Waterhen, Moorhen or Gallinule – Which is It?

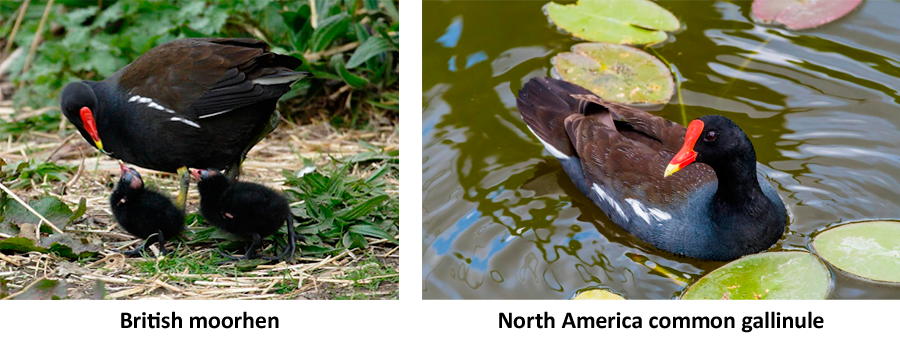

Growing up in Yorkshire, I called them waterhens (now more usually known as moorhens). They are humble birds, preferring freshwater wetlands, and are sedentary, except that they are joined by birds moving from north-west Europe to winter in the UK. As their name implies, they are the size and shape of a chicken, they “cluck” like a hen, and lay a similar number of eggs. As a child, I sat on the edge of ponds and talked to the birds as they sat incubating their eggs on bulky platforms of reed stems. Usually there were 6 to 10 eggs in the nest, one laid each day, but occasionally the number was as high as 15 to 20, a sign that cooperative breeding was taking place. My novel Unplanned gives you a sense of why I connected so closely with these birds.

Common moorhen nest and eggs

Common moorhen nest and eggs

When they were disturbed, the sitting bird would quietly slip off the nest and disappear into the bulrushes. The dark brown plumage on their back and wings, and the bluish-black feathers on their belly made it difficult to see them among the vegetation or afloat on the dark-colored water. I would try to spot their chunky bright red bill with its citrus-yellow tip, or look for the white stripes on the flank. As soon as I left, I knew the waterhen would return to its nest. They are mainly sedentary birds, rarely leaving their territory, although you could see them poking around on land during winter when the ponds froze over.

Some of my ornithological experts called them moorhens even though the last place you would find them would be on the moors. It turns out that the word “moor” is derived from the old English word “mere”, which in turn gives rise to the word “marsh”. This made sense since I occasionally visited Hornsea Mere, a large expanse of freshwater near the south-east coast of Yorkshire, where I would see many moorhens.

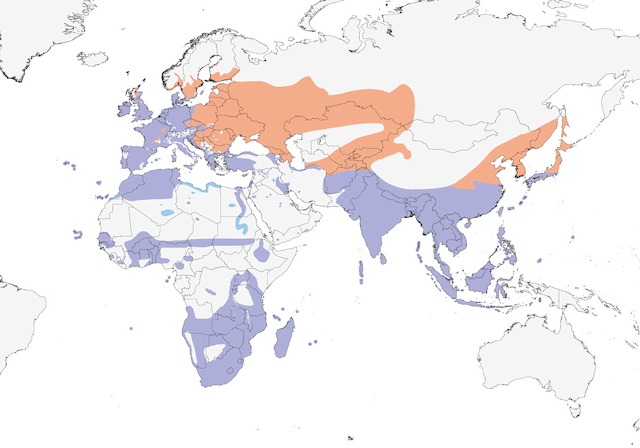

Common moorhen Range Map

Common moorhen Range Map

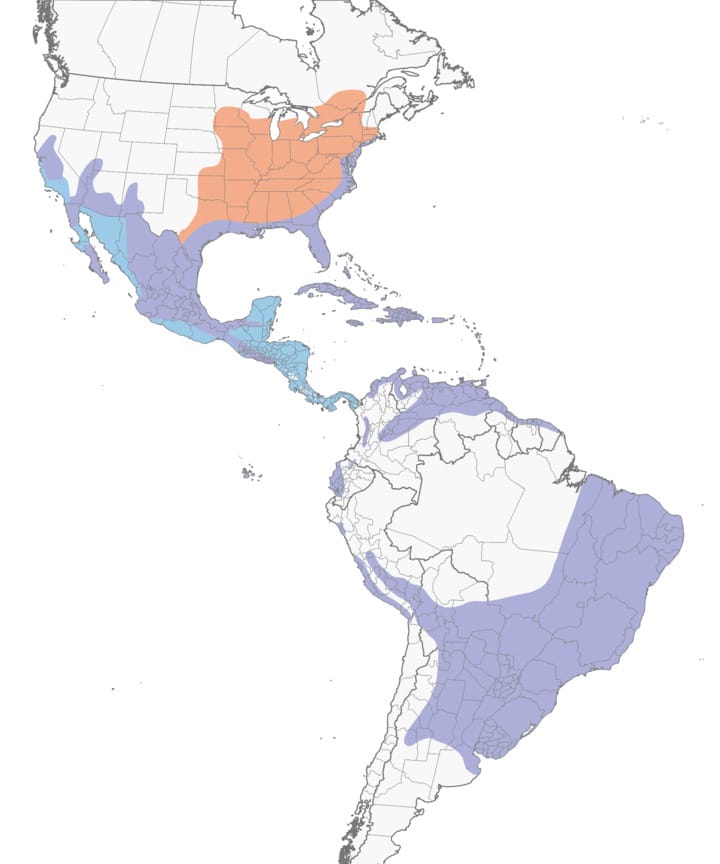

When I moved to the California in 1979 I thought I was still seeing moorhens, but was told that they were common gallinules, apparently the Latin word for “small hen”. To me they looked the same. They walked on floating vegetation and behaved secretively, just like the ones I knew back home. However, after much debate, they were declared a separate subspecies. Apparently they “cluck” differently from moorhens, and there are slight morphological differences affecting their red truncated frontal shield. The species inhabits the southern US, central America, and a large part of South America, and is just one of the birds I discovered in California where they use a different name from the one used in Europe.

Apparently, this North America bird also has a relative on the Hawaiian Islands of O’ahu and Kaua’i, known as the ‘Alae ’Ula (burnt forehead). Legend has it that the bird brought the fire from the volcano to the gods of the Hawaiian people, but during the flight the bird’s white forehead was scorched red by the volcano’s fire.

Common gallinule Range Map

Common gallinule Range Map

I later discovered this “same-bird, different-name” phenomenon applies to other species in North America. For example:

- guillemots vs. common murres: the British guillemot takes its name from the French word for William – Guillaume – whereas the North American common murre is named after the call that it makes – a purring and murmuring.

- divers vs. loons: the British divers (i.e. great northern, black-throated and red-throated) are believed named after their ability to catch fish, whereas the North American name probably originates from the old English word “lumne”, which means awkward or clumsy, and describes the bird’s poor ability to walk on land. Alternatively, it may have been taken from the Norwegian word “lune”, meaning to lament, and which describes the bird’s plaintive call.

- skuas vs. jaegers: the smaller British skuas (i.e. Arctic, Pomarine and long-tailed) have the same name as their larger, dumpier, more ferocious cousin, the great skua. While the latter keeps its name in North America, the others are called jaegers. The word skua originates from the Faroese name for the bird -skuguur – and since all skuas harass other birds into dropping or disgorging their food – it appears that all species of this bird in Britain are named skua. In North America, the name jaeger is an extract from the German and Dutch words for hunter , reflecting its habit of chasing other sea birds.

- tits vs. chickadees: Britain has seven species of tit (blue, coal, great, long-tailed, marsh, willow and crested), with the name derived from the old English word meaning “something small”. The name was in use back in the 1540s, and if you are wondering about the word being the slang term for a woman’s breast, this latter designation was inaugurated only as recently as 1928. The colorful plumage, habitat and shape of these birds distinguish them from one another. Their closely-related North American cousins are called chickadees because of their alarm call, but similarities of appearance exist:

- coal tit vs. chestnut-backed chickadee

- willow tit vs. black-capped chickadee

Other species of chickadee are unique to North America, except for the gray-headed chickadee which is called the Siberian tit throughout its domicile in northern Eurasia.

But back to moorhens and gallinules. There is another relative in the United States known as the purple gallinule that inhabits freshwater swamps and marshes in the southeastern states of the US. They have brilliant purple, blue, and green feathers, and while I have not seen one in California, they have a reputation for vagrancy, with individuals traveling as far west as here, and all the way down to the Galapagos Islands.

Whether they are called moorhens or gallinules, all these birds remain common and widespread, and generally are not at risk from climate change and other interventions, although loss of habitat is a general threat. In the UK, however, the moorhen is on the Amber conservation list because of its population decline during the 1970s and 1980s, and the current reduced clutch sizes during breeding, which possibly indicates a higher level of predator interference.

Purple gallinule

Purple gallinule