When was the British Lapwing eaten as a countryside delicacy and why is it under threat today?

It was 1958, I was 14, and had recently joined the York Bootham School Natural History Club to broaden my knowledge of birds and to learn of the best birding spots near York. 138 species were listed by the School, and I had probably seen half of them. A description that caught my eye was that of the lapwing (also called the peewit or green plover) since this was one of the earliest birds I could recognize out in the fields. The Club’s report alarmed me by stating:

“Old Bootham records (beginning March 1851) indicate that this species has always been a common bird in the York area, but it is less common than it used to be. Many diaries at the turn of the century report the presence of many nests in fields near York, while today it is increasingly easy to find fields having no resident pair of breeding lapwing.”

It was enough to stop me from eating their eggs.

Lapwing nest and eggs

Lapwing nest and eggs

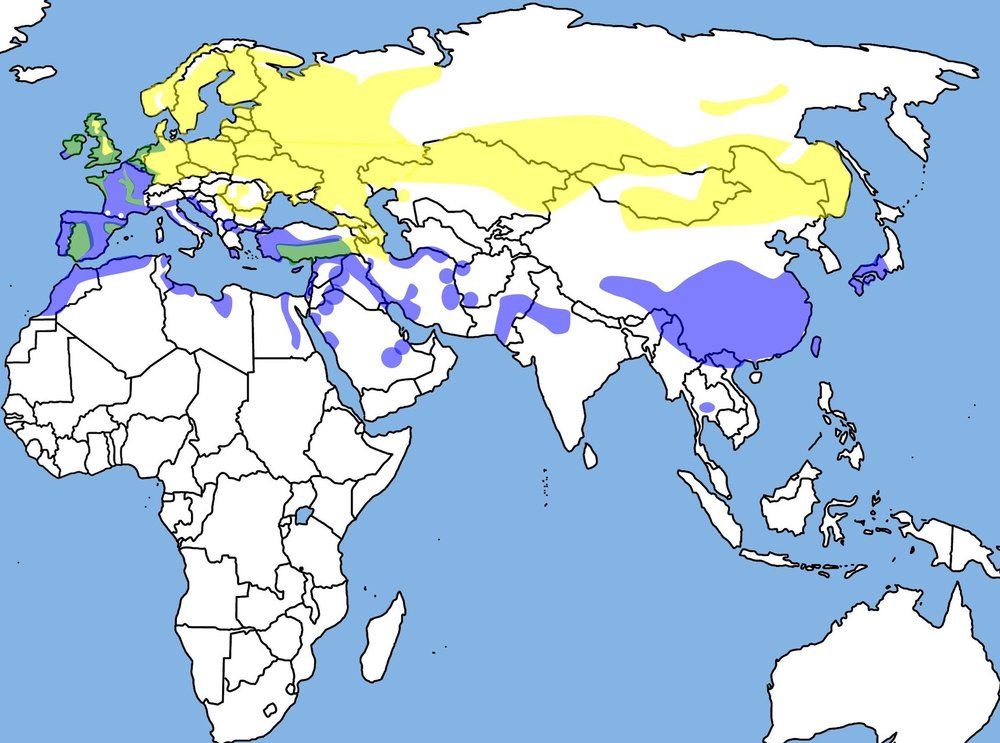

This pigeon-sized bird lays – usually 3 or 4 eggs – in an open field, using a scrape in the ground. If its nest is threatened, it may approach you and pretend a wing is damaged by dragging it along on the ground. If you do not follow, it may start to dive-bomb and screeching “peewit, peewit”. The bird is medium-sized (about12 in/30 cm) in length, has black and white plumage, a glossy green back, a wispy crest on its head, and rounded paddle-shaped wings. It breeds across northern Europe and north Asia, and winters as far south as North Africa, Northern India, and southern China. It gets its name from the undulating pattern of its flight and has long suffered from human activity.

Lapwing range map: yellow – breeding; green – year round; purple – winter

Lapwing range map: yellow – breeding; green – year round; purple – winter

Not only were lapwing eggs taken for food in earlier times, but the bird was killed and eaten as a countryside delicacy. The consequences became so severe that the British government passed the Protection of Lapwings Act in 1926 to make it illegal to offer the bird for human consumption or willfully disturb its nest. Even so, during World War 2, its eggs were knowingly taken and turned into powder to be consumed by soldiers on the front line.

This population decline has continued because of the use of pesticides, loss of habitat, and reduced food supplies. Their number in England and Wales is now approximately 80 percent lower than it was at the end of the 1950s. Even so, there are still an estimated 140,000 breeding pairs of lapwing, and in winter this number increases to around 650,000 individual birds because of visitors, with many gathering in flocks on flooded pastures and ploughed fields. The species is currently on the UK Red List of birds with conservation concerns, allowing for close monitoring and preventative actions.

Lapwings in winter

Lapwings in winter

I should mention that there is a similar looking bird in the southern hemisphere known as the southern lapwing. This species is widespread throughout South America and its range has expanded to Panama, Costa Rica, and other parts of Central America. Since its population is expanding, it is not considered at risk. Like the northern variety, it has a crest, can be very noisy, and makes use of similar habitats.

Southern lapwing

Southern lapwing

Arriving in California, I lost contact with this bold and beautifully crested bird They are not found in North America except for occasional vagrants in eastern Canada and the northeast US. Its closest relative in North America is the widespread killdeer which is also a member of the plover family, has similar feeding habits, is similarly rowdy, and feigns injury to protect its nest. This species I see during much of the year.

Californian killdeer

Californian killdeer

It seems a long time ago since I ate lapwing’s eggs, and regardless of its legality, I have no intentions of resuming the habit. Hopefully, steps being taken to safeguard the species presence in the UK will be successful. As temperatures rise, causing foreign birds to arrive in the UK, native birds such as the lapwing are at risk of being pushed out.

Cute lapwings

Cute lapwings