Flickers, Sapsuckers, Wrynecks, Members of the Woodpecker Family That Ignore Their Family Designation in Their Title

Woodpecker that does not drill holes, Northern Flicker males (red-shafted /yellow-shafted)

Photo Credit – Cornell Lab. of Ornithology

The Northern Flicker (a species in the Woodpecker family) is on my golf course for the winter. Several birds recently flew low alongside the eighth tee, exhibiting their characteristic undulating flight broken by regular glides and their loud, rasping cries. Some quiet ones dug dirt near the sixth hole to catch ants. Their smaller relative, the Red-breasted Sapsucker, is leaving its signature by drilling rows of small holes less than half an inch apart as horizontal lines on selected tree trunks across the course. It uses these holes as wells to feed on the accumulated sap. Since neither species exists in Europe, I have included their European Wryneck cousin to represent the Old World.

European Green Woodpecker

Photo Credit – iNaturalist

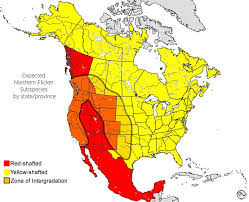

All three species belong to the Woodpecker family. The Northern Flicker is a winter visitor and a resident, and in California, the species is represented by the “Red-shafted” variety. The “Yellow-shafted” subspecies is distributed east of the Rockies, although the two interbreed. Hybrid birds often have a mix of plumage characteristics from both sides. Fifty percent of their diet is ants, with the remainder of beetles, moths, grub larvae, and fruits and nuts in winter. They have extra-long tongues, up to two inches beyond the tip of their bills, coated with sticky saliva.

While Flickers are absent in Europe, their eating habits are like those of the European Green Woodpecker, and juveniles of this species can look very similar to Flickers.

Northern Flickers are beautiful birds of medium size, with black barring on a light grey back, a spotted belly and chest, a white rump, and red feathers on the tail, underwings and some wing feathers. For the “Yellow-shafted” variety, the under feathers are yellow, not red. Males of both subspecies have a moustache of either red or black feathers.

Like most woodpeckers, Northern Flickers generally nest in holes in trees, although sometimes they occupy earthen burrows left by other birds. They will also drum on trees to defend their territory and communicate with each other. The maximum life span is a little short of 10 years, and their preferred habitat is woodland, the edge of forests, city parks, and areas with scattered trees. The estimated global breeding population is around 10 million birds. Numbers have declined because of human activity, but the species remains off the endangered list.

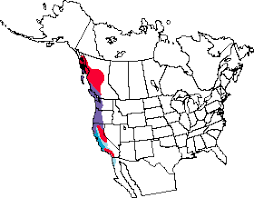

But now let me present the Red-breasted Sapsucker, the most common Sapsucker in California. There are also the Red-naped Sapsucker (Rocky Mountains and Great Basin), Williamson’s Sapsucker (northern Mexico to British Columbia, including eastern California), and the Yellow-bellied Sapsucker (Canada and northeastern United States). Until 1985 the Red-breasted, Red-naped, and Yellow-billed Sapsuckers were considered the same species.

Woodpecker with a sweet tooth, the Red-breasted Sapsucker

Photo Credit – All About Birds, Cornell Lab of Ornithology

Red-breasted Sapsucker Range

Photo Credit – BirdWeb

Red: summer; Purple: resident; Blue: winter.

The Red-breasted Sapsucker, about the size of an American Robin, is primarily a winter visitor to my part of northern California. I am more likely to see its presence by spotting its tidy lines of pecked holes in the trunks of trees than seeing the bird. The plumage is similar in color to other woodpeckers but with a more extensive covering of bright crimson on the head and upper breast. Unfortunately, they attack living trees and can kill them by girding their trunks with closely spaced holes. They nest in holes in the trees excavated by the males. The lifespan is around five years, and estimates suggest a global population of around 2.8 million. The species is of low conservation concern, and, in the past, they were shot as orchard pests; now, they are protected.

Woodpecker that mimics a snake, Eurasian Wryneck

Photo Credit – The Wildlife Trust

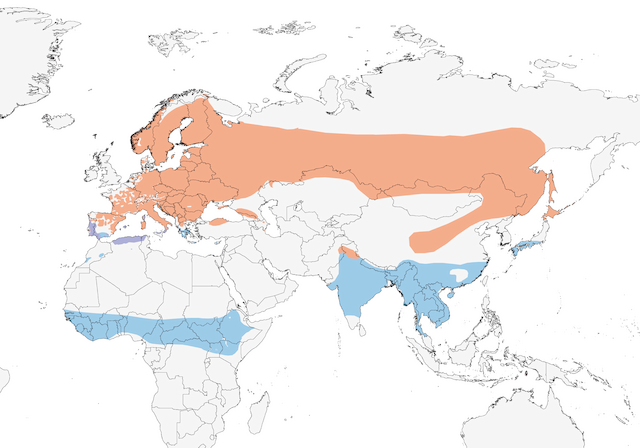

Eurasian Wryneck Range

Photo Credit – Cornell Lab, Birds of the World

Orange: summer; Blue: winter; Purple: resident

I never recorded an Old World Eurasian Wryneck while growing up in England. They were widespread and nested in central and southern England, but I stayed in Yorkshire then. Their last confirmed breeding was in 2002; the species is now a rare passage bird in spring and August/September, appearing along the British east and southern coasts. They are small birds, sparrow-sized, and because of their greyish plumage mottled in pale brown, they are inconspicuous. They have a broad black stripe down the middle of their crown and back. Shape-wise, the birds are slim and elongated with a long tail. Like Flickers and the Green Woodpecker, they prefer a diet of ants, moths, and insects gathered in the soil and on decaying wood. Their bills are small and weak; they have long, sticky tongues and do not hammer or excavate, so for nesting, the birds use woodpecker holes or occupy wall crevices.

The species name comes from their ability to twist their necks nearly 180 degrees. “Wry” originates from the Old English verb meaning “to contort, twist, or turn.” They do this and sometimes hiss snake-like to frighten off predators (hence their nickname, snake bird). Preferred habitat during summer is open country with scattered trees, orchards, parklands, gardens and fields. As shown on the Range Map, they are long-distance migrants, breeding in Europe and Central Asia, and with the European birds wintering in central Africa. Despite rarity in Britain, their global population is estimated to be three to seven million birds, with 50 percent breeding in Europe.

Population numbers are believed to be declining because of climate change, such as increased rainfall during the breeding season, loss of nesting habitat, and the use of pesticides. However, none of the three species I presented are seriously threatened.

A Wryneck

Photo Credit – eBird (when held, the bird may contort its neck and feign death)