The Growing Abundance of Canada Geese

Canada geese breeding season is underway at my golf course, and my erratic golf shots risk the lives of these birds as they eat, mate, and nest nearby. Their population seems to increase each year. Their eggs have hatched and the baby goslings, dressed in soft, fluffy, yellow and gray down feathers, come close to my danger zone as they learn how to feed. Goslings hatch with their eyes open, leave the nest within 24 hours, but cannot fly for the first nine to ten weeks.

Canada geese are large, aggressive waterfowl, 30 to 43 inches long (75 to 110 cm), with wingspans of 50 to 75 inches (125 to 190 cm). They are recognized by their long black neck, black head, crown, and bill, and contrasting white cheeks and chinstrap, with gray-brown upperparts and paler feathers below. The various subspecies differ in size but all are recognizable as Canada geese. The Western or Moffitt’s subspecies is the one that I usually see grazing at the golf course. They are herbivorous, forage on grass, and consume aquatic vegetation and algae. During fall and winter, they catch insects and rely on berries and seeds.

Moffatt’s Canada geese

The smaller, northern nesting subspecies of Canada geese, such as Taverner’s, Dusky, and Lesser, typically migrate long distances, often in large V-shaped formations, whereas my golf course variety opt to be “year-round” residents. Canada geese breeding in northern Canada and Alaska move southwards throughout the US as cold weather arrives, whereas those that nest in the Lower 48 U.S. states generally stay local. The population of Canada geese in North America is stable to slightly increasing, but the number of year-round residents is dramatically growing. Reasons include the longer breeding season in milder climates, the absence of hunting in urban habitats, and their choice of predator-free sites.

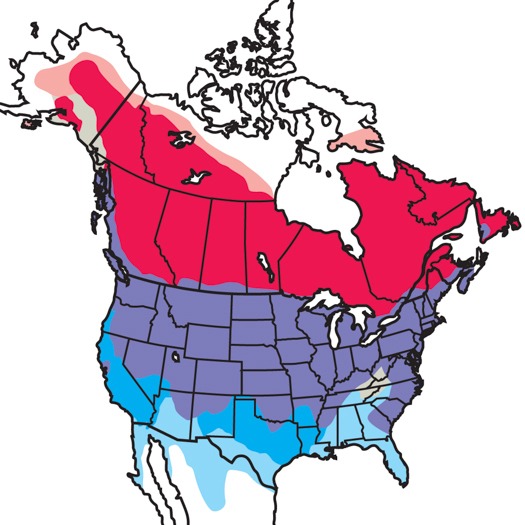

Canada geese range map, all seven subspecies: red breeding; pink limited breeding; purple year round presence; blue migrant mainly in winter

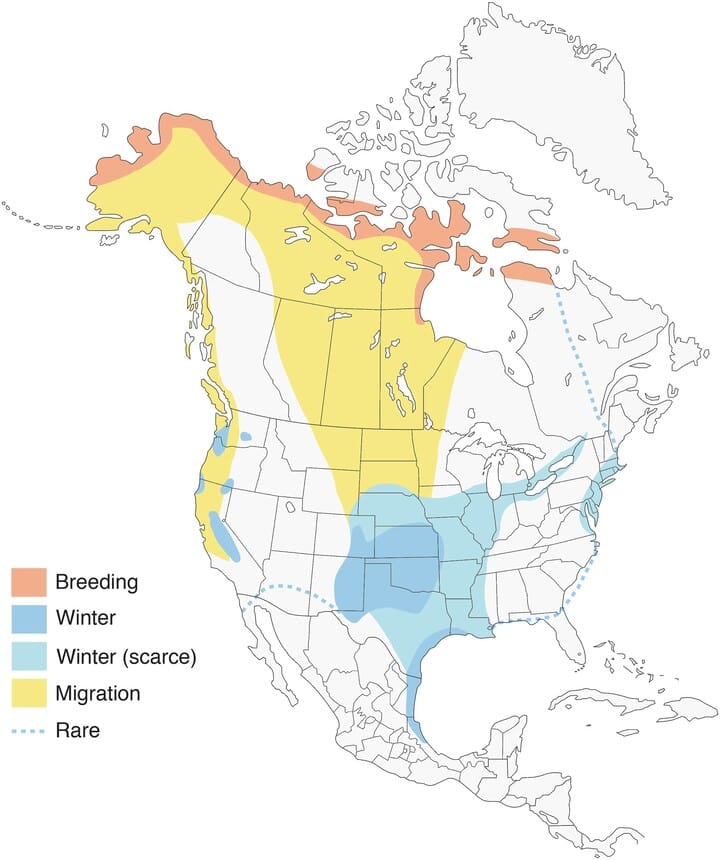

You may see a small version of the Canada goose embedded in groups of larger birds, especially during winter. Other than their size, which is about 25 inches (64 cm) in length, they are identical to their larger relations, except for a somewhat rounder and stubbier head. These are now a separate species, classified as cackling geese, and named after the high-pitched call they make. They are about the size of a mallard duck. Their bigger Canada geese cousins are nicknamed honkers.

Cackling goose on the right

The creation of this species dates back to 2004 when the American Ornithologists’ Union gave cackling geese their own separate status. The British Ornithologists’ Union followed suit in June 2005. All four subspecies of cackling geese nest on the Canadian and Alaskan tundra and migrate south for winter in search of food and to avoid the cold weather. They are identified by their small size. By the 1960s there had been a drastic population decline in this species due to recently introduced predators. By the late 1970s, their population had declined to about 100,000 and the bird was on the Endangered list. Subsequent conservation efforts have resulted in a present day population estimated to be over three million.

Cackling goose range map

So what is going on with Canada geese, and what is their history? How did a native North American species find its way to Europe and New Zealand? As their name implies, they originated in Canada, but most seem to live outside their ancestral home.

Biologists believe that there are now more Canada geese in North America than at any other time in history. By the late 1800s, the largest subspecies of Canada geese (the giant Canada goose), that bred in southern Canada and the northern United States had, to a great extent, disappeared. Early settlers gathered their eggs, hunted them for food, and destroyed their habitat. Consequently, in the early 1900s, geese bred in captivity were introduced into the southern part of this subspecies former range, and other areas where they had not bred before. The outcome has been an astonishing explosion in the numbers of Canada geese. In 1950, there were perhaps one million Canada geese in North America, whereas today the number has billowed to around seven million, of which approximately half are resident.

They have thrived as a result of new feeding opportunities and the protection of living in parks, suburban wetlands, on reservoirs, and using lakeside lawns and golf courses. They tolerate humans, and it is believed that the larger subspecies have stopped migrating because of the improved availability of food and suitable year-round climate. Unfortunately, this growing population is causing environmental damage because of the birds’ droppings, overgrazing, sometimes aggressive territorial behavior, the noise they make, and the risk of causing aircraft collisions. They have a life span of 10 to 24 years, raise one brood annually, and have a clutch of two to eight eggs. Ongoing discussions at national and local levels are taking place to decide what should be done to control their numbers, especially the “resident” variety.

Clipped corn seedlings

In Europe, very few Canada geese managed to make it there naturally. Most of today’s population originates from ancestors that were introduced. As early as the late 1600s, Charles II of England added Canada geese to his waterfowl collection in St. James’s Park, but Canada geese remained relatively uncommon in the UK until the mid-1900s when there was an estimated 2,200 to 4,000 birds. Today the number has surged to around 125,000.

St. James Park, London

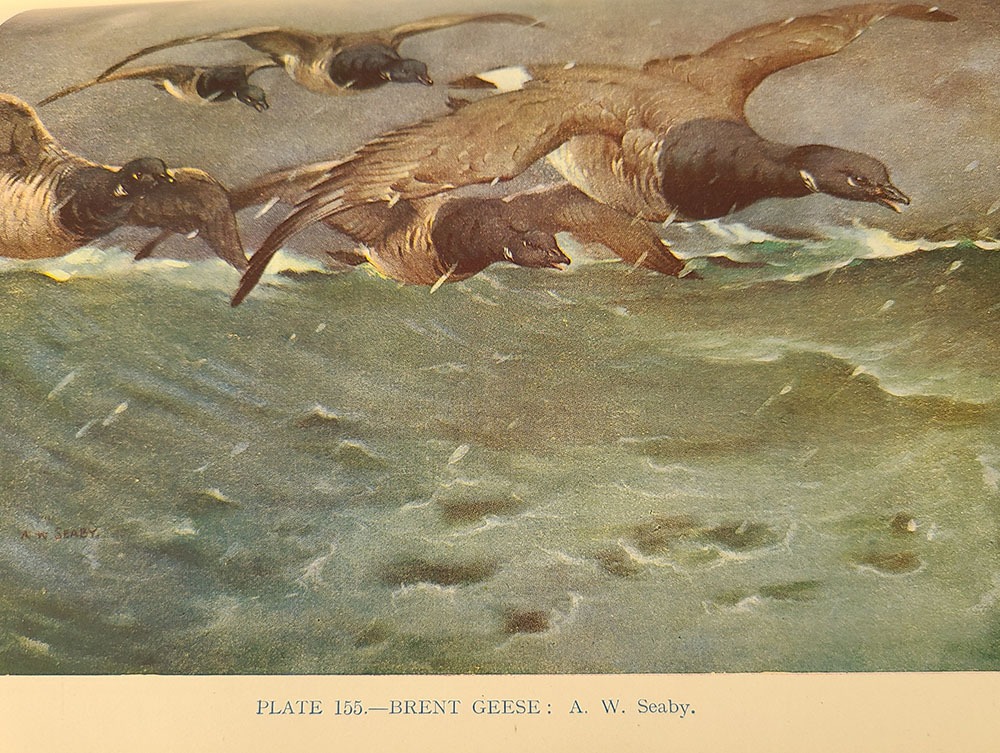

When I look back on my 1950s early birdwatching days in the UK, I see that my first bird book, received on my tenth birthday (British Birds by Kirkman and Jourdain), makes no reference to Canada geese. Six geese species are mentioned, with one – the brant or brent goose – looking similar to a Canada goose. However, it lacks the white cheek of Canada/cackling geese. It is small (22 to 24 inches/ 55 to 60 cm in length), has a black head and neck, a white spot in the side of its neck, a grey-brown back, and either a pale or dark belly. Brent geese breed as far away as Alaska and along the central Canadian Arctic, across northeastern Greenland, to northern Europe, and onwards east into Siberia. These geese migrate south during winter in North America, to the northeastern United States and along its Pacific Coast, and in Europe to the coastlines of north-west European countries. About 100,000 migrate to the UK. Those with dark bellies appear in eastern England and travel from Russia and Siberia, and the pale bellied ones in the north east of Britain migrate from Spitsbergen and Greenland.

Extract of illustration from British Birds by Kirkman and Jourdain

Brent goose range map

So what has caused this dramatic increase of Canada geese since the end of World War 2 in the UK? The bird is now regarded as a pest by farmers and a nuisance by many members of the general public.

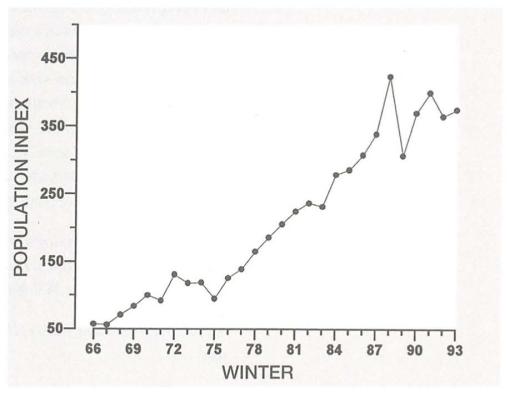

Canada geese nest

In 1939, the hunting of wildfowl in the UK, including Canada geese, was reduced to only part of the year by the Duck and Goose Act, followed in 1954 by the Protection of Birds Act that made it illegal to collect any wild birds’ eggs and to destroy their nests. As a result, the number of Canada geese increased in their traditional locations, and new methods of control became necessary. Since these birds were relatively easy to catch, they were trapped and transferred to suitable new locations where geese were absent. However, because those remaining in the original site quickly replaced their lost numbers, and the transferred geese successfully bred, their population rapidly grew. By 1968, Britain’s Canada geese had more than doubled from the early 1950s to about 10,000, then rose close to 20,000 by 1978, and in 1999 reached 82,000.

Historic trends in the UK for Canada geese

And then there is New Zealand where Canada geese were introduced to the South Island during 1905 and 1920 for hunting purposes, and in the 1970s, they were added to the North Island. Their population has grown spectacularly, with current estimates of about 60,000 birds, of which two-thirds are located on the South Island. Canada geese are now regarded as a serious pest because of their alleged pollution of waterways, damage to pastures and crops, congregations in public places, and the safety risk to aircraft. However, modern day efforts to control their numbers have so far failed. In 2011 Canada geese were removed from New Zealand’s list of gamebirds, and responsibility to control their numbers transferred to farmers. The idea was that the species could now be hunted year round, hunting would not require a license, and there would be no limit on the numbers that hunters could shoot. Unfortunately, farmers seem to lack the resources to fulfill these responsibilities.

Canada geese in New Zealand

So what is to be done to prevent this relentless growth in the Canada geese population? The solution likely lies in addressing the cause of the problem rather than its symptoms. In New Zealand, effective national coordination of wildlife probably needs to be reinstated. In North America and the UK new management controls should be introduced, and the public educated on the need to limit Canada geese numbers.

Methods include reducing the availability of nesting sites and sterilizing eggs, restricting the birds’ sources of food, and lessening their sense of well-being. The latter includes closing access to bodies of water from the land, installing streamers or reflective ribbon to discourage the birds from spreading, carrying out hazing and harassment to scare them away, and maybe using chemical lawn treatment to make the grass unpalatable.

Meantime, I shall continue to complete my 18 holes on the golf course, and hope that I can continue not to injure any Canada geese! While the geese with goslings appear smart enough to stay away from the links, many of those not breeding risk their lives by foraging on the fairways and wandering across the greens.