History of the Crow

Recently, I came across a glossy, all-black American crow removing fiber from the back of my outdoors lounge chair. It gave me a look of disgust and then resumed its destruction, presumably using the stuffing to decorate its nest some distance away. Both sexes look alike so I could not determine if the thief was male or female. Crows are smart, social, and resourceful birds, and nearly daily visitors to my California back yard. Often in family groups, they squawk incessantly, feed on whatever they can find, and fly from perch to perch for reasons that are unclear to me. They live in tight-knit family units, with young crows staying with their parents to help raise their younger siblings in future years. There are around 30 million of them in North America, although in recent years the population has been affected by the West Nile virus, a mosquito-borne pathogen that kills corvids more than any other species of bird.

Even so, the American crow population appears to be exploding, and today the bird is present in most urban and suburban settings, having learned to pick out safe situations and avoid dangerous ones. They are a lot smarter than they look. Records suggest that they spread westwards across North America as European settlers moved from east to west. Back then, they were often unwelcome guests because of their habit of foraging in cornfields and orchards. They were considered vermin and suffered unrestrained persecution through shooting, poisoning, and the destruction of their nests and eggs. In some cases, bounties were paid. An example was in the 1940s and 1950s when the US Federal government offered a bounty for each bird killed to protect the nation’s grain supply.

In the Old World, persecution of European crows has probably even been more severe over the centuries. Henry VIII in England passed the Preservation of Grain Act in 1532 in response to a series of poor harvests. The Act made it compulsory for every person in the country to kill as many crows as possible, along with other vermin such as weasels, stoats, hedgehogs, badgers, and foxes. Parishes raised levies to pay the bounty, and communities that failed to kill in sufficient numbers were punished with fines.

Supposedly, the meat of a crow is foul-tasting and the term “eating crow” is used for people who admit to humiliating mistakes and errors. Additionally, in Leviticus 11:15, God declares that “ravens of any kind” (the corvid family) should be regarded as unclean and never be eaten.

In the United States, prior to 1972, crows were shot or poisoned at will and denied protection under the 1918 Federal Migratory Bird Treaty Act. This situation was amended in 1972 when corvids were made exempt from hunting, but with exceptions for landowners to kill the birds if they believed they were damaging or threatening trees, agricultural crops, livestock or wildlife. Specific days were set aside for hunting the birds outside their breeding season, but only firearms, bows and arrows, and falconry could be used. California adopted this exemption and authorizes licenses and permits from December 5 to April 7, with a daily bag limit of 24 birds. Data on numbers killed is limited although, in 2015, hunters reported killing about 35,000 birds.

So, if you were an intelligent bird, where would you move for greater safety and protection – likely to either urban or suburban centers where shooting is not permitted? In addition to not having crow shoots, cities provide alternative sources of food, have a warmer climate, offer an abundance of trees for roosts, and supplies artificial light to help look out for predator owls. In the city of San Francisco, an estimated 122 crows were recorded in 2000, whereas today the number has risen to around 900.

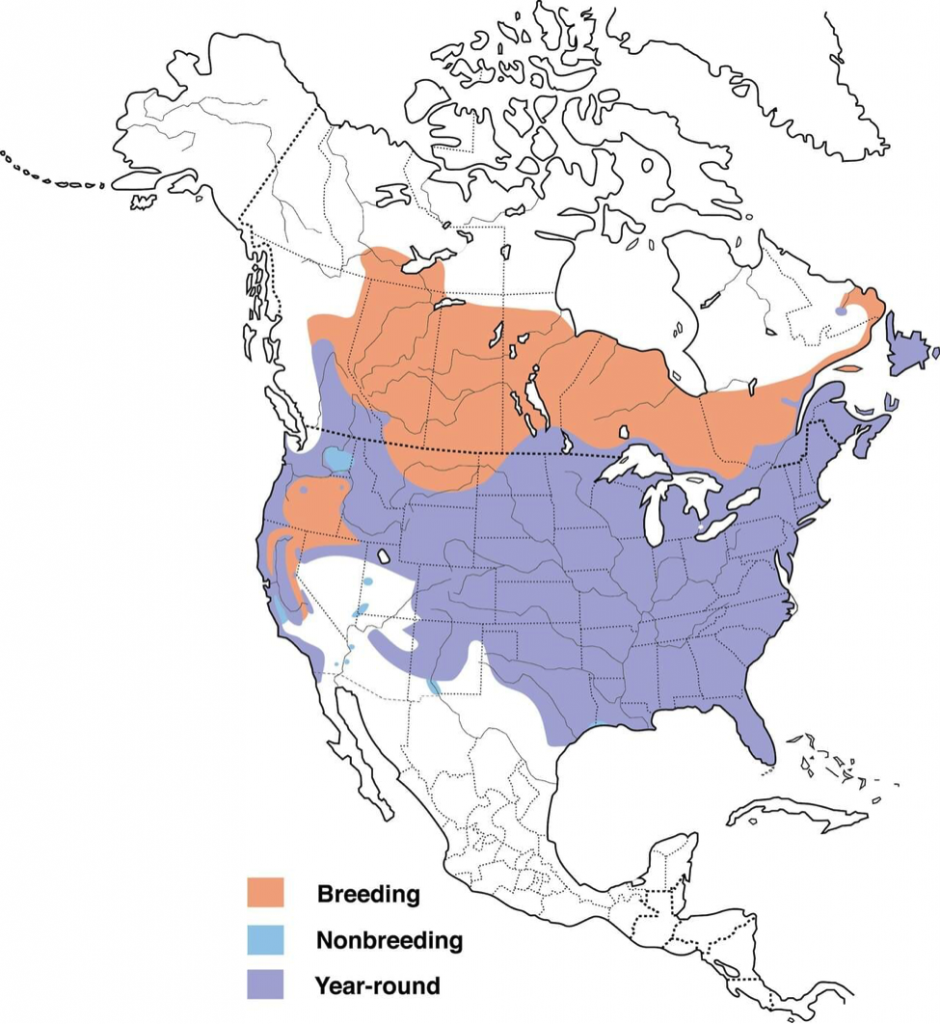

American crow Range Map

Crows remember their experiences and communicate them to others, they protect each other at night by roosting in tight-knit “murders” (a hunting term used since the 14th century for a group of crows), they problem-solve such as opening plastic bags, dropping nuts in front of cars to be driven over, soaking hard food items in fountains and bird baths before eating, and collecting and storing food for future use. They can recognize individual humans and behave hostile towards those that threaten them or come too close to their breeding territory.

They cluster in parks and gardens, scavenge and compete for food at dumpsters and bird feeders, and cackle whenever they choose, including early in the morning. They mainly feed on dead animals, fruits, seeds, grain and nuts, insects, amphibians, small mammals, shellfish, and the eggs and chicks of other birds. The latter habit causes offense among humans, although there is no evidence that it reduces the population of other species of bird. Increasingly, crows rely on humans and urban habitats for their food, safety, and the availability of nesting sites.

The American crow is comparable to the carrion crow and hooded-crow in the Old World, that I would see during the 1950s and 1960s. Some of these experiences are recounted in my novel She Wore a Yellow Dress. European crows display the same levels of intelligence and are equally as aggressive. For example, in parts of Berlin, crows have learnt to single out elderly ladies carrying plastic shopping bags as a likely source of food. More locally, here in California, crows will follow golf carts on the golf course, and look for food while the golfers are away conducting their sport.

The carrion crow is a glossy, all-black corvid, and fairly common across Western Europe. It was a resident around my rural home near York, England when I was a child, despite the habit of farmers erecting “scarecrows”, skinny decoys dressed in old clothes to resemble a human figure, to frighten away these birds. The ash-grey hooded crows were occasional winter visitors, but their numbers in Yorkshire have since declined.

The European rook is very similar to the American crow in that it is gregarious and prefers to live in tree-top colonies. They are relatively large black-feathered birds, distinguished from other corvids by the whitish featherless area on their face. So far, they appear reluctant to move into urban settings.

One of the greatest enemies of the American crow is the raven, a much larger and all-black bird, with large bill, wedge-shaped tail feathers (crows are fan-shaped), and a well-developed ruff on its throat. Its call is more of a croaking sound, or “gronk-gronk”, and unlike the crow, it is not common in populated areas. Where their habitats overlap, crows will attack their larger cousin to try and stop the latter’s habit of pillaging crows’ eggs and the young. They also engage in mobbing other birds when they believe their territory is under threat. On a quiet afternoon in California, you can hear the “caw-cawing” of a group of crows chasing high overhead after a red-shouldered or red-tailed hawk, and you can hear the hawk’s repeated “kea-oah” call as it tries to avoid being pecked to death.

In summary, American crows are uniquely adapted to cope with a changing environment and the increasing presence of humans. European corvids have done the same, but to a lesser degree. Along with sparrows, rock pigeons and starlings, crows are now the fourth “city bird”, but because of the mess and noise that they make and the false belief that the West Nile virus is spread by them, there is a desire to control their numbers. However, he simplest solutions are to keep crows out of trash cans (do not feed them) and discourage garden visits with netting and inaccessible bird feeders, rather than killing them. Remember, if you do menace crows, they can carry a grudge against you for a very long time to come, and communicate their dislike to others. The look I received from the crow that was stealing the stuffing from my chair suggested that was not yet on its enemy list.