Coming to Terms with Terns

One of the very few families of birds that remained constant when I moved from England to California in 1979 was the family of terns. I regularly saw Sandwich, Arctic, common, black, and little terns during my visits to Spurn Point in Yorkshire, and during 1971 I made a pilgrimage to Strangford Lough in Northern Ireland to see Sandwich, Arctic and common terns nesting. The latter is detailed in chapter 29 of my novel She Wore a Yellow Dress. They were extremely rare around my home town of York although passage Arctic terns occasionally showed up. Most members of this family are long distance migrants, moving between the northern and southern hemispheres when the seasons change. When I moved to California, sandwich, arctic and black terns were still present, the little tern was renamed the least tern, and new members included the Caspian, elegant, royal, and Forster’s terns.

Related to seagulls, terns are classified under the bird family, Laridae, and although similar in appearance to gulls, they have long swept-back wings and forked tail. They are usually identified by their deep rowing flight pattern and quick turns and hovering in pursuit of fish. They can dive vertically into the water from 20 to 50 feet (6 to 15 meters). Additionally, terns have straight, sharply-pointed bills, whereas gulls possess a more hooked one.

Sandwich terns

Worldwide, there are close to 40 species of terns, usually colored black and white, although in most cases, more white than black. To the casual beach goer they may look alike. The best way to distinguish between species is to note their size, the color of their bill (red, orange, yellow, or black), the existence or otherwise of blackish wing tips, and the length of their tail streamers. Additionally, the elegant, royal and Sandwich terns display a ragged crest on the back of their heads, especially noticeable during the breeding season.

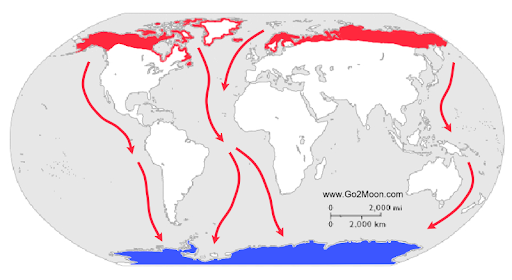

Most importantly, terns are known for the great distances they travel, especially the Arctic tern that breeds during summer in the Arctic and migrates south for winter to Antarctica. They each can travel around 25,000 miles (40,000 km) annually, gliding as well as flying, usually out at sea, and taking around 40 days for a one-way migration.

Arctic tern migration map

During my years living in Northern California, I have watched the fishing antics of the common tern, the Forster’s tern, the Caspian tern, and the elegant tern. Some varieties breed locally and others, like the common tern, are visitors during migration. The one species of tern that eluded me for many years was the least tern, the smallest of all terns, about the size of a large songbird. They breed in small numbers in the San Francisco Bay Area, but because of their endangered status, they are subject to close protection.

Least tern

Least tern Range Map: orange – breeding; blue – non-breeding

The least tern is distinguished by a distinct white patch on its forehead, interrupting its otherwise solid black cap, and in summer has a yellow bill with a black tip, and yellow feet. It usually flies low over the water with quick deep wing beats and a hunched-over look, and shrill cries of “kellick” or “kip-kip-kip”, often heard just before it is seen plunging into the water after its prey. The species nests in colonies, usually around 25 pair per colony, scratches out a “scrape” in sand or gravel on the beach, and lays three green eggs blotched with brown.

Next and eggs of least tern

So you can imagine my excitement when, at the start of August 2021, while on vacation in San Diego County, I discovered that least terns were nesting only a few miles away, close to the Mexican border, under the protection of the Tijuana Slough National Wildlife Reserve. It was a dull, cool, Friday morning as I and my friend drove south for about 30 minutes, before arriving at Imperial Beach, where we quickly located the Reserve’s Headquarters. We were greeted warmly and offered abundant advice. Immediately, I was told that Bewick’s wrens, scrub jays, dark-eyed juncos, bushtits, song sparrows and Anna’s hummingbirds had been seen close to the Reserve’s building that morning. However, we were soon on our way across the marsh to see what we could see, along with the accompaniment of the sound of helicopters from the nearby helicopter base. In the distance was Tijuana, and the US – Mexico border wall, undulating along the hills and eventually running down to the beach and into the Pacific Ocean.

Tijuana Wildlife Reserve

Almost immediately there were juvenile black-crowned night herons waiting to catch fish, and black phoebes fluttering in search of insects. Other bird species we recorded during our walk were the American kestrel, northern harrier, marbled godwit, cliff swallows, northern mockingbird and a Forster’s tern fishing in the tidal lagoon, but no sighting of a least tern.

Forster’s tern

The warden commiserated with us back in headquarters, and told us to visit the beach to the south of the town. At first we encountered several groups of large, stocky shorebirds, called willets, searching for food at the water’s edge, and could see several types of terns fishing out at sea, mainly elegant terns and one large Caspian tern.

However, just when we were about to give up on our search, we heard overhead the cry of “kip-kip-kip”, as two least terns passed us by. They are closely related to the Old World little tern, but are treated as a separate species based on voice difference. I had achieved the purpose of our journey.

Willet

As for the fate of terns, their numbers and enormous range offers them some security although for several species their numbers have dropped. They suffer loss of habitat from development and disturbance and from predators. Longer time, climate change presents a major threat. The Arctic tern that follows the summer season between hemispheres is at risk of losing up to 50 percent of its natural habitat due to global warming.