Download as PDF

5. Early Revelations

Several weeks later, back in Novato, California, Hilda was increasingly apprehensive about whether or not the woman in the Land Register would fulfill her commitment. Six weeks had passed, and the lady promised a reply within four. An irritated Hilda was drafting a letter to remind the woman of her pledge when the package arrived. It was a large, bulky envelope containing several official-looking documents. Everything was in German and Hilda understood none of it. Her neighbor, who read and spoke German, took charge of the cover letter, while a doctor friend called Bill, living in nearby Larkspur, agreed to translate the legal contracts. The remaining pages were converted into English by Hilda using her computer. She anxiously hoped that the correspondence would reveal details about her family’s ownership and describe the circumstances under which the building was lost during 1936. The letter confirmed the address of the building she visited as Guntzelstrasse 44, at the corner of Holsteinische Strasse 19.

The cover letter was signed by the woman Hilda talked to in the District Court and was quickly translated by the neighbor. It explained that the materials in the Register of Deeds confirmed Hilda’s family owned the property from 1919 to 1936. It showed her grandfather taking possession during June 1919, but unfortunately the handwritten document describing the transaction was written in a German script known as “sutterlin” and was impossible to read.

Maybe that didn’t matter. The 1919 purchase price was expressed in German Papiermarks, a currency discontinued in late 1923 because of German hyperinflation following the First World War. When the property was registered, there were thirty-three Papiermarks to the United States dollar, but four years later, the German currency was worthless. One trillion marks equaled a single dollar and a new currency had to be introduced a year later, with an exchange rate of one billion Papiermarks to one Reichsmark. The importance of the document

was to confirm the date of family ownership rather than to discover the property’s value at the time.

Hilda now knew the apartment building she visited in Berlin was her ancestral home, and had been the family source of income for seventeen years. Other correspondence among the papers she received implied her grandparents might have occupied the property for a longer period of time. There was evidence they lived at the same address as early as 1908, not long after the property was constructed. Hilda’s interpretation was the family must have been well-off and possessed the resources to give both their daughters untroubled and carefree lives.

There were two additional ownership deeds, one dated 1933 and the other 1936. Each was lengthy, and Hilda waited for Bill to complete his translations. The November 1933 document included a copy of her grandfather’s death certificate. She learned he died during December 1929, and his two daughters and wife inherited the building in accordance with German inheritance law.

German estate regulations required property to pass to next-of-kin immediately after death, with proportionate shares compulsorily assigned. Hilda’s grandmother received a quarter ownership and her grandmother’s two daughters each inherited three-eighths. In effect, Hilda’s mother, as an eleven-year-old, suddenly became the heir to a significant portion of the family business. The arrangement was certified in a 1933 ownership document, and the value of the building was recorded as 150,000 Reichsmark (U.S. $60,000). It was unclear whether the appraisal was at the date of death or on the day of certification. As a result, each daughter owned property worth 56,250 Reichsmark (U.S. $22,500), or an estimated half million dollars in today’s value.

The third deed, dated March 31, 1936, was the most alarming. It recorded the conveyancing of the property to a new owner. The person’s name was given and he carried the prefix of Hauptmann or Captain. It was unclear if the title referred to his status in the military or simply acknowledged him as the “head man” of his family. A more disturbing aspect was that the building had been declared “Aufgelassen” or “Abandoned” in the Registry of Deeds. Hilda wondered what this meant. There was no explanation. She speculated it was possible her family had been forced out of their home by anti-Semitism, and the property confiscated. As she solved one mystery, others seemed to emerge. There were no signatures on the last document, leaving Hilda to wonder if the transaction had been voluntary.

The same document showed the sale price for the property was 208,000 Reichsmark (U.S. $84,000), but the financial arrangements were complex and unusual. A 90,000 Reichsmark (U.S. $36,000) mortgage apparently existed that was assumed by the purchaser. Hilda always understood the family owned the property outright and did not need to borrow money. There was no explanation of why, when, and how this loan had been obtained. Another 78,000 Reichsmark (U.S. $31,500) was to be paid to Hilda’s grandmother and two daughters, presumably immediately, although there was nothing in the documents to confirm it was actually paid.

The biggest surprise was the third component. An amount of 40,000 Reichsmark (U.S. $16,000) was set aside to be paid as a delayed purchase mortgage. This meant the purchaser was not required to release the funds until, at the earliest, April 1941. During the five-year deferral period, quarterly interest payments were due at an annual interest rate of five percent. This seemed a strange arrangement, especially if the family was considering leaving Germany at the time of the sale. Before the due date for this payment, war would have begun, Hilda’s grandmother had died, and Hilda’s mother and father fled to Shanghai. It was incomprehensible that the family would accept such an arrangement. Maybe they had no choice. Was the money ever paid or did it remain an outstanding debt? Did the family of the 1936 purchaser still own the property? Were there bank records that would show payments had been made?

It seemed a series of new questions had arisen and the task Hilda set for herself was now much more complex. It was difficult to decide what to do next. If the research was continued, she might unearth family secrets that were embarrassing or shocking. She talked to John and other friends, and they told her she should continue. Maybe she would discover details of the purchaser, establish the chronology of ownership after 1936, and possibly investigate if proceeds from the sale were actually received by her family.

She wrote to her cousin in London to tell her what she had begun and heard back that the cousin’s mother often spoke of the 1936 purchaser as a person strongly disliked by the family. Hilda’s aunt had passed away in 1992.

Eventually, Hilda decided she was not going to give up. She would investigate the background of the 1936 purchaser, write to the lady in the Land Register requesting ownership records after 1936, and see what more she could learn about the circumstances of the sale.

Yellowhammer nest

Yellowhammer nest Yellowhammer range map

Yellowhammer range map

Lapwing nest and eggs

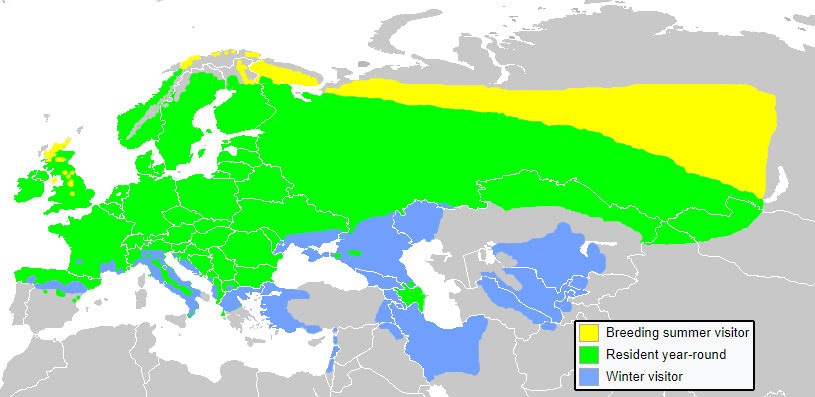

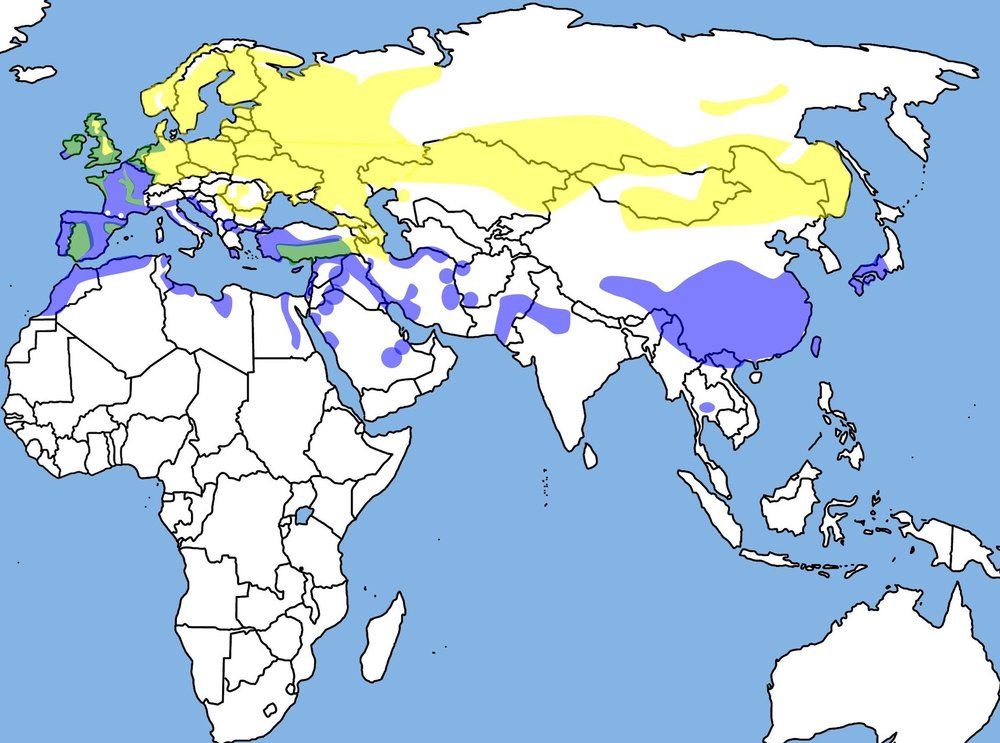

Lapwing nest and eggs Lapwing range map: yellow – breeding; green – year round; purple – winter

Lapwing range map: yellow – breeding; green – year round; purple – winter Lapwings in winter

Lapwings in winter Southern lapwing

Southern lapwing Californian killdeer

Californian killdeer Cute lapwings

Cute lapwings

Bempton Cliffs

Bempton Cliffs Gannets at Bempton

Gannets at Bempton Fulmar tubenose

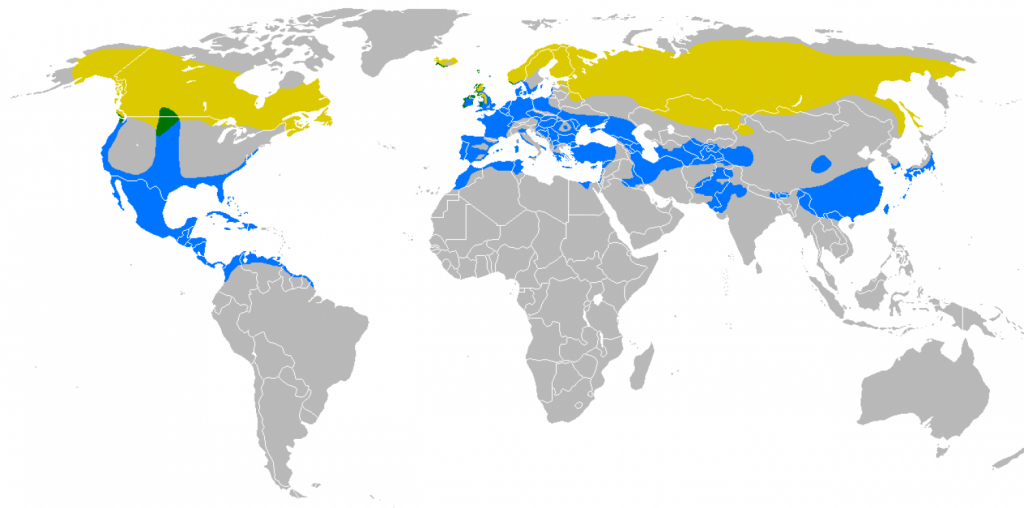

Fulmar tubenose Fulmar range map: yellow – breeding; blue – wintering

Fulmar range map: yellow – breeding; blue – wintering Pacific dark morph fulmar

Pacific dark morph fulmar

European kestrel

European kestrel Sparrow hawk

Sparrow hawk Merlin eggs

Merlin eggs