Sandhill Cranes are back in California for Thanksgiving

Sandhill Cranes

During early October this year, I visited the Cosumnes River Preserve, south of Sacramento, to glimpse flocks of Sandhill Cranes flying high in the sky, having just arrived to winter in their thousands among the fields, marshes, and wetlands of the Central Valley of California. They are an amazing sight. Often you hear their loud trilled calls long before you spot them wheeling above you, searching for suitable feeding and resting grounds. They are known for their incredible eyesight. As predominantly plant-eating herbivores, they choose territory that provides them with abundant food, a temperate climate, and an acceptable living environment. Sandhill Cranes roost at night in shallow wetlands and feed during the day on grain fields. They are social birds that often forage in large flocks.

The Cosumnes River Preserve was established amidst farmland in 1987, and its flood plain has become a haven for tens of thousands of migratory waterfowl, songbirds, and raptors, as well as numerous Sandhill Cranes. There are of course other locations in California to catch sight of these birds, including Woodbridge Ecological Reserve near Lodi, Staten Island near Stockton, Pixley National Wildlife Reserve near Bakersfield, Yolo Bypass Wildlife Area near Davis, Soda Lake in San Luis Obispo County, and the Merced National Wildlife Refuge.

Cosumnes River Preserve in the Evening Light of Fall 2022

Sandhill Cranes are magnificent birds, up to five feet tall (1.5 meters), and with a wingspan reaching seven feet (2 meters). Their plumage is gray, augmented with a crimson red forehead, white cheeks, and a long, dark, pointed bill. They are among the oldest species on our planet and are famous for their distinct calls and complex “courtship” dances. The latter include circling each other, pumping their heads, stretching their wings, and leaping in the air. They are one of two crane species native to North America, the other being the very rare Whooping Crane.

Two subspecies dominate California, the Lesser Sandhill Crane and the Greater Sandhill Crane. Elsewhere in North America, there are three local subspecies that do not migrate, known as the Florida, Mississippi, and Cuban Sandhill Cranes, and there is one subspecies called the Canadian Sandhill Crane that is difficult to distinguish from its related Greater Sandhill Crane. Subspecies are classifications of birds that can breed with other related subspecies, but typically do not do so. The two California cranes are identical in body shape, plumage, and color, but the Greater Sandhill Crane is up to five feet tall (1.5 meters) and the Lesser Sandhill Crane only four feet (1.2 meters). The smaller variety is the most common in California.

Lesser and Greater Sandhill Cranes

Publication of this article during the Thanksgiving month of November is appropriate because of the origins of the word “cranberry”. Cranberries are a feature of the United States Thanksgiving table and interestingly are named after Sandhill Cranes. Pilgrims and early settlers in the United States thought the cranberry fruit blossom, with its pink-white petals that curve back over the vine runner, resembled the long, slender neck, white head, and red forehead of a Sandhill Crane, and therefore called them crane-berries. Over the years the name has been shortened to cranberries.

“Sandhill” refers to the Nebraska Sandhills near the Platte River, a broad, shallow, meandering stream with many islands, where more than half a million cranes stop to rest during the spring migration.

Cranberry Flowers

Head of a Sandhill Crane

I have visited the Consumnes River Preserve several times in the past to assist groups of third graders from Sacramento’s Leonardo da Vinci K thru 8 School who participate in an annual “wild birds” outing. This visit, however, was motivated by an experience near my home in Marin County when, at about 9.00 am on September 26th 2022, I observed a pair of large birds flying eastward over the Bon Air Shopping Center near the Corte Madera Creek, seemingly preparing to fly across the San Pablo Bay. They made no noise and were flying below the remnants of an early morning fog that had allowed intermittent blue sky to push through its cover. I could see their long, straight, slender necks fully extended in front of them, they were flapping broad serrated wings in slow, regular wingbeats, their legs trailed beyond the end of their tail, and they appeared uniformly gray. Without binoculars, they were too far away for me to see their red crown but they had the profile of Sandhill Cranes. I doubt they were geese, including the Greater White-fronted Geese and Snow Geese that arrive in California around this time, because of the long legs that trailed behind them. Definitely they were not pelicans, blue herons, shorebirds, or swans, and they were too light-colored to be White-faced Ibises that occasionally visit California.

Sandhill Cranes in flight

White-faced Ibis

Greater White-fronted Geese

Snow Geese

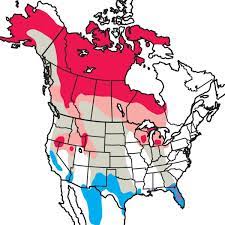

Many Sandhill Cranes use the Pacific Flyway to migrate each year, which is one of four Avian Flyways that exist in North America. Lesser Sandhill Cranes typically use this route from Siberia, Alaska, and Canada, whereas the Greater Sandhill Cranes usually breed much closer to California, in states like Oregon, Nevada, Washington, and British Columbia, and around 250 pairs are estimated to currently breed in California’s high mountain meadows and high desert. Only about 5,000 to 6,000 of the Greater subspecies winter in California, whereas the total number of Sandhill Cranes in California is projected at around 250,000, with another 40,000 wintering in southern Arizona. Population estimates for all of North America are difficult to find, but it is likely that the total number is close to one and a quarter million. Sandhill Cranes that migrate along the Atlantic and Mississippi Flyways usually winter in Florida, Louisiana, Georgia, Alabama, and Southeast Tennessee, and are generally of the Greater variety. Those that follow the Central Flyway reach Mexico, New Mexico, and Texas for winter.

Sandhill Cranes Range Map: RED-Breeding Common; PINK- Breeding Uncommon; BLUE-Winter; GRAY-Migration

Sandhill Cranes have occasionally reached Europe but are only rare vagrants. During my days in England as a birder, during the 1960s, these birds were never recorded, and the first British sighting of a Sandhill Crane was on Fair Isle during April 1981, the southernmost Shetland island in Scotland, and the second sighting, 10 years later, was on the nearby Shetland Mainland. However, there is an Old World species of crane known as the Eurasian or Common Crane that is found in northern Europe and across the Palearctic into Siberia. It is a long distance migrant that winters in North Africa. Several centuries ago the Common Crane inhabited the UK, but became extinct during the 1700s. Efforts are now underway to reintroduce the species into parts of England that provide suitable habitat. Other species I successfully saw during the 1960s and 1970s are mentioned in my novel She Wore a Yellow Dress.

Eurasian or Common Crane

I still have to record my first sighting of a Whooping Crane in the United States. It is one of the rarest North American birds and almost became extinct in the 1940s because of unregulated hunting and habitat loss. An estimated 21 was all that were left by 1941. Today, there are around 1000 birds, including those reintroduced after captive breeding. The majority nest in central Canada and winter in Texas, although a few breed in Wisconsin and winter in Florida.

Whooping Cranes

The opposite is true for Sandhill Cranes. This species is currently not threatened and its population in parts of the United States has apparently increased by an annual rate of five percent since the mid-1960s, due to wetland restorations and abundant food. It remains illegal in many states to hunt Sandhill Cranes, and those states that do allow the sport (from Saskatchewan down to Texas), usually impose either a very short season or strict quota limits. The meat of Sandhill Cranes is believed by some to be the best among migratory birds, and is sometimes referred to as “The Ribeye in the Sky”.

Unfortunately, by 2080, climate change may rob this species of over 50 percent of its winter habitat, with the likelihood that a significant reduction in its population will occur. Those of you worried about the impact of global warming may wish to add this possible outcome to your arguments for change.