The bullfinch and the fruit trees

Female and male bullfinch

There was a small apple orchard close to our farm in the early 1950s that was one of my preferred childhood patches for bird watching. I would go there to watch jackdaws, woodpeckers, starlings, blackbirds, and thrushes, but during spring, I would see some rather stocky and colorful songbirds, often pecking away at the fruit blossom. They were called bullfinches, and if I saw a male, I would usually see the female close by. My stepfather used a shotgun to shoot them to protect our apples.

Back then, bullfinches were fairly common. According to a mid-1950s report published by the York Bootham School Natural History Club, bullfinch numbers had risen during the past 80 years in my part of Yorkshire, and remained a potential threat to commercial fruit growers. This threat was hardly new. In the 16th century, Henry VIII passed an Act of Parliament that paid one penny for every bullfinch killed.

Bullfinch in the window

Bullfinch in the window

In the 1970s their numbers declined and eventually the species was placed on the UK’s Red List of most threatened birds. Trapping and shooting of bullfinches is still permitted today, but a license to kill is required. Bullfinch numbers have become stable to slightly increasing, with about 190,000 breeding pair in the UK, although this still represents a third reduction since the mid-1960s. Culling is permitted today, but scaring and netting techniques are preferred to prevent the birds from causing damage to fruit trees. Currently the species is on the UK Amber Watch List of birds.

The male bullfinch is a strikingly beautiful and exotic looking bird, with a distinctive large black cap, blue-gray back, rose-red breast, a white rump, and thick bill. It is compact, about six inches (15 cm) in length. Females lack the flashy pink of the males, but are also attractive, with a pale brownish buff-colored breast and cheeks. They are very shy birds, although that has lessened in recent years as they have begun to appear at garden feeders. It is believed that individual bullfinches learn from other bullfinches and therefore it is hoped that this trend will continue.

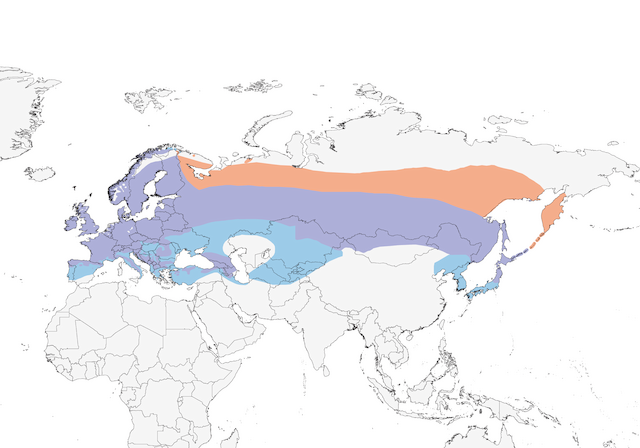

Bullfinches typically remain in the same area throughout their lives, although may move short distances during harsh winters. They build their nests in thickets of dense scrub and thorn, which is why I rarely found their eggs. They are often difficult to see because of their skulking behavior and preference to stay hidden in vegetation. The origin for their name is believed to be their plump-looking shape, although some speculate it is because they were once referred to as “bud finches”. They breed across Europe and temperate Asia, and are treated a woodland bird.

Bullfinch Range Map: orange – breeding; purple – year round; blue – non-breeding

Bullfinch Range Map: orange – breeding; purple – year round; blue – non-breeding

The bullfinch belongs to the Family of finches, even though it appears plumper and rounder than most other finches. In the UK, the most common finch I observed as an adolescent was the chaffinch. Although colorful, it is not as exotic looking as the bullfinch, although I did include it as the lead bird in chapter 20 of my novel She Wore a Yellow Dress.

Chaffinch – male

Chaffinch – male

Chaffinch – female

Chaffinch – female

Moving to California in 1979, I lost contact with both species of finch and have little opportunity to see them when I am back in England. Neither are present in North America, except for the occasional vagrant. Nonetheless, North America is home to 17 other species of these small to medium-sized birds, and includes the crossbills, grosbeaks, redpolls, and siskins, as well as those with finch in their title. One of the most common is the house finch, which looks similar to the linnet in Europe, and has an estimated North America population of around 31 million.

House finch

House finch

How these birds deal with climate change remains to be seen. There is evidence that some species are shifting their range due to rising temperatures and others, like the house finch, are nesting earlier.