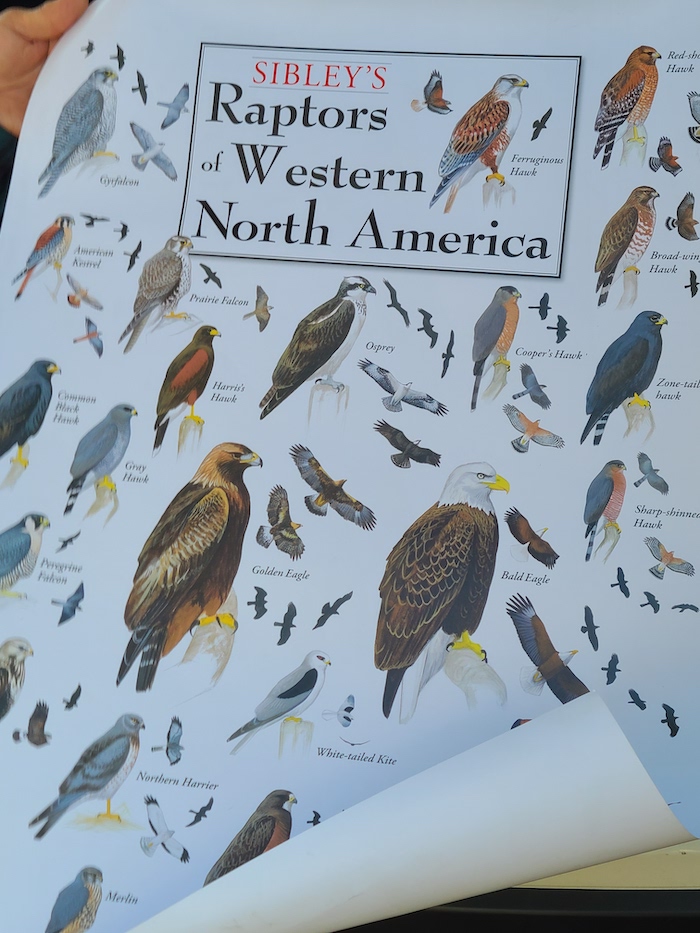

California Ridgway’s Rails forage by probing into muddy wetlands in search of invertebrate prey and prefer to inhabit areas with tall plant material that gives them protection. A special salt gland is used to drink seawater, and nesting usually takes place from mid-March to August. An average of seven eggs is incubated, and both partners share in the incubation. Once the chicks are hatched, they will leave the nest in a couple of days and may be carried on the backs of their parents during their first two weeks to help them survive high tides and to cross open water. The chicks are vulnerable to predatory fish, and the adults are preyed on by raptors, owls, foxes, and feral cats.

California Ridgway’s Rail with Young

California Ridgway’s Rail with Young

(Photo Credit Cornell Lab. of Ornithology)

I feel honored to have observed this species in their natural habitat and hope that their present numbers will at least be sustained. Not only are they vulnerable to loss of habitat, but rising sea levels offers them a new threat.

Hopefully, you have found my description of this family of birds at least of interest, if not useful. However, I would be remiss if I did not mention the most abundant and wide-spread rail in North America. It differs from other species in that it possesses a uniquely short and conical lemon-yellow colored bill and black face, and goes by the name of Sora rather than Rail. It can be found in freshwater marshes, including at the edges of water, and can be seen by me close by at the Las Gallinas Sanitary Ponds in San Rafael. The origin of the name is unclear but most likely comes from a Native American word, although no one knows which language and which indigenous people.

It is a small, chubby, highly secretive and stealthy, chicken-like bird (8 to10 inches/20 to 25 cm long). Most of its reproduction occurs in the north-central United States and Canada although, for winter, it migrates long distances, and flies as far south as Central and South America. Some pass through California, and there is a small resident population of Soras across the north and center of the state in places where suitable habitat exists. Its call is distinctive, either a high-pitched shout of “your-it, your-it” or a fast horse-like whiny. I hope to see one soon.

Sora

Sora

(Photo Credit Audubon.org)

Finally, I acknowledge that this family of birds may seem a little daunting to you, not least because of the many species (there are 152 species worldwide in the avian family of Rallidae), and most are difficult to see because of their size, and their skulking and secretive behaviors. Maybe consequently they have not attracted much attention other than those varieties that face extinction. This could be the reason why I overlooked this family of birds when I published my novel She Wore a Yellow Dress.

Azores Bullfinch

Azores Bullfinch

Photo Credit – avianreport.com

Photo Credit – avianreport.com

Turtle Dove

Turtle Dove Eurasian Collared Dove Range Map

Eurasian Collared Dove Range Map Mourning Dove

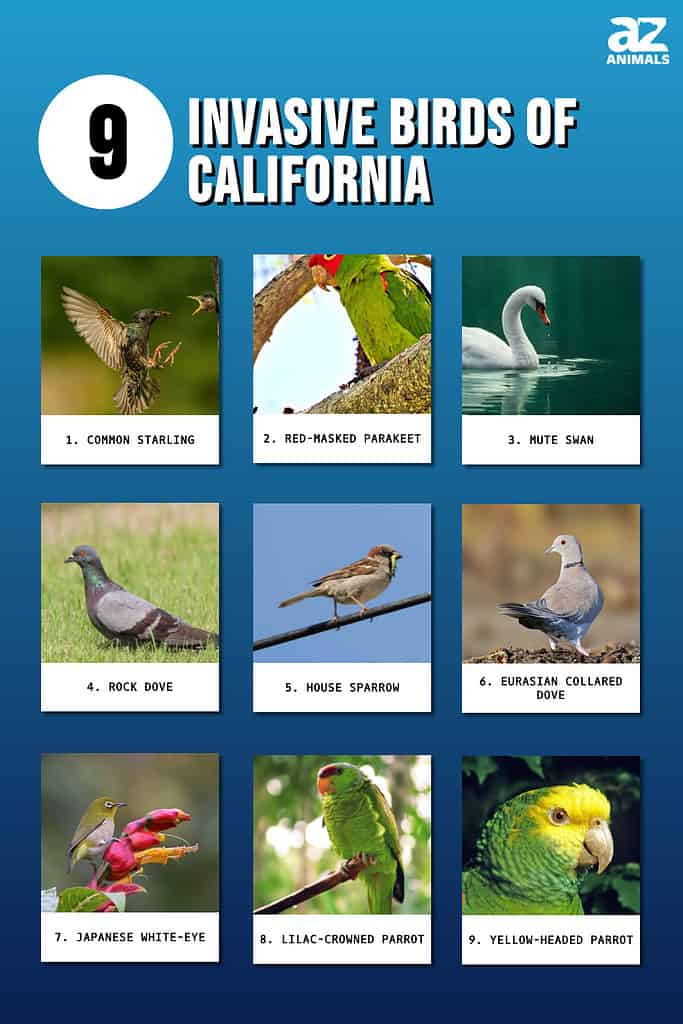

Mourning Dove Nine Invasive Birds of California

Nine Invasive Birds of California

Barn Owl Distribution

Barn Owl Distribution

Thin-as-a-Rail

Thin-as-a-Rail European Water Rail

European Water Rail European Water Rail Range Map

European Water Rail Range Map East Coast Clapper Rail

East Coast Clapper Rail  Mangrove Rail

Mangrove Rail  2014 Introduction of new rail species

2014 Introduction of new rail species  King Rail

King Rail Black Rail

Black Rail  Virginia Rail

Virginia Rail  Yellow Rail

Yellow Rail  Corte Madera Ecological Reserve

Corte Madera Ecological Reserve  California Ridgway’s Rail with Young

California Ridgway’s Rail with Young  Sora

Sora