The Rise and the Fall of the European Starling

Here is the story of a species of bird that has flourished on continents where it was introduced during the 19th century while at the same time suffering serious decline in its native Europe.

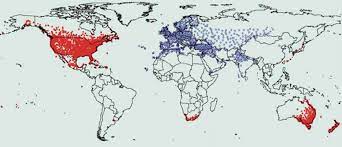

In North America, there were close to 200 million European starlings a few years ago, dispersed from Alaska to Mexico, with geographic extensions into Puerto Rico, Jamaica, and Cuba. Most are descendants of approximately 100 starlings released in New York’s Central Park during 1890 and 1891 by a group of people dedicated to introducing bird species mentioned by Shakespeare in his plays. Their territory rapidly expanded due to the species strong flight ability, its adaptability to various habitats, the production of two broods each season, their aggressiveness, and their diverse dietary choices. The average life span is two to three years but individuals can live up to 20 years.

As early as 1914, people in the United States realized how harmful these birds could be and efforts were made to discourage them. For example, in parts of Connecticut, residents tried to scare them away by fastening teddy bears to trees occupied by the birds, and fired rockets through the branches.

Red coloring – European starling introduced Blue coloring – native habitat

By 1928, European starlings had reached the Mississippi, and in 1942 they had made their way to the West Coast. Today, these birds are regarded as pests and their numbers are supposed to be in decline. Estimates in recent years are that the North America population has decreased to around 140 million.

The United States classifies the species as invasive and does not protect it under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act. As a consequence, hundreds of thousands of starlings are killed each year. The US Department of Agriculture reports eliminating 1.5 million birds during 2012 and about 700,000 in 2019.The damage that these birds cause annually to North America agriculture is estimated at approximately one billion dollars.

The North America experience is repeated elsewhere. For example, in Southern Africa, the starling was introduced in 1897 around Cape Town and is now the most common bird in that region. In New Zealand, starlings were introduced in 1862 to destroy the hordes of caterpillars and insects that invaded newly planted crops, whereas today it is considered a pest by orchard owners and an advantage in pastoral areas. In Australia, the starling was introduced in the Melbourne area during 1857 to control insects that were invading farm crops, and rapidly spread across the south-east of the country. In Argentina, the European starling appeared first during 1987 in Buenos Aires and has rapidly expanded its territory.

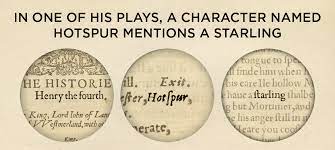

Shakespeare only mentions the starling in Henry IV, Act 1, whereas I refer to them twice in my novels. In Unplanned they forecast the weather, and in She Wore a Yellow Dress I feature their habit of flocking in flight during fall and winter to create acrobatic murmurations. They are permanent residents, although some will migrate short distances.

The seagull and the starling

Growing up in Yorkshire, England during the 1960s, I encountered starlings in most places, from around the farm to school grounds, and I also saw one attacked and drowned by a common gull at Spurn Point bird observatory. They received virtually no mention from my colleague birdwatchers because of their abundance. However, since I moved to the United States in 1979, their population in Britain has declined by an estimated 90 percent. The reasons are unclear but seem to include loss of habitat and the poisoning of the insects that they eat. Even so, there remains an estimated 1.8 million breeding birds in the UK, even though the species is placed on Britain’s red-list of birds that carry the greatest conservation concern.

European starling aggression

They are aggressive, stocky, social, and noisy birds that are medium-sized (about 8 inches/20 cm long – the size of an American robin), have short triangular wings, a short tail, pinkish red legs, and a long, slender, pointed bill that is yellow during the breeding season but becomes dark in the fall. They tend to walk rather than hop, and typically roost in trees and on telephone and power lines. During summer, their plumage is a dark, iridescent purplish-green, molting into a blackish-brown with feathers tipped in white to give the bird a speckled appearance. Starlings belong to the family that includes myna birds noted for their voice mimicking. The starlings own whistling and whizzing are sometimes a mimic of other starlings, and occasionally they will repeat the sounds of people, animals, and inanimate objects like police sirens.

Starling roost

European starlings are common in towns, suburbs, and in the countryside close to human settlements, where they forage for food on the ground. They are highly social and enjoy an evening singsong. Eating habits are omnivorous and include taking fruits, grains, and seeds, which has caused them to be treated as agricultural pests. The fact that they eat invertebrates, such as leatherjackets (the larval stage of daddy long legs) that damage the roots of grasses and crops, is often overlooked.

They also compete aggressively to secure tree cavity-space for nesting sites, and in North America displace native species such as bluebirds, oak titmice, acorn woodpeckers, and tree swallows. Starlings quite literally push out the native bird. Nesting in gutters and vents of buildings and competing aggressively at bird feeders have added to their notoriety, as do their messy droppings that can cause disease.

It is hard to mistake other birds for European starlings. The common grackle in North America is similar looking, but larger, and has a yellow eye whereas starlings have dark eyes. These grackles are resident east of the Rocky Mountains and their cousins, the great-tailed grackle, are present in southern California but look distinctly different. Other similar-looking birds in North America include the brown-headed cowbird and Brewer’s blackbird. In Europe, the nearest comparable species is the blackbird.

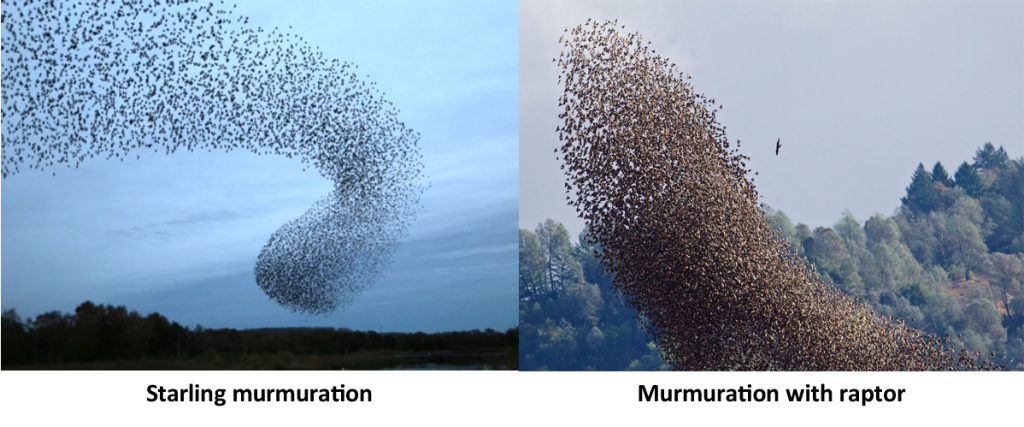

It is the winter’s evening entertainment of aerial displays known as murmurations that is the welcome side of starlings. These murmurations sometimes involve hundreds of thousands of birds and occur when they gather above their roost at dusk to fly in patterns before settling down for the night. The feature is particularly visible from October to February. Where does the name come from? The best guess is from the low and indistinct sound that the birds make in unison, particularly after they land, and is taken from the Latin “to murmur” or “to mutter”. These flocks of birds can be seen twisting, turning, swooping, and swirling across the sky in mesmerizing shape-shifting clouds. The behavior is believed to confuse predators and help the birds keep warm, and studies show that each bird follows the path of about seven of its closest neighbors. No other bird has a comparable aerial display, although dunlins, some sandpipers, American robins, red knots and geese can be seen traveling in flocks.

The starling may also have weather-predicting abilities. Like many birds, starlings possess a special middle-ear receptor known as a Vitali organ that detects extremely small changes in atmospheric pressure. As atmospheric pressure falls – indicating an approaching storm – the birds fly lower and lower and eventually roost to quietly await the arrival of rain. This weather forecasting ability, however, does not include long range forecasting!

Despite the entertainment value, the starlings’ reputation remains much more as a pest and they suffer from human persecution. They are frightened out of gardens because of aggressively occupying bird feeders, their nests are destroyed because of the inconvenience and their filth, and farmers shoot, trap, and poison them because of crop destruction.

Another feature of European starlings is that they are subject to mysterious deaths when up to hundreds of birds fall out of the sky and die. These incidents have been reported in the UK, the United States, the Netherlands, and Spain. There are stories of starlings tumbling from above and ending up dead on the road, in gardens, and across fields. The cause is a mystery and suggestions offered include that the birds were being chased by a bird of prey and hit the ground as they changed direction, or that they were reacting to a change in the weather, or that they had been poisoned. Tests usually show the birds died of physical injuries rather than from health causes. There are, however, incidents of birds flying too low and hitting moving vehicles, and drones causing chaos in the midst of murmurations.

European starlings – an invasive species

So what is the future of the European starling? Should these birds be protected, especially in the Old World where their numbers are in serious decline, or culled as in the New World where they remain an invasive species and a threat to agriculture and native birds? United States regulations allow their eggs to be taken as well as permitting their capture and lethal removal. In the Old World, people use scaring devices, shoot or trap the birds, and spray chemical repellants. In countries such as the Netherlands, Spain and France, starlings are sometimes eaten as food (for example, as pate de sansonnet).

It is a controversy that won’t be resolved anytime soon. Sadly, once upon a time, the European starling was a national treasure, a source of aesthetic beauty, and occupied an important role in agriculture. Today, thanks to the Agricultural Revolution, most of that has changed. The introduction of pesticides, the development of crops that are resistant to insects, mechanization, and the implementation of new farming practices, has replaced the need for the starling. The species now has a reputation as an invasive agricultural pest that carries disease to livestock and people.

In the meantime, I invite you to reflect on the starlings past history and consider the Legend of Branwen, the daughter of the King of all Britons. After marriage to the King of Ireland, she moved to Ireland where she was abused by her husband. She taught a starling to speak and had it fly to her brother to tell him of her plight. The bird succeeded in its task and her brother came and rescued her. Exactly whether or not this happened is uncertain, but the tale is believed to be based on real events that occurred during the Bronze Age of British history. Well done the European starling!

Last but not least, you may also be interested in watching the Netflix movie The Starling, recently released, and starring Melissa McCarty, Chris O’Dowd and Kevin Kline.