Northern Wheatears, Champions of Migration

I was first introduced to Northern Wheatears at the end of March 1961 during a school geology fieldtrip to Stainforth in Ribblesdale, Yorkshire, England. A small group of us were studying the area’s Carboniferous Limestone and Millstone Grit and searching for fossils in the older Ordovician and Silurian outliers. It rained most of the time and the river flooded our camp site forcing us to return home early. However, on the last day before leaving, during a hike along a country trail in Crummack Dale, I encountered my first Northern Wheatear as it hopped along the ground in front of me flashing its prominent black and white tail pattern. I would later record large numbers of Northern Wheatears migrating through Spurn Point, Yorkshire.

Northern Wheatear in Crummack Dale

The Northern Wheatear is a small bird, slightly larger than an English Robin, and breeds in stony, upland areas of the North Pennines as well as on similar terrain elsewhere in western and northern Britain. Once procreation is complete, it migrates south to Africa for winter. The plumage of the male during the breeding season is grey on the upperparts, buff throat, and black wings and face mask. In the fall, it resembles the female except that it keeps its black wings. The female is plain brown above and buff below, with dark brown wings. Both sexes have a white rump and tail, with a black inverted T-pattern at the end of the tail.

Large numbers of Northern Wheatears travel way beyond Britain, across the North Atlantic, to Greenland and eastern Canada. I was thrilled by my first sighting. The species had only occasionally been seen by other birdwatchers around my home town of York, and mostly spotted close to the River Ouse, suggesting that these birds used the river to navigate their way northwards. As described in my novel Unplanned, the river is one of the routes used by the German Luftwaffe to bomb British inland cities during World War 2.

York and the Ouse

Do not be fooled by the Wheatear’s name, it has nothing to do with grain; the species eats insects not seeds. The name is derived from the Old English phrase “hwit aers”, meaning “white arse”, which refers to the bird’s white rump. In England during the 18th and 19th centuries the bird was considered a delicacy, and shepherds would supplement their income by selling the Northern Wheatears they trapped.

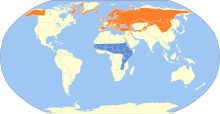

Northern Wheatear Range Map: orange – breeding; blue non-breeding (wintering)

The Northern Wheatear spends its winter in Sub-Sahara Africa and breeds throughout Europe and across the Palearctic regions of Asia, with footholds in northeastern Canada as well as in northwestern Canada and Alaska. During the fall migration, birds from Alaska and northwestern Canada cross the Bering Strait to Siberia and then navigate southwestward across ice, water, mountains and deserts, to the Caspian Sea, Iran, and Iraq, from where they cross the Red Sea to Africa, passing by Egypt, the Sudan, and Ethiopia, to arrive in such countries as Uganda, Kenya, and Northern Tanzania. Individual birds begin this annual round trip of up to 18,500 miles (30,000 km) in August, and travel for close to three months to complete the journey. They fly at night and cover, on average, about 180 miles (290 km) a day. They are believed to accomplish the longest journey of any songbird, and their chicks are born with the ability to independently navigate these thousands of miles.

Birds from eastern Canada migrate via Greenland and Europe to winter in West Africa, from Senegal and Sierra Leone east to Mali. Some pass through Britain but many appear to head directly across the ocean to Portugal and Spain from where they cross to Africa. Why these North America breeding birds fly to Africa, and not to Central America, like other birds that nest in Alaska and Northern Canada, is unknown. If an egg is removed from an Alaskan nest and taken to Eastern Canada, the chick will still fly westwards across Canada to Asia.

Northern Wheatear Migration Flight-ways

Today, Britain has approximately 240,000 breeding pair of Northern Wheatears, and the worldwide population is estimated at as many as 125 million. About 40 million breed in Europe, where the population is showing a moderate decline due to agricultural changes and urbanization. Of greater concern are the worsening floods, drought, and extreme temperature changes taking place in Sub-Sahara Africa that are likely to pose a more serious threat to the future well-being of this species.

Sub-Saharan Africa – Kenya

Northern Wheatears start to breed when they are one year old, and the female is responsible for building the nest and incubating the eggs. The nest is usually located in a cavity such as a rabbit burrow or a crevice among rocks, and the clutch size is typically three to eight pale blue eggs, sometimes with red-brown flecks. Often the male chooses to perch nearby and sing. The chicks are fed by both parents but become independent after about a month. They are left to find their own way to Africa as the fall migration gets underway.

Northern Wheatear Nest

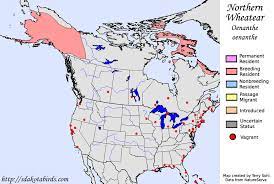

My childhood memories prompted me to write this article to acknowledge that I have failed to observe even a single Northern Wheatear during the past three decades while living here in California. It is not that they never appear, but that they are so very rare. Most cross the Pacific or Atlantic to the Old World for winter, and only the occasional straggler appears in the United States, other than Alaska, including accidental vagrants along the western coastline of California. These exceptions attract a great deal of attention and hordes of birdwatchers descend on the site if it is published. Only a dozen or so sightings have been recorded all-time in California, and mainly take place during the August to November migration period. It is only now that I realize how fortunate I was to encounter this bossy little bird during my teenage years.

Northern Wheatear North America Range Map