The American White Pelican

It is fall, and the time when many Californians catch sight of flocks of the white pelicans flying in formation between their breeding grounds in the northern interior of North America, to winter along the Pacific Coast as far as Mexico, on the Salton Sea, or around the estuary of the Colorado River. These heavyset birds majestically soar, hover, wheel and circle high overhead, before descending onto shallow water. They are the second-largest bird in North America (the California condor is #1), weigh up to 30 pounds, are nearly five feet in length, have a ten foot wing span, are dressed in stark white plumage with bold black markings under their wings, possess a massive bill, and carry their head in an S-shape during flight.

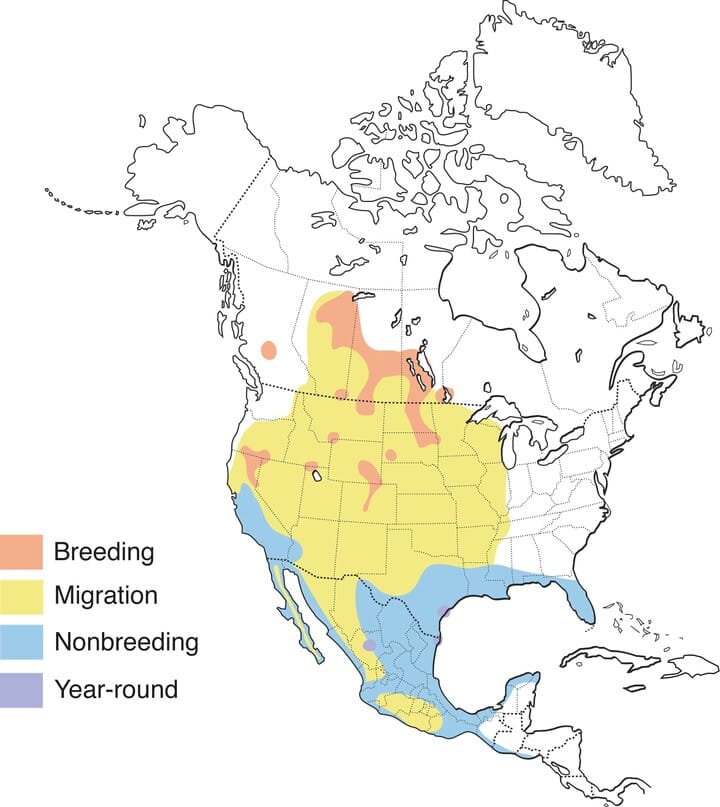

The ones that breed east of the Rocky Mountains usually migrate south and east along the Gulf of Mexico for winter, and those parenting west of the Rockies travel over deserts and mountains towards the Pacific Ocean. Populations breeding in Texas and Mexico usually winter there.

Migration is necessary to find new sources of food as their summer feeding grounds freeze-over. Their diet consists mostly of fish, especially small schooling fish such as chub, sticklebacks, mullet, and carp, and they forage during the daytime in winter, and at night while breeding.

American white pelican

American white pelicans nest in colonies on marshy or rocky islands close to, or on, remote freshwater mountain lakes, reservoirs and wetlands. It is estimated that there are about 60 breeding colonies in North America, and that each one can accommodate up to 5,000 birds. The largest ones exist in Utah, North Dakota, Minnesota, and in the inland states of Canada.

Global population ranges from approximately 140,000 to 180,000 individuals. Numbers fell dramatically during the mid-twentieth century due to hunting, the use of pesticides, and habitat loss, but have subsequently recovered. Even so, the species is threatened by environmental change, human disturbance, and retaliation from humans for preying on fish in commercial hatcheries.

The pelican’s nest is a depression on the ground or a mound of vegetation and dirt, usually containing one to three eggs. Only the strongest chick survives, with the others usually starving to death because they fail to compete for food. The bird’s life span is around 15 years.

Few sights are more captivating a flock of these large white birds circling overhead and then clumsily descending to the surface of the water either to forage for food or land on isolated islands for rest, to preen themselves, and to sleep. Probably the most visible feature of the American white pelican is its huge yellow-orange bill and distensible throat pouch. The bird is a dabbler, usually fishing in shallow waters less than six feet (180 cm) deep, by thrusting its large bill into the water to scoop up fish. A flock may sometimes work together to herd fish into shallow water where they are easier to catch. The flexible pouch acts as a fishing net to allow the bird to drain away the water and position the fish head-first before swallowing them. It is not used to store food.

The bird is similar in shape to the smaller and slender North American brown pelican, but the latter prefers saltwater rather than freshwater, and dives for its food rather than scooping up fish from the top of the water. It has gray-brown plumage, a yellow head, white neck, and the very distinctive long bill of all pelicans.

Brown pelican

They are mainly coastal birds, usually found within 5 miles (8 km) of sea, and are spread along the North America’s Atlantic and Pacific Coasts, most remaining resident in their territory.

Although it is not usual to confuse the American white pelican with other species of birds there are alternative large white birds in similar habitats that might cause confusion.

For example, snow geese, with their white plumage and black wing tips. They are much smaller than pelicans, and their bills are shorter and colored pink with dark edgings. They may be seen in huge numbers, honking in “V” formation flocks during winter as they migrate from their Arctic breeding grounds to the warmer parts of North America. They fly with their necks extended, and unlike pelicans, flap their wings constantly.

There are also all-white swans, such as trumpeter swans, that may be confused with the white pelican. These graceful, long necked, heavy-bodied birds glide majestically on the water and fly with slow, purposeful wing beats, and with necks outstretched. Last, there is the great white egret, an elegant bird, with a long, pointed yellow bill and black stilt-like legs, but unlike the pelican it stalks and spears its prey.

Trumpeter swan

Great white egret

During my early years of birdwatching in the UK, I never saw a pelican except in captivity. They had become extinct in Britain hundreds of years earlier during Roman times, when they were hunted for food and their habitat drained. According to fossil evidence, the pelican was common among Britain’s reed beds 12,000 years ago.

The species closest to Britain is the Dalmatian pelican that breeds in Eastern Europe around the Black Sea, and in parts of central Asia and Russia. It displays a stunning silvery-white plumage that contrasts with its orange-red pouch during the breeding season. On its nape it has a thick crest of feathers. You can imagine the excitement, therefore, among bird watchers when, a few years ago, a Dalmatian pelican was spotted near Land’s End in Cornwall, England. Presumably it had been blown off course.

Dalmatian pelican

And finally, the symbolism attached to the pelican in Europe is worth mentioning. Ancient legend has it that in times of famine a mother pelican would wound herself by striking her breast to feed her young with her own blood. The Christian faith took this myth to signify the death of Jesus Christ and the sacrifice of his own life for the redemption of humans. The bird thus became popular as an image on altar frontals and in stained glass church windows, as depicted below.

Pie Pelicane, Jesu Domine: Me immundum munda tuo Sanguine

(“Lord Jesus, Good Pelican: Wash my filthiness and clean me with Your Blood”)

Thomas Aquinas, 1225-1274.

Finally, as for their ability to deal with climate change, their summer range is forecast to shift northwards but wintering grounds may not be as flexible.