Dark-Eyed Juncos: Birds that Frolic in the Winter Rains Brought to California in Atmospheric Rivers

Dark-eyed Junco in my Backyard

Photo Credit: The Author

The species of bird known as the Dark-eyed Junco appears to be the only bird willing to forage among my Bay Area backyard bird feeders during this winter’s torrential downpours. While other birds hide in the trees and among the bushes, small groups of Dark-eyed Juncos can be seen, undaunted by the weather, greedily feeding on the seeds that overspill under my bird feeders, as well as taking seeds directly from the bird table. When the heavy rains start, Goldfinches and House Finches quickly find shelter, Chestnut-backed Chickadees suspend their visits, and the more aggressive birds such as California Scrub-Jays and American Crows disappear until the storm has passed. Even the Oak Titmice and Bewick’s Wrens appear to delay searching for food when the deluge begins. The Mourning Doves have long since moved south, and the California Towhees (large brown sparrows) have insufficient dry leaf litter to scratch to make a trip to my backyard worthwhile.

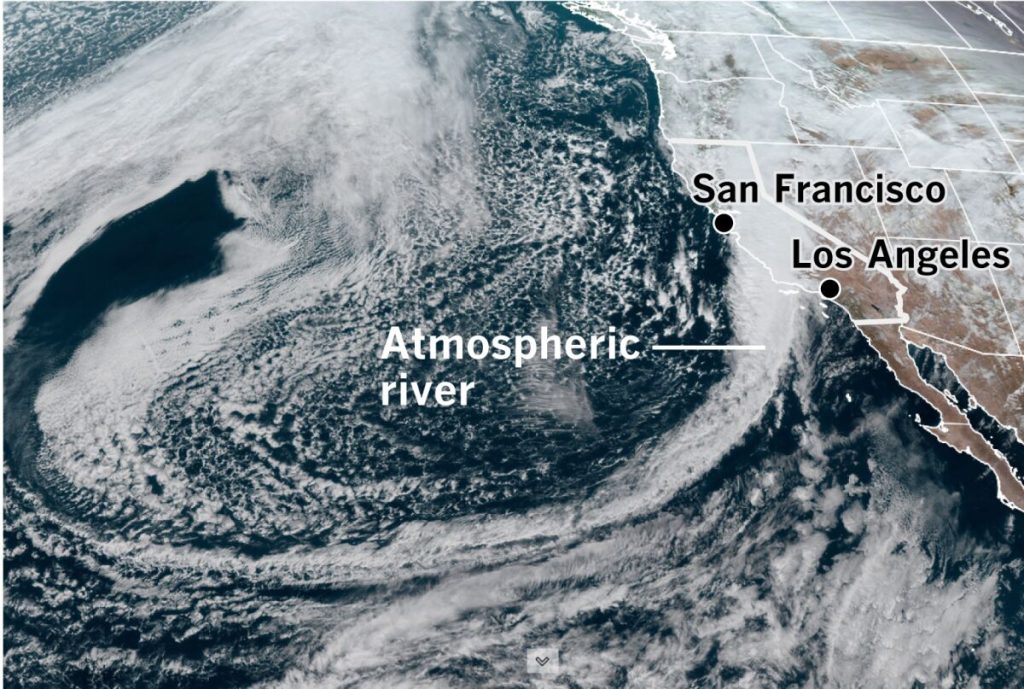

These increasingly frequent storms – previously known as Pineapple Expresses – are now called “atmospheric rivers”, a term introduced by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology during the 1990s to describe long, narrow, plumes of water vapor, usually originating in tropical areas that bring torrential rain to the west coasts of North America and northern Europe. My local news station today uses these power words to warn me of imminent heavy rain, and the possibility of flooding, falling trees, and landslides.

Photo Credit: Cornell Lab of Ornithology

Atmospheric Rivers were assigned five rating categories in February 2019.

- AR 1: Weak (primarily beneficial)

- AR 2: Moderate (mostly beneficial but also somewhat hazardous)

- AR 3: Strong (balance of beneficial and hazardous)

- AR 4: Extreme (mostly hazardous but also beneficial)

- AR 5: Exceptional (primarily hazardous)

Most bird species continue their normal activities during light rain because of their need to eat frequently, and they waterproof their feathers through the action of preening. There is a special uropygial gland at the base of the tail of many birds that produces a waxy oil that is used to preen the bird’s feathers. If it rains too hard, however, and especially if the rain is accompanied by strong winds, birds typically will seek shelter. Otherwise they risk flying into objects or can be hit by twigs, trash, and other materials. Most land birds are sensitive to temperature change but studies show that Dark-eyed Juncos respond physiologically to changes in the duration of daylight, and thrive in the cold.

As a result, at the peak of a storm, I often see small flocks of Dark-eyed Juncos flitting along the ground, hop-hopping (not walking), and pecking at the ground looking for seeds. They sometimes are aggressive towards each other but become more mild-mannered in relation to other bird species. Those arriving first rank themselves higher than those arriving after them, and are not shy in demonstrating their “I was here first” attitude. There is a definite pecking order, with females often on the lower rungs of the hierarchy.

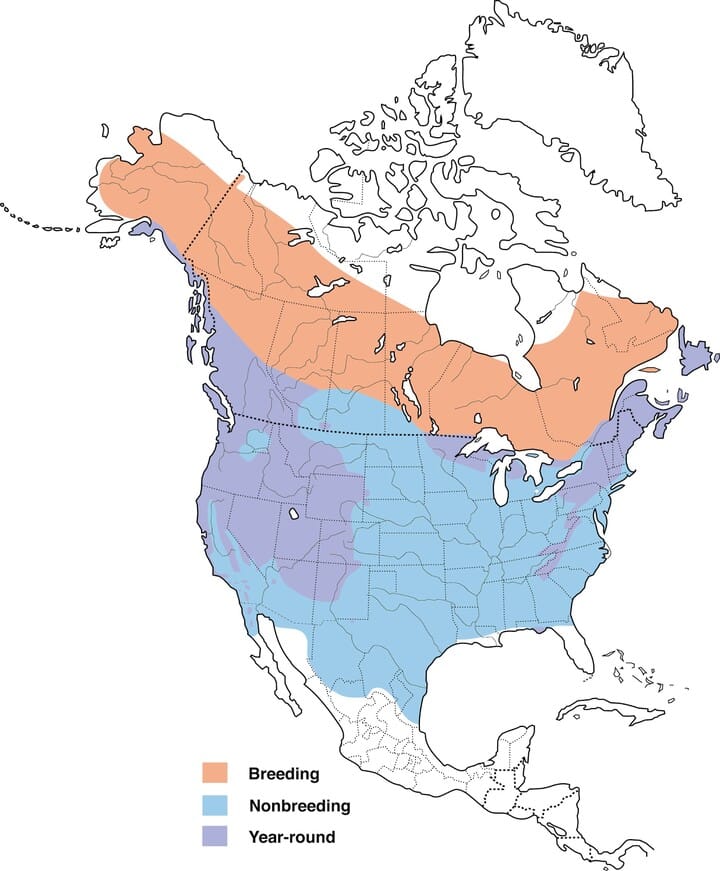

Dark-eyed Junco Range Map

Photo Credit: Cornell Lab of Ornithology

Dark-eyed Juncos are one of the most common birds in North America and are found across the Continent, from Alaska to Mexico, and from California to New York. Population estimates vary, with current projections of 220 million breeding birds, despite a 30 percent decline in numbers during the past few decades. The name Junco is taken from the Latin word iuncus or juncos, meaning rush or reeds, presumably the habitat close to where the bird was first identified and given its official name. In North America, there are two species of Junco, the dark-eyed variety, the subject of this report, and the Yellow-eyed Junco whose range is restricted to Mexico and the southern parts of Arizona and New Mexico. The population of the Yellow-eyed Junco is around 20 million.

Yellow-eyed Junco

Photo Credit: Cornell Lab of Ornithology

Dark-eyed Juncos are a medium-sized sparrow, native to North America, and display a rounded head, small pale bill, and a fairly long, conspicuous, tail, with white outer feathers that periodically flash open particularly in flight. The color of their plumage varies by geographic region, with about 15 sub-species identified and grouped into five major categories: Grey-headed, Oregon, Pink-sided, Slate-colored, and White-winged. In the West, it is the Oregon variety that is usually seen, with its black to dark gray head and brown back and sides. East of the Great Plains the dominant representative is the Slate-colored Junco. In 1983, the American Ornithological Union declared that despite these regional differences in plumage, only two species of Junco exist: the Dark-eyed Junco and the Yellow-eyed Junco.

Dark-eyed Junco: Slate-colored variety

Photo Credit: Cornell Lab of Ornithology

Dark-eyed Juncos are one of the most abundant forest birds during summer to be seen nesting on the ground, often using banks and steep slopes that are covered in vegetation to hide their nests. They breed in the mountains of Canada and Alaska, the western United States, and the Appalachians. Some birds remain resident during winter but many migrate medium distances, either southwards or vertically to lower altitudes.

Nesting Dark-eyed Junco

Photo Credit: Damon Calderwood

In England, during my early days of birdwatching, the idea of spotting a Dark-eyed Junco never occurred to me. They are considered to be American vagrants over there. The first recorded sighting of this species in Britain was as recent as May 1960, and since that date, only about 45 other occurrences have been reported. Typically these sightings involve the Slate-colored variety that populates the eastern side of North America. Many other birds I saw back in the 1960s are described in my novel She Wore a Yellow Dress.

So why does this member of the sparrow family take center-stage in my American backyard during winter, and especially during periods of heavy rain? For decades, it has been considered as the harbinger of winter and given the nickname of “snowbird”. They are energetic birds, constantly on the move, and are not deterred by swirling rain and snow. While other birds hide, expect to see these birds out in the garden foraging during Atmospheric River events. And as the hours of daylight change, expect them to prepare for migration to their breeding grounds, and due to their current high numbers, they remain of “least concern” from a conservancy point-of-view.

Known as Snowbirds because of their habit of appearing at bird feeders during winter

Photo Credit: Unknown