Phalaropes and their unusual sexual dimorphism

Red-necked phalarope

Sexual dimorphism was not something that had significance to me during my juvenile years as a bird watcher. I sometimes wondered why the female blackbirds were brown and why it was more difficult to identify female chaffinches and bullfinches than their more colorful mates. Probably the clearest example of this distinction was the pheasant, with the male’s rich chestnut and golden brown body contrasted with the female’s rather dowdy pale brown and black plumage. Of about 10,300 species of bird globally, virtually all are either monomorphic or sexually dimorphic where the male is the more brightly colored. I had yet to encounter the phalaropes, a variety of shorebird, that contradict the usual sex role. The female possesses the more brightly colored plumage, does not incubate the eggs, and may breed with multiple mates (polyandry).

The male chaffinch

The male chaffinch

The female chaffinch

The female chaffinch

My mother told me how male birds needed to compete to attract their mates and were the dominant partner during breeding. I was not convinced. When I looked at humans it was the female that wore the colorful clothing and ornamentation. Later on at Hull University, where I studied Geography, I learned that there are many cultures around the world where it is the male that wears the flamboyant clothing. I describe my years at Hull in the early chapters of my novel She Wore a Yellow Dress.

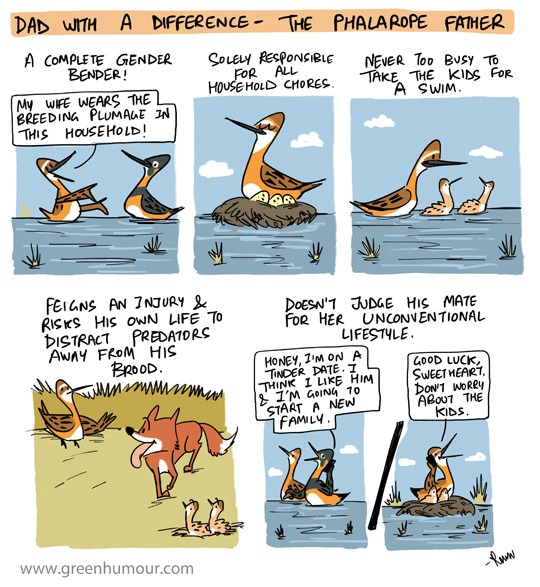

It was not until I moved to California that I came across phalaropes and witnessed reverse sexual dimorphism for the first time. There are three species of phalarope, all of which display this phenomenon, and the one I most typically see is the red-necked variety. Females are the more brightly colored bird and it is they that select their male partner. After the female chooses the nesting site, the male builds the nest, incubates the eggs, and nurtures the offspring, while the female goes off and may mate with other males.

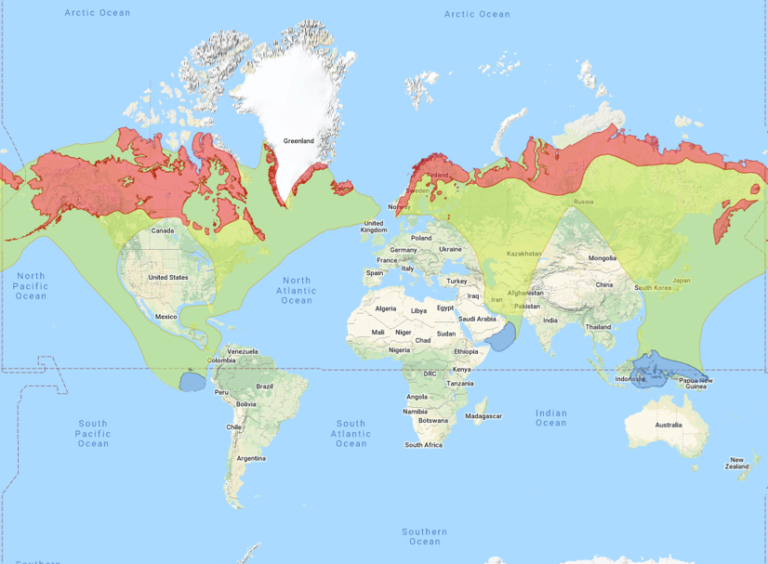

Red-necked phalarope Range Map: pink – breeding; green – migration; blue – winter.

Red-necked phalarope Range Map: pink – breeding; green – migration; blue – winter.

The red-necked phalarope and grey phalarope (or red phalarope as it is called in North America) are found both in Europe and North America, whereas the Wilson’s phalarope is restricted to the Americas. It is named after a Scottish-American ornithologist. These are small, delicate-looking waders, ranging in length from about seven inches (18 cm) for the red-necked phalarope, to up to nine inches (23 cm) for the larger Wilson’s phalarope.

Red phalarope, breeding female

Red phalarope, breeding female

Red phalarope, non-breeding adult

Red phalarope, non-breeding adult

Back in my early days, I hoped to spot either a red-necked or gray phalarope at Spurn Point during the 1960s visits but was unsuccessful. Both species are quite rare. The red-necked phalarope breeds in the UK, but no more than about 30 pairs, and these are located primarily in the western and northern Isles of Scotland. During fall, additional birds from Iceland, the Faroes and Scandinavia pass down the east coast, and it was one of these I had hoped to see. Some travel south-westward to migrate across the Atlantic and eventually arrive in the tropical parts of the Pacific Ocean off the coast of Ecuador and the Galapagos Islands, a journey of up to 6,200 miles (10,000 km). There they are joined by North American birds. Other European red-necked phalaropes turn south-east, and travel about 3,700 miles (6,000 km) to spend winter on the Arabian Sea in the Indian Ocean.

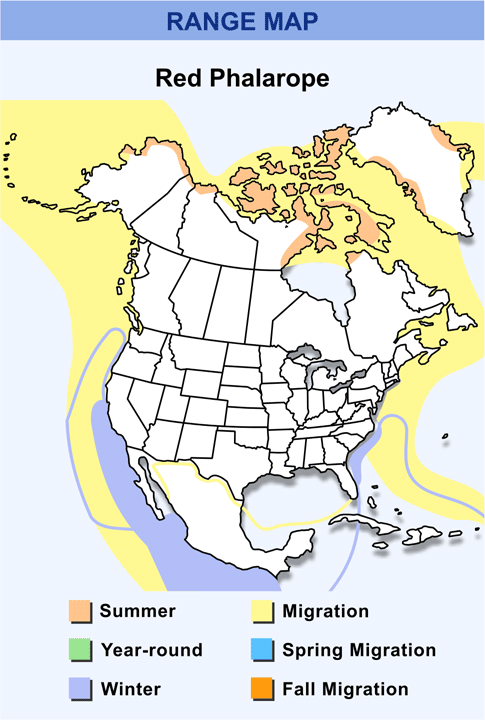

Red phalarope Range Map

Red phalarope Range Map

Gray phalaropes are an Arctic-breeding bird and are much rarer in the UK than the red-necked phalarope. They only migrate over the sea and their appearance on land is usually caused by birds being blown off course by storms. There are around 200 sightings per year in the UK. Gray phalaropes spend winter on the open sea off the west coast of South Africa. In North America, this species is known as the red phalarope, and breeds in the northern region of the continent, and for winter, they travel to the southern parts of the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans.

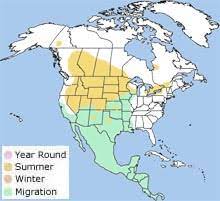

Wilson’s phalarope image and Wilson’s phalarope Range Map

Wilson’s phalarope image and Wilson’s phalarope Range Map

Wilson’s phalaropes nest in the north-west United States and Canada and migrate for winter along the west side of the continent to South America They move in large flocks and use a series of stopovers at places like the Great Salt Lake, Mono Lake, and the Salton Sea, as well as at sewage ponds and smaller wetlands. Like the other species, they spin to stir up their food and eat so much on stopovers that they can double their body weight.

Flock of Wilson’s phalaropes over Mono Lake

Flock of Wilson’s phalaropes over Mono Lake

Estimates are that there are around 4 million red-necked phalaropes worldwide, about 2.2 million red/gray phalaropes, and a global breeding population of 1.5 individual birds for Wilson’s phalarope. They maintain sufficient numbers that they are of low conservation concern. The exception is the red-necked variety in the UK where global warming is pushing its breeding territory northwards and the bird has not bred in Northern Ireland since 1980. Its conservation status in Britain is red. It also suffers population declines in places like eastern Canada where the loss of prairie wetlands has affected its numbers. Similarly, Wilson’s phalarope that nests in freshwater marshes sufferS from the drainage of wetlands.

The origin of the birds’ name is unclear; it maybe French. Phalaropes are strikingly beautiful and delicate-looking birds, with strong-willed females!