The Endangered Western Snowy Plover

I have volunteered to assist with the protection of the Western snowy plover during their California coastal breeding season this year from March to September. The following is published to coincide with my training as a docent.

This small shorebird is approximately the size of a sparrow, weighs less than two ounces (55 grams), and is about six inches (15 cm) in length. It makes its home on flat, unraked sandy beaches, dry mud or salt flats along the Pacific Coast and estuaries, from Washington State through Oregon, and onto California and into southern Baja California, Mexico. Formerly, the Western snowy plover nested on a large part of this shoreline but today these birds are rarely seen. Prior to the 1970s, it is reported that at least 53 California locations were homes to these plovers, but a few years later that number had halved. Today the Pacific coast population is estimated to be around 2,500, with most of California’s coastal breeding birds found south of San Francisco. The bird’s conservation status was raised to Endangered in March 1993, and probably less than 1000 breeding plovers occupied the West Coast by the year 2000. This number is now increasing. There are also snowy plovers that breed in interior California, south-central Oregon, Nevada, and several other western states, and some of these winter along the West Coast.

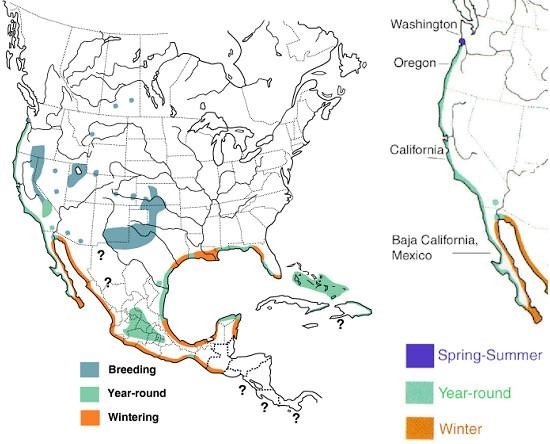

Distribution of snowy plovers

The right-hand side of the above range map illustrates the distribution of the Western snowy plover on the West Coast. It is this subspecies that has received most conservation attention. Snowy plovers east of the Sierra Nevada mountains and the Rockies appear less threatened, and populate the Great Basin, parts of Texas, the Central Plains, much of the Gulf coast, the Bahaman islands, and in Central Mexico. Most of these birds are thought to belong to separate subspecies from the Western snowy plover. Also, as well as being called snowy plovers, in some places they are known as Cuban snowy plovers or beach plovers. Genetic studies suggest that the nearby Great Basin population is no different than the Western snowy plover but that there may be demographic and adaptive variations. Those living further east appear to be a different subspecies. Birds of the same name also occupy the west coast of South America, from southwestern Ecuador through western Chile, and are thought to belong to their own subspecies. It is estimated that about 31,000 breeding pairs of snowy plovers exist worldwide.

Cuban snowy plover

The coastal Western subspecies roosts in small depressions on the sand or on the leeward side of objects such as driftwood, kelp or dune vegetation. Their pale plumage blends readily with dry sand or salt flats, making them very difficult to see when they are crouched. They gather in loose colonies or in isolation, and sometimes can be seen scurrying across their sandy habitat like inconspicuous puffs of sea foam. They prefer wide open beaches, and forage on insects, especially beach flies, marine worms, and small crustaceans. Typically they hunt for their food high up on the beach.

Their eggs (usually three camouflaged white and brown speckled) are laid in nearly invisible nests on the ground and are vulnerable to being taken by predators or being trampled on during their approximate 28 days of incubation. The peak hatching period is from early April through mid-August, with most birds site-faithful, returning to the same breeding area each year. The male incubates the eggs during the night and the female does the same for most of the day. Two or three broods may be produced annually whereas the eastern snowy plovers usually raise only one.

The main threats to the Western snowy plover are habitat loss, the spread of European dune grass, human-caused disturbance, and the impact of predators such as dogs, raccoons, coyotes, foxes, crows, ravens, and falcons. About a third of the bird’s population stays in its coastal breeding grounds during winter whereas the remainder migrate a short-distances, north or south, typically for distances of no more than 300 to 500 miles.

Above, Western snowy plover chicks: the chicks leave their nest about three hours after hatching and accompany their parents to find suitable sources of food. Almost immediately they can forage independently and fly after about four weeks.

In appearance, the adult Western snowy plover is pale gray-brown above and white below, with a white hind neck collar and dark lateral breast patches, forehead bar, and eye patches. Early in the breeding season, a rufous crown is evident on breeding males, but not on females. In nonbreeding plumage, the sexes cannot be distinguished. The short bill and legs are blackish. During courtship, the male defends its territory, usually makes several scrapes, and the female then chooses which scrape she prefers by laying eggs in it. Adult plovers will attempt to lure people and predators away from hatching eggs with alarm calls and distraction displays. Their call is a short, sharp, whistled tu-wheet.

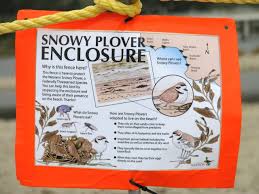

Various methods, including beach closures, are used to protect the birds’ coastal breeding grounds. Enclosures and sometimes symbolic fences are erected to protect the nesting area and to prevent predators interfering with breeding. Educational signs and brochures explain what is taking place, announcements are posted on why dogs should be kept on leash, written notices request that kelp and driftwood be left on the beach and that littering should be avoided. There is a ban on flying kites and similar objects, and lighting fires is prohibited. Sometimes docents are stationed nearby – especially at weekends – to explain the situation and to answer visitor questions. Efforts also may be made to restore habitat and expand the breeding area.

The presence of snowy plovers in Europe has never been confirmed and consequently these birds are considered a New World species. However, until 2009, it was thought that the Eurasian Kentish plover, named after the county of Kent south-east of London, was the equivalent to the North American snowy plover. Genetic studies, however, have shown that this is not true, and in July 2011, the International Ornithological Congress (IOC) announced the separation of the two groups.

Kentish plover distribution map: light green breeding; dark green resident; blue non-breeding

Growing up in England during the 1950s and 1960s, the Kentish plover had only recently ceased breeding in Kent, where it had occupied vast expanses of shingle near Dungeness. British breeding numbers were estimated to have shrunk to about 40 pairs by the mid-20th century, and were mainly located in Kent, but with a few birds in the counties of Sussex, Suffolk, and Lincolnshire. Apparently, the last UK pair to breed was in Lincolnshire during 1979. Today the Kentish plover is just a rare passage visitor to southern England with, for example, only 13 recorded sightings during 2016. Its disappearance is attributed to loss of habitat and the greater recreational use of beaches, and early during the last century, its eggs were taken and individual birds killed for decorative purposes. Nonetheless, this neat and charismatic wader remains widespread in other parts of Europe, and migrates to the northern half of Africa, northern India, and south-east Asia, for winter.

Dungeness, Kent, England

Unfortunately, I did not have the resources to travel to Kent during my childhood to try to spot the Kentish plover, and had to satisfy myself with observing its relatives such as lapwings near my home, and ringed plovers, golden plovers, and grey plovers during my visits to Yorkshire’s Spurn Point Bird Observatory. All four varieties still nest in Britain.

Let us hope that the current steps being taken to protect the Western snowy plover along the West Coast of North America will be successful, and that the species does not suffer the same fate as the Kentish plover in England. We should be grateful to all the people who help with this conservation effort.