Attacked by Swans

Mute Swan

Photo Credit: Wikipedia

I was surprised recently to see two pairs of Mute Swans feeding on grass and submerged vegetation at Schollenberger Park, Petaluma, CA. They appeared to be partners and presumably were preparing to breed in March or April. As we passed them with two small dogs one of them, I assume the male, hissed loudly, straightened its neck, and moved in the direction of our pets. The next step, if we had not moved our dogs to one side, was that the bird would flap its wings and physically attack. These birds maybe graceful and beautiful, but their aggressive behavior is out of line with their appearance. As well as chasing pets and children, they physically injure and will sometimes kill other birds, such as waterfowl, and when nesting they are known to attack canoeists, kayakers, and boaters on jet skis.

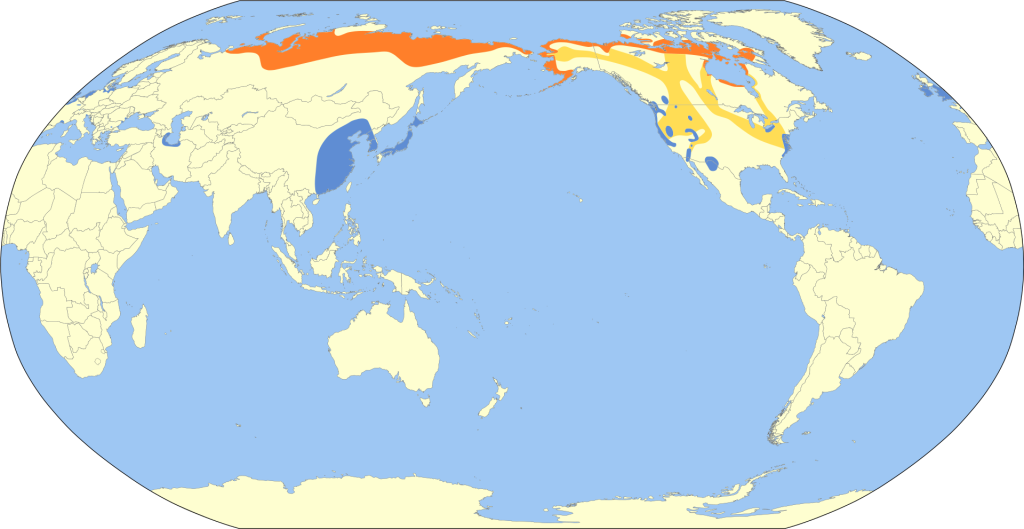

Swans are a non-native species to the United States and were introduced in the mid-1800s and early 1900s to adorn ornamental lakes, ponds, and city parks. Some went native and escaped to the wild, such as the ancestors of the four we discovered in Petaluma. Their preferred habitat is shallow coastal and fresh water such as estuaries, bays, waterways, streams, ponds, and lakes. Mute Swans are now distributed across North America, and their most significant populations are on the North Atlantic coast, across the Midwestern states, and into parts of the Northwest. There are smaller, localized populations in Canada and throughout the United States. These birds will migrate small distances, but generally do not wander far.

Mute Swan Range Map

Red – breeding habitat/resident; Blue – migration/winter area

Photo Credit: Wildfowl Photography

They are large birds, weighing up to 30 pounds (14 km), and are around five feet (150 cm) in length. The body of the adult is solid white. The distinguishing feature from other swan species is their orange bill, with its fleshy, black knob at the base of the upper bill. As described in my novel She Wore a Yellow Dress, my first experience with these birds was in England in the 1950s, when a pair would breed annually in a pond near my farm, and I would frequently visit their nest. I would dare myself to get as close as possible to the birds before the flapping and hissing of the male swan frightened me away. Today there are an estimated 7,000 to 16,000 breeding pairs in the UK. The species is native to much of Euro-Siberia where there are an approximate 500,000 birds, of which 350,000 are in Russia. They winter as far south as North Africa, the Near East, and northwest India and Korea. Mute Swans are not endangered and efforts to control their numbers are underway in some parts of their non-native territories.

They are not the only swan species I can see here in California.

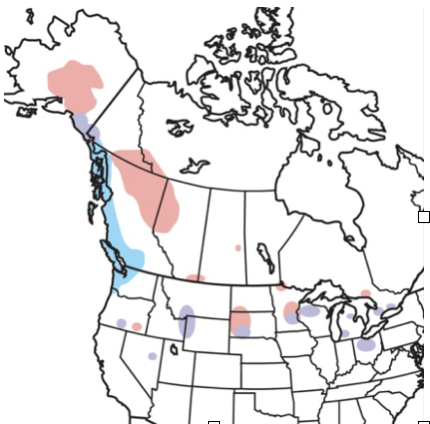

The most common species in North America is the Tundra Swan that usually makes its appearance in California from November to mid-March. They are North America’s most numerous swans, with a global population of around 280,000. They breed in the Canadian Arctic and coastal Alaska, on lakes, ponds, and pools that are near river deltas, and migrate to the Pacific Northwest, inland across to the Great Lakes, and as far as the coastal mid-Atlantic. The species is identified by its yellow patch at the base of its black bill. Sometimes it is referred to as the “Whistling Swan” because of the sound it makes with its wings in flight.

Tundra Swan

Photo Credit: Wikipedia

Tundra swans are also found in the UK and across northern Siberia to Japan. The British call it the Bewick’s Swan, the name that it was given in 1830 to recognize the work of the engraver Thomas Bewick, who specialized in illustrations of birds and animals. My sightings of this species have all been in California.

Tundra Swan Range Map

Orange – breeding; Yellow – migration; Blue – nonbreeding

Photo Credit: Wikipedia

Next there is the Trumpeter Swan, the one species that is native to North America, but rarely seen in California. Trumpeter Swans breed in northwestern Canada and Alaska and migrate to the Pacific Northwest. They can also be seen around the Great Lakes, and some migrate to the central interior of the United States. They are the only swans you are likely to see foraging in open fields. The bird is entirely white except for its black bill, legs, and feet. It has been spotted a couple of times in the UK, but I am still waiting to see my first one on either continent.

Trumpeter Swan

Photo Credit: All about Birds, The Cornell Lab

Trumpeter Swan Range Map

Purple- all seasons; pink – breeding; blue – winter (all regarded as uncommon)

Photo Credit: National Audubon Society

Finally there is the Whooper Swan, a species that is native to Eurasia, and a very rare vagrant to North America. A few birds from Siberia winter in small numbers in the Aleutian Islands, Alaska, but otherwise it is extremely rare. It can be identified by its fairly long, straight neck, black bill with a large triangular yellow patch, and a short tail. It is a species I have seen in the past. Back in the 1960s I saw the occasional Whooper Swan pass through Spurn Point in Yorkshire. It remains a winter migrant from Iceland to Britain, and about 16,000 birds appear annually.

Whooper Swan

Photo Credit: e-Bird

Whooper Swan Range Map

Orange – breeding; Blue – non-breeding

Photo Credit: Birds of the World

And as a postscript, who could prepare an article on swans and overlook the Australian Black Swan? This species is native to the south-east and south-west regions of Australia and is the official emblem of Western Australia. For Europeans, it is a bird that in history could never exist. It fell into the same category as “flying pigs”. Now, most fortunately, Black Swans have become a highly popular ornamental water bird in countries such as Japan, China, the UK, the United States, and New Zealand. The last time I saw this species was on an ornamental pond outside a hotel on the island of Kauai. Enjoy your swan watching.

Photo Credit: e-Bird