Buffleheads: Ducks that Nest in Trees

It is the start of winter here in Northern California, and a time when tiny Buffleheads, the smallest ducks in North America, arrive to spend their non-breeding season in the state. They are one of 29 duck species in North America and tend to return punctually each year to the same location. Whether I am walking the dog or doing some serious birdwatching, these black-and-white ducks appear in small groups or in pairs, and sometimes individually, on sheltered estuarine waters along the Pacific coast, such as the lower reaches of the Corte Madera Creek.

When disturbed, they take flight, sometimes by running a short distance on the surface of the water, but unlike other diving ducks, they can also lift off directly, when they choose. They fly fast and low over the water with rapid wingbeats, and are silent in flight, making no whistling or quacking noise. They can travel at up to 48 miles (77 km) per hour during migration. While on the water, they dive for their diet of mainly aquatic insects, crustaceans, and mollusks, and you can see them leap slightly forward and then plunge below the surface of the water. They usually remain underwater for up to 20 seconds, but sometimes stay submerged for over a minute, popping up far away from where they disappeared. I have yet to see one on dry land.

Buffleheads in Flight

Buffleheads are bestowed with a large, high-crowned head which is the reason for their name, first being called “bull-headed” using an ancient Greek word, and then this description became “Buffalo Head”, and eventually was shortened to “Bufflehead”. Buffleheads also attract the nickname of “butterball”, a reference to the large amount of fat they carry during migration, and in some places they are known as ”the chickadee of the duck world” because of their small size. The species is native to North America where its current population is around 1.3 million, and this number is believed to be increasing.

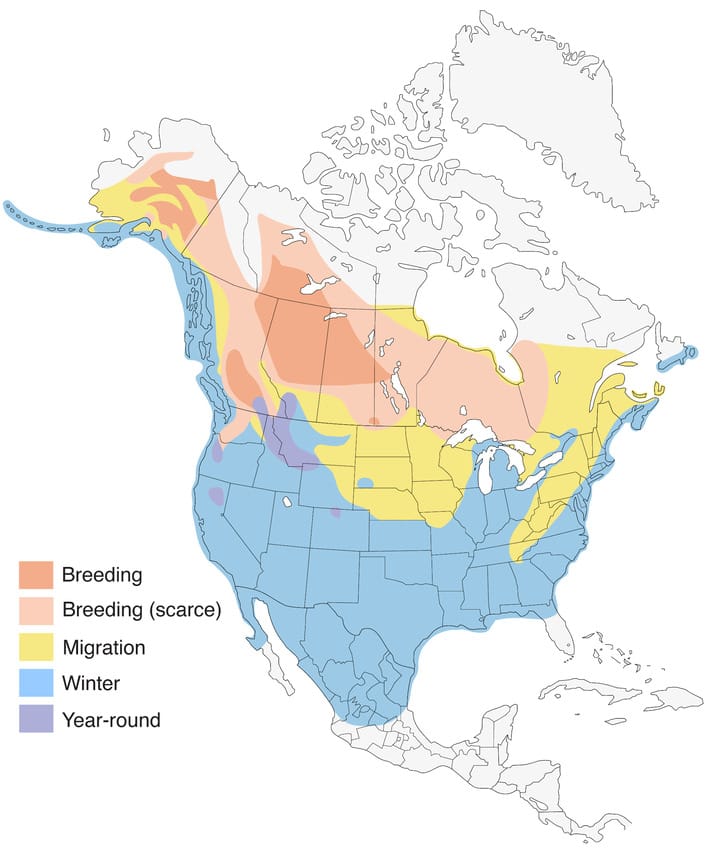

Bufflehead Range Map in North America

Buffleheads are rarely seen outside of North America, although individual birds occasionally show up in adjacent countries such as Japan, Greenland, and Iceland, and in parts of Europe, where they are considered a very rare migrant. The Bufflehead is mentioned in the Bird Book I used in England during my 1960s birdwatching, but says that the presence of these birds in Britain is “Accidental”. Indeed, as recently as 2016, only a cumulative total of 17 individual Buffleheads had been recorded in the UK since the species initially appeared during 1920. Most sightings are recorded in the Midlands of England, rather than close to the west coast, and that has led to speculation that some of these birds may be escaped ornamental ducks. As far as I know, none have been recorded at Spurn Point on the east coast of Yorkshire, my favorite bird watching haunt during the 1960s, and just one elsewhere in the county. The opportunities for birdwatching during the 1960s at Spurn Point are described in my memoir-style novel titled She Wore a Yellow Dress.

Buffleheads are only 14 inches (35 cm) long, compared with the Mallard’s 23 inches (58 cm). The adult male is the most colorful, with a large white patch behind its eye and around the back of its head. Otherwise, the rest of the head and back are black with a green and purple sheen. The underbelly is entirely white, making it highly distinctive on the water. In contrast, females are generally gray below and brown above, with a characteristic white patch on the side of their head.

Buffleheads are monogamous and can mate for life. However, since their average life span is only around 2.5 years, having a partner for life may not be too difficult. Their migration north for breeding purposes starts during February when they fly under the cover of darkness to avoid predators. Ninety percent of the breeding population is believed to be dispersed westward from Manitoba in Canada, with a few non-breeding birds staying behind for summer, as far south as California. The return trip begins once their summer habitat begins to freeze over. Those nesting in eastern Alberta typically migrate to the eastern United States and the Gulf Coast of Mexico, and birds from western Canada migrate south along the Pacific Flyway.

There is always a risk of confusing the identification of Buffleheads with other species of diving duck. For example, a male Bufflehead may be confused with a Hooded Merganser as both birds possess similar large white patches on the back of their heads and catch their food in a similar manner. However, they are not related, and while the male Bufflehead is white on its lower half, the Merganser is brown. Also, the Merganser has a thin bill to catch fish whereas the Bufflehead’s bill is more duck-like.

Pair of Hooded Mergansers

Ducks that dabble for food on the surface of the water by tipping their bodies upside down should not be confused with Buffleheads because of this feeding behavior. Such species include Mallards, Shovelers, Wigeon, Teal, Gadwalls, and Pintails.

Scaup ducks that dive to feed are similar in that they display white flanks but are distinguishable because they have no white patch on their head and are much larger than Buffleheads (close to the size of a Mallard).

Lesser Scaup – Male

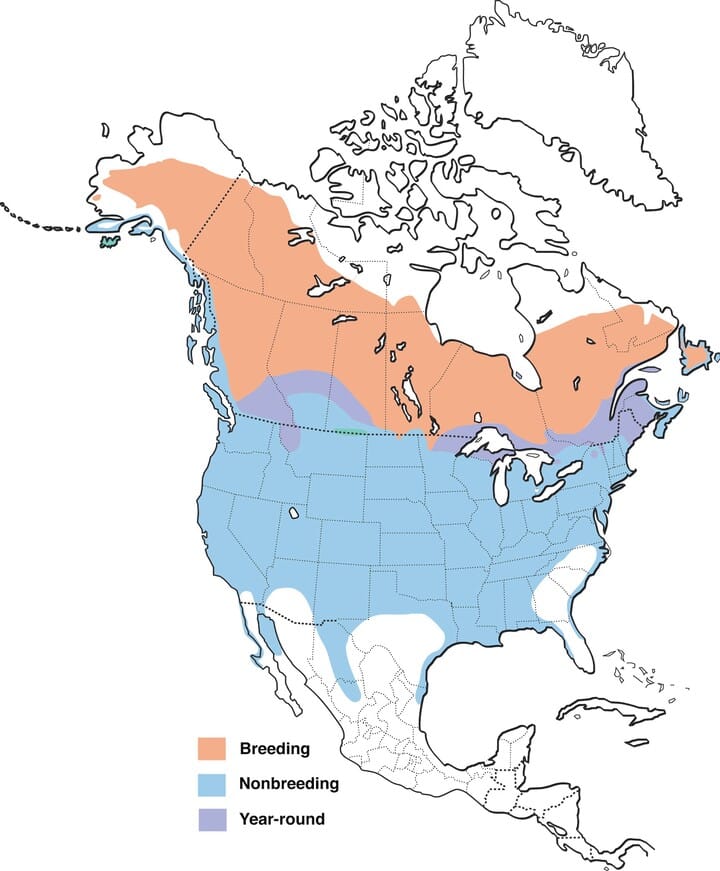

There may be confusion with two other species of diving duck, called the Common Goldeneye and the Barrow’s Goldeneye, that are named after their brilliant yellow eyes, surrounded by black in the case of males, and deep brown for females. This possible mistake in identification is due to the white underbelly of the male Goldeneye, the iridescent green on its head, and the white patch on the male’s face. The Common Goldeneye is found widely across the US and Canada, whereas the Barrow’s species is restricted to the northwest and far northeast of North America.

Common Goldeneye

Barrow’s Goldeneye

Common Goldeneye Range Map

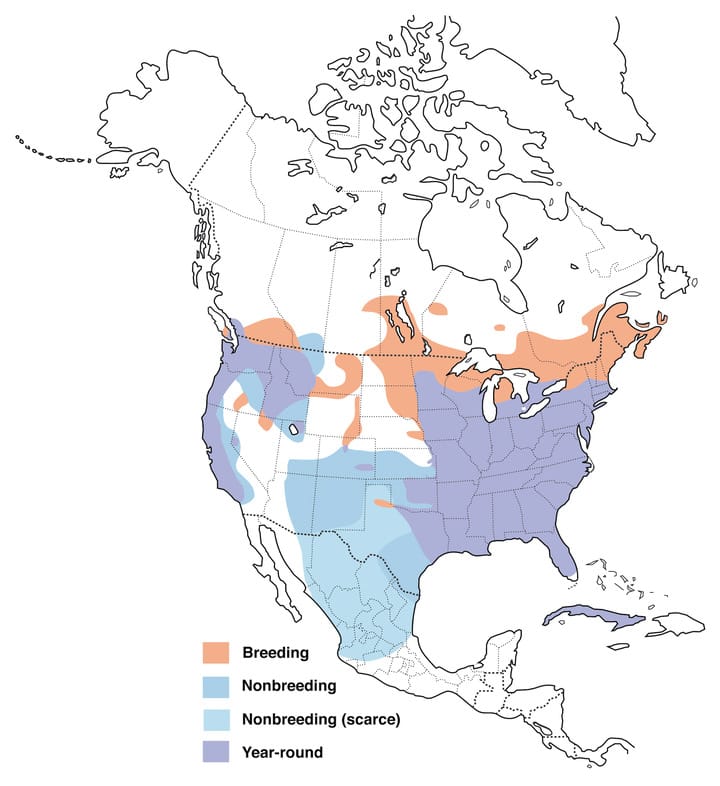

It is also these three species of duck that compete with Buffleheads for the best cavities and hollows in trees to be used as nesting sites, despite the physical limitations of webbed feet and the preference of ducks to feed on ponds, lakes, rivers, and along seacoasts. Another possible competitor for tree cavities is the Wood Duck but its breeding territory is largely in the United States, and therefore south of the territory in which Buffleheads nest.

Wood Ducks – Male and Female

Wood Duck Range Map

The Bufflehead appears to prefer cavities in aspen and poplar trees, although it will use holes in Douglas firs, ponderosa pines, and black cottonwoods. Holes excavated by Northern Flickers appear as the duck’s first choice since these cavities are small and deep enough to provide security and prevent the larger Goldeneye duck from taking over, to the extent that they will kill the Bufflehead occupant if they have to. Females select the nesting cavity that is usually located two (60 cm) to ten feet (300 cm) above the ground so that the ducklings can safely leap and fall to the ground a couple of days after hatching. An average of nine cream to buff-colored eggs are laid and incubated by the female. The male takes this time off to molt.

Goldeneyes and mergansers are less choosy with their nesting sites, and will include rock openings, abandoned buildings, open tops of tree stumps, and nest boxes, as suitable sites. Cavities constructed by pileated woodpeckers apparently are preferred by Goldeneyes.

Bufflehead female at nest

As for conservation, Bufflehead numbers are not in decline despite 200,000 to 250,000 being shot each year in the United States and Canada by hunters. As long as deforestation is controlled, the species should continue to flourish and remain of “least concern” from a conservancy perspective. Who knows, maybe the Bufflehead will continue to adapt to using human-provided nesting boxes or convert to the more traditional nesting methods employed by other species of duck, if tree cavities become hard to find.